© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Wellington, New Zealand

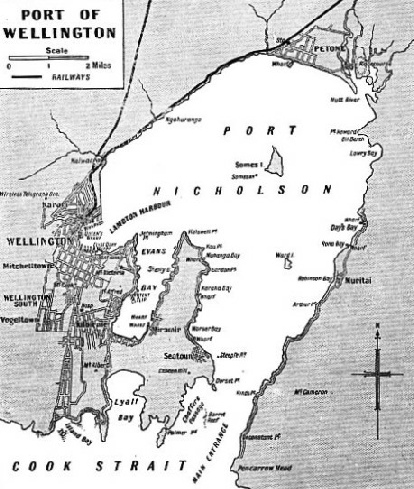

Although Auckland, in North Island, is the largest city in New Zealand, Wellington, also in North Island, is the capital of the Dominion and the chief transhipment port. The harbour of Wellington, set in magnificent scenery, is called Port Nicholson

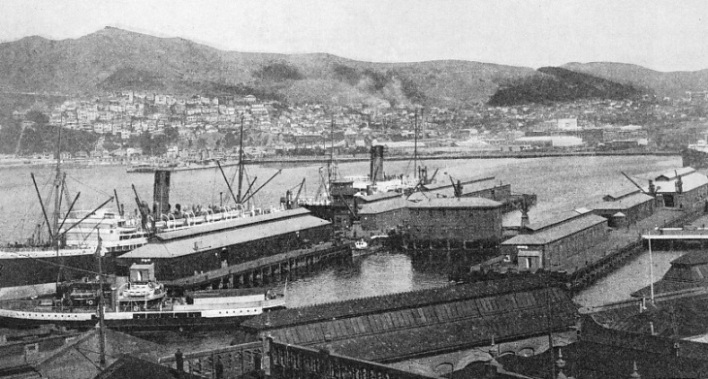

LAMBTON HARBOUR, PORT NICHOLSON, the wharves, known as the City Wharves, have a total berthage of 20,999 feet. At their berths there are usually one or two of the Union Steamship Company’s well-

THE magnificent harbour of Wellington, New Zealand, is called Port Nicholson. On the western shore stands the city of Wellington. The harbour is 20,000 acres in area, well sheltered and roomy enough for a fleet. It has an ample depth of water with good holding ground, and is almost half-

In less than a century Wellington has grown from nothing to be the chief port and the capital city of New Zealand, although Auckland, which is 547 nautical miles and 426 statute miles to the north, has a larger population and closely approaches Wellington as a port for handling cargo. The tonnage of cargo handled in 1934 was 1,705,831 tons at Wellington compared with 1,624,070 tons at Auckland. Wellington is the main port nearest to Sydney, Australia, and to Panama. The Panama Canal shortens the route to Liverpool by 1,564 miles compared with the Suez Canal route.

Wellington lies at the southern end of North Island, on Cook Strait, which separates North Island from South Island. It is this central position that makes Wellington the chief transhipment port, as a variety of ships distribute overseas cargoes to smaller ports in either island and also collect produce.

Although Wellington is about 12,000 miles from Great Britain, or about four times the distance of New York from Southampton, this remoteness emphasizes the efficiency of modern ships and the clockwork regularity with which the vessels on the regular lines are operated. Much of the excellent New Zealand mutton, butter, cheese and fruit which reaches the dining-

New Zealand has been developed as a vast dairy farm, orchard and sheep-

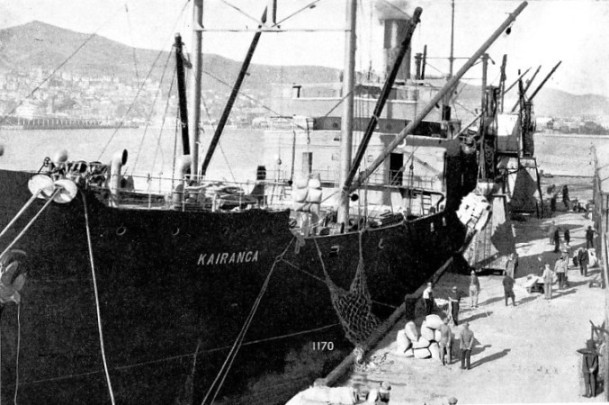

CARGO IS DISCHARGED AT WELLINGTON at the rate of more than 1,000 tons a day from many vessels. Wool, frozen meat, cheese and butter are the most important exports of New Zealand. Goods are brought to Wellington, the chief transhipment port, and transferred to ocean-

There are four sea routes to Wellington from Great Britain. The most direct of these is through the Panama Canal, the distance from Plymouth to Wellington being 11,063 nautical miles. The way out in the opposite direction through the Suez Canal and touching at Australian ports is 12,213 miles. Another route is eastbound round the Cape of Good Hope, 12,852 miles. The westbound route round Cape Horn is 11,969 miles. The first two routes are popular with travellers wishing to make the round trip entirely by sea.

For those who wish to see something of Canada or of the United States, shipping and railway companies provide routes across the Atlantic to New York, Boston, Quebec, Montreal and other ports, whence the traveller is carried by train either to Vancouver, British Columbia, or to San Francisco. He embarks at Vancouver for Auckland via Honolulu and Suva, or at San Francisco for Wellington via Tahiti and Raratonga. Alternatively he may go to Singapore and Java and then to Auckland and Wellington, but this route is a wide detour and not direct.

Famous New Zealand Ships

In its connexions with New Zealand the Shaw, Savill and Albion Line is the senior company linking with Great Britain, and its services go back to the days of sail. The steamships, ranging from 11,000 to 15,000 tons, load cargo in London, embark passengers at Southampton and proceed to Wellington and Auckland through the Panama Canal. Typical ships are the Tainui, 9,965 tons gross; the Tamaroa, 12,405 tons; the Mataroa, 12,390 tons, and the Akaroa, 15,128 tons.

The New Zealand Shipping Company has steamships and motor vessels of from 11,000 to 17,000 tons gross. The Rangitiki, 16,698 tons, is a motor mail liner and her sisters are the Rangitata, 16,737 tons, and the Rangitane, 16,712 tons. The oil-

The service from Vancouver to Auckland is maintained by the Royal Mail motorship Aorangi, 17,491 tons gross, and by the R.M.S. Niagara, 13,415 tons gross, of the Canadian Australian Line. From Auckland these ships steam to Sydney, so passengers take the train at Auckland to Wellington. The direct service to Wellington was maintained, until modified, from San Francisco by the two mail steamships of the Union Line, the Makura, 8,075 tons gross, and the Maunganui, 7,527 tons gross, both burning oil fuel.

Although the fame of these two vessels has not penetrated to the western world they are noteworthy ships in the remote islands of the Pacific. They called at Tahiti and at the British island of Raratonga on the run of 6,082 miles to Wellington. After Wellington they went to Sydney and there turned round. The runs were arranged so that the ship from San Francisco reached Papeete, the little port of the French island of Tahiti, with the mails on one Saturday every month, while the ship from Wellington arrived on the following Monday to collect mails. Therefore, all the British and Americans and French residents of Tahiti gathered at the post office on the Saturday morning eager for their letters. They would spend the week-

The run from San Francisco to Wellington is not so long as that from Panama, which is 6,500 miles. The Port Line (Commonwealth and Dominion Line) runs services direct from London via Panama, with such ships as the motor vessel Port Dunedin, 7,441 tons gross, and the steamship Port Hunter, 8,430 tons gross.

Hundreds of Acres Reclaimed

Approaching Wellington from across the mighty Pacific is an unforgettable experience. Even in these days of motor and steam vessels the huge expanse of ocean and the awesome loneliness of the tumbling unfenced sea-

Presently the liner turns to starboard and enters Cook Strait, which divides the two main islands. Taourakira Head is passed, then Baring Head upon which a new lighthouse, with a light visible for twenty-

Presently the liner turns to starboard and enters Cook Strait, which divides the two main islands. Taourakira Head is passed, then Baring Head upon which a new lighthouse, with a light visible for twenty-

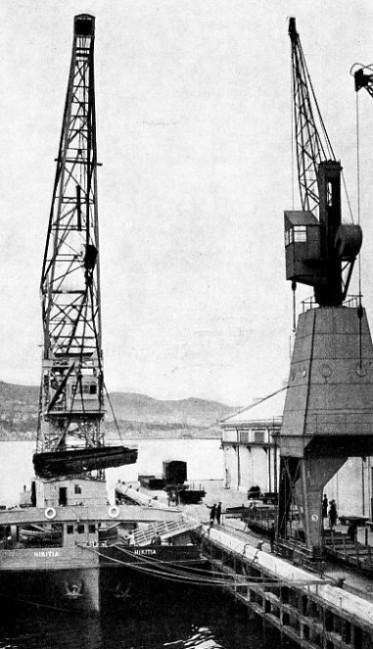

A FLOATING STEAM CRANE with a lifting capacity of 80 tons is owned by the Wellington Harbour Board. For legal purposes the crane is registered as a ship, with the name of Hikitia. She has twin screws and was built at Paisley, Refrewshire, in 1926. She has a length of 160 ft. 1 in., a beam of 52 ft. 3 in. and a depth of 11 ft. 3 in.

After the long voyage across the tropics the air of Wellington is refreshingly cool, and the business and efficiency of the city smarten up the wanderer who has come from the lazy islands of Polynesia or the easy-

Level land is precious in Wellington, where all roads lead uphill, so that from the beginning the harbour engineers have steadily reclaimed land from the sea, amounting to hundreds of acres, to gain room for quays and buildings.

Because of the risk of earthquakes there are no skyscrapers in the city. The buildings, however, are spacious and attractive, the best being the Houses of Parliament, built of New Zealand marble, fronting a lovely lawn and backed by green hills. The sea-

In his ramblings round Wellington, whether he walks or takes a tram, a motorcar or a motor-

H.M.S. Hood, for instance, was tied up at Pipitea Wharf, the outermost of the City Wharves, where the maximum depth alongside is 46 feet. This battle cruiser of 42,100 tons displacement, with a length of 861 feet, a beam of 105 feet and a draught of 31 ft. 6 in., was berthed without any fuss. She is by no means the deepest draught ship to be berthed at this wharf. The draught record is held by the whaling factory vessel Kosmos, which draws 36 feet aft and has a gross tonnage of 17,801. She berthed with her whale chasers alongside as if they were chicks nestling against a mother hen. She and other factory ships, such as the Sir James Clark Ross, and the C. A. Larsen, use Wellington as a fitting-

It seems surprising that the harbour and the hills were absolutely bare less than a century ago. Elsewhere in New Zealand the name of Captain Cook is thrust upon one. The great navigator, however, did not survey this expansive harbour. On his first voyage he missed the entrance. On his second voyage he took a peep at it, but the wind came fair for his departure and he went away without having made an adequate survey.

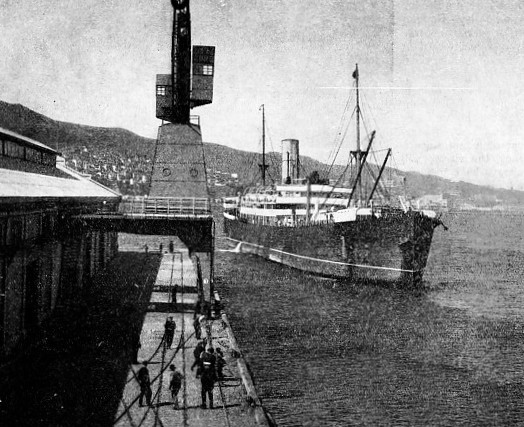

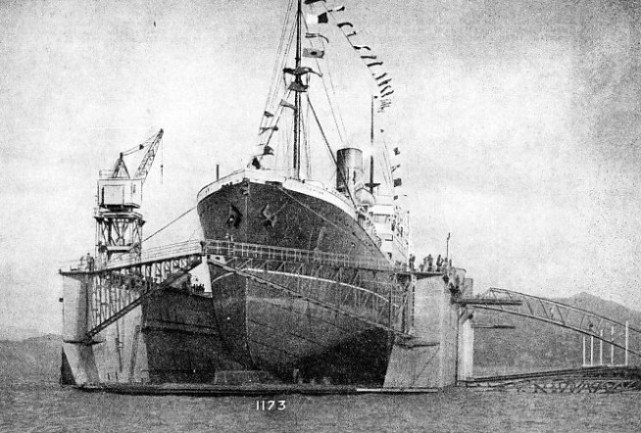

AN IMMIGRANT SHIP arrives at Wellington. The Ruapehu, which was named the Australasian for a short period, was built at Dumbarton in 1901. A vessel of 7,885 tons gross, she had a length of 457 ft. 3 in., a beam of 58 ft. 2 in. and a depth of 30 ft. 9 in. She belonged to the New Zealand Shipping Company

For more than half a century no other ship approached the inlet. In 1826 it was visited by two British ships, the Rosanna, Captain James Herd, and the Lambion, Captain Barnett. Captain Herd gave the inlet the name of Port Nicholson out of respect for Captain John Nicholson, of the Royal Navy, who had been his friend and benefactor. The name of Captain Barnett’s ship was bestowed upon the harbour which is the water-

Until 1935 the entrance light was on Pencarrow Head. The light was 322 feet above high water and was obscured in thick weather, so another light was placed below it on a rock 32 feet above the sea and called the Lowlight. This side of the entrance rises up to Mount Cameron, 827 feet. The western side of the entrance is not so high. It consists of a wedge-

Between the two shores of the entrance is Barret Reef, which divides the channel. The main entrance, which is between the reef and Pencarrow, is used by large vessels. Small craft sometimes use the other channel, Chaffers Passage, which is between the reef and the western shore. From shore to shore the entrance, at its narrowest part, is over 3,600 feet wide, and the deep-

Ward Island is an islet just past the entrance where the bay opens out, and two miles beyond this is a larger island, Somes Island, which is the quarantine station, almost in the middle of the bay. The Hutt River flows into the northeastern corner of the bay, and the shore line swings round to the westward, where it forms a bend comprising Lambton Harbour. It drops to the south and then north in the shape of a narrow U, forming Evans Bay, and finally dips south again to Palmer Head and the entrance.

Ward Island is an islet just past the entrance where the bay opens out, and two miles beyond this is a larger island, Somes Island, which is the quarantine station, almost in the middle of the bay. The Hutt River flows into the northeastern corner of the bay, and the shore line swings round to the westward, where it forms a bend comprising Lambton Harbour. It drops to the south and then north in the shape of a narrow U, forming Evans Bay, and finally dips south again to Palmer Head and the entrance.

WELLINGTON HARBOUR known as Port Nicholson, has a water area of 20,000 acres. The city of Wellington lies on its western shore and the main wharves are situated in Lambton Harbour and Evans Bay. The city’s ocean front lies to the south on Cook Strait. Somes Island, in the centre of the harbour, serves as the quarantine station.

The bight formed by Evans Bay is nearly met by another running inland from the sea and called Lyall Bay. The two bays are separated by a low spit of land. Lyall Bay and Island Bay, farther west, form part of the ocean front for the citizens of Wellington. Electric trams link the city with the suburbs, some of which are on the ocean front.

17,000-

In addition to the City Wharves, in Lambton Harbour, which have a total berthage of 20,999 feet, there are the Suburban Wharves, total berthage 4,305 feet, in other bays in Port Nicholson.

The City Wharves cover more than two and three-

The biggest crane in Wellington is the floating steam crane Hikitia, which lifts 80 tons. Next in capacity is a 35-

A feature of the port method of dealing with transhipment and other goods is the use of tractors and trailers, for the uninterrupted lay-

Cold storage is an important feature and the building can hold 35,000 crates of cheese and 65,000 cases of apples. Cheese and fruit arriving by rail is brought to one side of the store and unloaded and stored, and on the other side coastal vessels unload similar produce, which is stored until the overseas ship arrives.

With such a slight tidal range, dock gates are not necessary. Small ships requiring attention are hauled up on two patent slips situated in Evans Bay, the larger of which can take vessels up to 300 feet in length and the smaller vessels up to 170 feet.

TESTING WELLINGTON’S FLOATING DOCK in April 1932. The Ruahine, representing a weight of 11,200 tons, was docked successfully and without a hitch. The dock has a length of 533 feet over the keel blocks and a clear width of 87 feet between fenders. The dock was towed from Great Britain to New Zealand. The Ruahine, 10,870 tons gross, has a length of 480 ft. 7 in., a beam of 60 ft. 3 in. and a depth of 41 ft. 1 in. She belongs to the New Zealand Shipping Company.

Beyond Lambton Harbour is the floating dock which can raise vessels of 17,000 tons. This great structure was towed in 1931 from the Tyne to Wellington with a crew of eleven men, in 166 days (see page 1051). It was tested at Wellington in April 1932, when the Ruahine, representing a weight of 11,200 tons, was docked. The overall length over keel blocks is 533 feet, and the clear width between fenders 87 feet.

This dock, with the patent slips, enables every class of ship repair to be done at the port, and there is also plant for repairing marine engines of all types. A powerful tug, the Toia, 422 tons gross, 135 feet long and 29 feet in beam, has a speed of over 12 knots, and is in readiness for salvage or fire-

In their care of the big ships the Harbour Board has not overlooked yachts and motor-

The transhipment trade of the port is most important. Coasting vessels and swift passenger ships act as feeders to the ocean liners and ships on the inter-

In 1930 the Wellington Harbour Board celebrated its fifty years’ jubilee. The story of the port begins in 1839, when the ship Tory arrived with Colonel Edward Gibbon Wakefield to select the site of the colony to be founded by the New Zealand Company. Within three years 340 vessels arrived, including what are known as the “first ships”, the Cuba, Aurora, Oriental, Duke of Roxburgh, Bengal Merchant, Glenbervie, Bolton and Adelaide, 640 tons, which was the largest of them.

Early Steamship Services

Ships formerly anchored offshore and discharged into lighters which brought the goods to private Wharves, but this system ended in 1862, when a beginning was made with Queen’s Wharf alongside which ships could berth.

There was no regular steamship service to Great Britain. Mails were taken to Melbourne and carried thence by P. and O. ships to Singapore, whence the Indian Mail Service took the mails to Suez. Here they were carried overland to Egypt and transhipped, for this was before the Suez Canal was cut. To solve the problem the Panama, Australian and New Zealand Royal Mail Company started a service from Sydney and New Zealand across the Pacific to Panama, whence the mails were taken by railway to the Atlantic side and shipped to Europe.

When this service ceased the Australian Steam Navigation Company started a service with the City of Melbourne and the Wonga Wonga from Sydney. These ships picked up the mails at Wellington and ran to San Francisco, but the distance was too great for these small, early steamships. Then the Californian, New Zealand and Australian Steam Packet Line put on three wooden paddle steamers, the Nebraska, Nevada and Dakota, to carry the mails up to Honolulu, where they were transferred to the Moses Taylor and taken to San Francisco; but again the long run ended the venture.

The Australian and American Steamship Company was the next to try and to fail; but the Pacific Mail Steamship Company took up the service in 1876 and kept it for ten years, after which it was taken over by the Oceanic Steamship Company in conjunction with the Union Steamship Company. Since 1909 the mails from Wellington to San Francisco have been carried by the latter company.

The love of the sea is strong among all classes of New Zealanders. Boat and yacht sailing is practised more in the Dominion than in most other countries. Most of the land is rugged, so that sea transport of goods and passengers is often more convenient than land transport. In addition, the opportunities for taking part in yachting or sea fishing are numerous. Wellington is a long way from the homeland, but this lovely and flourishing city by the sea is a living monument to British maritime enterprise.

QUEEN’S WHARF, IN LAMBTON HARBOUR, is the centre of shipping activity in Wellington. The first quay was built in 1862, and it has been greatly extended. Queen’s Wharf is one of the ten City Wharves, which cover nearly three miles of water-

You can read more on “The Empress of Britain”, “Floating Docks” and “Great Ports of the World” on this website.