© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

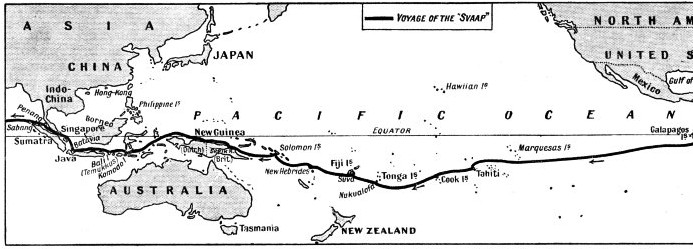

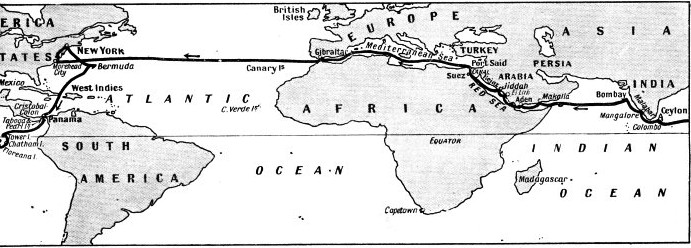

Voyage of the “Svaap”

Having learnt navigation in a public library, a young American, William Albert Robinson, sailed round the world from New York between June 1928 and November 1931 in a ketch only 32 feet 6 inches long overall

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

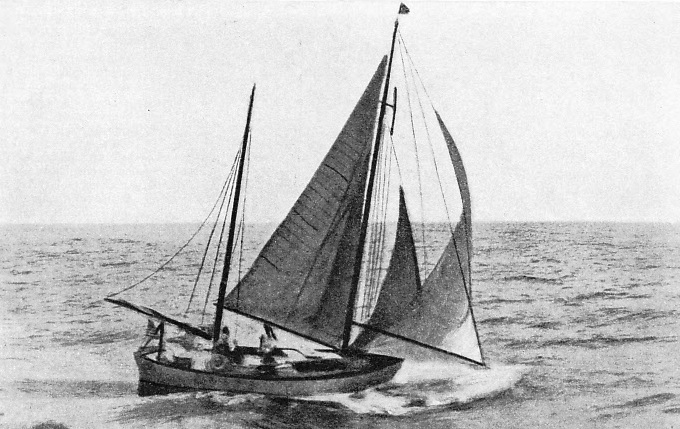

THE KETCH THAT CIRCUMNAVIGATED THE GLOBE, Robinson’s Svaap, was bought second-

NONE of the circumnavigators in small yachts has done better than a young American named William Albert Robinson, who sailed from New York on June 23, 1928, and returned three and a half years later. Robinson did not sail alone, but always had at least one companion, the most remarkable of his shipmates being a Tahitian named Etera, who joined him at Tahiti and stayed with him until the end of the voyage.

Robinson is the outstanding example of the younger generation of blue-

In addition to mastering the engine, Robinson kept his boat beautifully. At Gibraltar, when the Svaap had sailed thousands of miles and had only the last leg to do before completing the round-

A VOYAGE OF THREE AND A HALF YEARS was in store for Robinson when he set out from New York on June 23, 1928, to sail round the world. Some friends accompanied him on the first leg of the voyage, which was from New York to Bermuda through the hurricane area. The Svaap was slightly damaged in the Gatun Locks of the Panama Canal and was overhauled on the beach of one of the islands guarding the Pacific side of the canal. Robinson then crossed the Pacific to New Guinea by way of the Galapagos, Tahiti, the Cook Islands, Fiji Islands, New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. In New Guinea Robinson explored the interior for some months. The course was now to the Dutch East Indies, including Java, where Etera was delivered from jail after having given trouble to the Dutch authorities Then the Svaap sailed to Singapore, Colombo (Ceylon) and Mangalore (Southern India). After the crossing of the Indian Ocean, Robinson had adventures with pirates in the Red Sea. The passage of the Mediterranean from Port Said to Gibraltar was hampered by the pranks of Etera. From Gibraltar the Svaap sailed to Tenerife, Canary Islands, and thence via Morehead City (North Carolina) to New York reached on November 24, 1931. The Svaap had made six passages each exceeding 1,000 nautical miles.

Robinson pays due tribute to Etera, but Robinson was the captain. He mastered his boat, he mastered his engine and he mastered Etera. This last was the most remarkable feat of all. A few men could have achieved the first two, but it took a man of Robinson’s gifts to achieve the third. Most men would have become positively disgusted with Etera ashore, and some might have been tempted to push him overboard at sea and blame the weather when they reached port; but Robinson found Etera a congenial companion.

Robinson started out when he was twenty-

The Svaap was a ketch designed by a famous American designer, John Alden of Boston, and was built in 1925 in Nova Scotia, so that she was not new when Robinson sailed from New York. She had a length of 32 ft. 6 in. overall and of 27 ft. 6 in. on the water-

A few minor alterations were made to suit Robinson’s ideas, as the ketch was designed for offshore cruising and not for the whole of the ocean. He slightly reduced the height of the two masts, replaced the tiller with a wheel, removed the cockpit at Tahiti and replaced it with an after cabin which provided quarters for Etera.

The sail area when the Svaap was in ocean cruising trim was about 560 square feet, and the sails were jib-

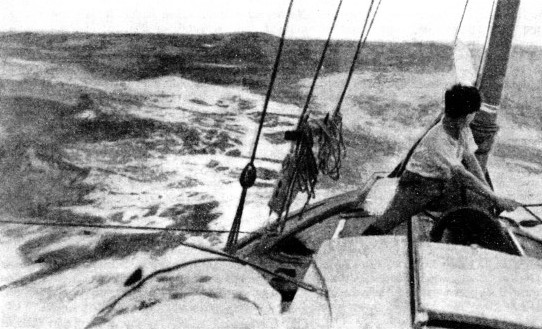

Always striving to get the most out of his yacht, and as keen on sailing during the last leg of the voyage as on the first, Robinson achieved some excellent daily runs, once logging 190 miles from noon to noon and more than 175 miles on a number of days. On an ocean passage to get an average speed of between 7 and 8 knots for twenty-

On the first part of the voyage, from New York to the Panama Canal, the Svaap ran the gauntlet of the hurricane area, as Robinson sailed in June 1928. Robinson set out with some friends who had agreed to sail as far as Bermuda, and before she reached there the Svaap had to ride to a sea-

BEFORE THE NORTH-

In Gatun Locks the Svaap went through the usual ordeal by water and the ketch bucked as a bronco does. She gave her bowsprit a nasty jar, but emerged intact except for a dent in the port bulwark. Ships are towed through the locks by electric locomotives, but small yachts such as the Svaap are too small for this and are so low in the water that the lines let down from the lock are almost perpendicular.

In every instance the men have only one set of lines and do not lead them from both sides of the lock, so that they have no purchase on the yacht when she is plunging about in the grip of the water which boils up from the great intakes. It cost Robinson only £2 10s. to pass the yacht through the canal, and £1 of this was the fee for measuring the yacht.

He and Bill beached the yacht at Taboga, one of the islands that guard the Pacific side of the canal. On this island they painted and overhauled her and made a squaresail. Then the Svaap sailed a few miles to the Pearl Islands, where Robinson exchanged the San Blas dug-

The stretch of sea between Panama and the Galapagos is remarkable for calms, squalls and cold weather, the coldness being due to the Humboldt Current which comes up from the Antarctic. Robinson, therefore, had to wrap himself up in heavy clothes and even a blanket as he sailed towards the Equator. He became weary of trying to get his southing to make Chatham Island and altered course to one of the northerly islands, Tower Island. Where Robinson differs from some circumnavigators is in his great interest in Nature. He has a zest for sailing into little-

The islands have so far defeated man. No inhabitants were found there when they were discovered by the Spanish, and attempts to colonize them have always failed. Some of the strangest creatures in Nature live on the group, and the sea teems with great fish which can turn the tables on man. Ashore, Robinson found his right of way disputed by a sea-

Robinson landed on several islands, including Chatham Island, where he obtained stores and water, and Floreana, where he took on board dried fish and fruit from one of the survivors of a Norwegian colony. Then he left for a non-

Tahiti was reached in thirty-

Safely Through a Hurricane

Robinson was making preparations to sail, but found difficulty in getting a man as crew until he located Etera and asked him how long it would take him to get ready to sail round the world. Etera said “Five minutes”, and was engaged.

During the first part of the voyage with Etera as crew the Tahitian was on relatively good behaviour in the South Sea Islands. At sea he soon proved his value.

In the Cook Islands Robinson carried mails and two native passengers, one of whom was terrified when Robinson drove the yacht hard in a blow. When the Svaap was in the Tonga Islands there came warning of a hurricane, and Robinson and Etera rode it out anchored with several other vessels off Nukualofa. During the hurricane the wind was so terrible that Robinson could not stand on deck, and had to use all his strength to stay on deck lying flat. But the yacht emerged intact after the hurricane had passed.

The Svaap was a lucky little ship. She came off a slip at Suva, Fiji, where she was overhauled, and two days later a larger vessel on the slip was broken up by a tornado. Robinson had sailed from the harbour and the tornado missed the Svaap. In the New Hebrides, the Solomons and New Guinea, Robinson enjoyed his contacts with the savage islanders. He stayed in malarial places but avoided fever, pinning his faith to quinine and keeping his bunk screened from mosquitoes at night.

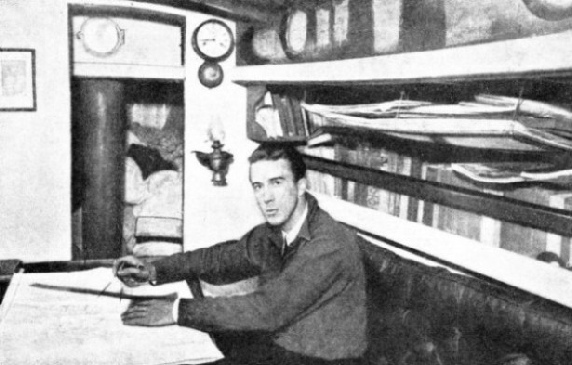

IN THE MAIN CABIN OF THE SVAAP were berths, transom seats, a folding table and 200 books. Under the berths and seats were lockers. Abaft the cabin was a galley, with a swinging oil-

Sailing on towards New Guinea, Robinson had many adventures and met strange people, not all of them coloured. Etera caused trouble at one place where the missionaries had plantations by telling the natives that the secular plantation owners paid 10s. a month, whereas the mission people paid only 3d. a week. The bishop and some of his clergy asked Robinson to confine Etera to the yacht as he was putting wrong ideas into the heads of their converts.

Etera lost heart on the voyage along the north coast of New Guinea, as he thought they were getting to the end of the earth where there were neither white men nor Polynesians. He made himself ill with worry. Robinson called in the aid of a doctor at the next white settlement, and the doctor cured Etera of his fears by giving him a bottle of eucalyptus oil to rub into the limbs in which he complained of pains.

When Etera had recovered his nerve, Robinson left him to mind the yacht while he made a trip up the Sepik River in the yacht of the Administrator of the Mandated Territory. When Robinson returned to the Svaap he sailed her to a settlement in Dutch New Guinea, only to find that the town had been given up by the white men. He had been out of touch with civilization for more than six months, and had expected to find banks and stores in the town.

The next settlement was 436 miles away, and Robinson started on the passage with only 11s. 2d. On the way he met some fishermen and bartered tobacco and matches for fish and coconuts. At last he reached the settlement.

To his surprise the German who was the leader of the three traders had an anti-

At last the Svaap struggled clear of fickle winds and currents and cleared the end of New Guinea with her crew of two living on yams, fish and biscuits. They had a stroke of good fortune when they arrived at a place with a Dutch Resident who arranged credit for Robinson with the Chinese traders; but soon after this they were down to one spoon and one fork for cutlery. The tin-

On the island of Komodo Robinson shot a wild boar, which Etera cooked in the South Sea style. He dug a hole, built a fire and made stones red hot, then raked out the ashes and wrapped the boar and the vegetables in leaves and placed them on the hot stones. The oven was then earthed in and the meal left to cook. This method is the best for an island feast, and the two men ate a gigantic meal.

Robinson left Etera in charge of the yacht at Temukkus, in the north of the island of Bali, while he went to the south of the island for a few weeks. Robinson enjoyed his visit to the wonderful haven of native art, and returned to find trouble. Etera had run up bills all over the town, had been on one long carouse and had disappeared. Robinson searched the island in vain and engaged a cross-

The yacht was overhauled, and a few weeks later was about to sail for Batavia when the Java police told Robinson that Etera had been found hiding in the mountains of Bali. He had been captured and shipped to Java, where they were keeping him in jail until Robinson was ready to put to sea, when they would deliver the erring one on board. This was the beginning of Robinson’s troubles with Etera. At sea he was as good as gold, but in port he was as bad as bad can be. He had the gift of being able to get drink without paying for it in countries where he could not speak the language, and it was his undoing ashore. At Singapore, when Robinson announced his intention of getting to Europe by way of the Red Sea, he was warned that the Arabs would try to capture the Svaap, and well-

He sailed to Sabang, off the north end of Sumatra, laid in stores for the passage of a thousand miles to Colombo, and made a splendid run across in a week, blowing before the monsoon under mainsail and a small spinnaker. The beggars of Ceylon spoiled his enjoyment, and he soon sailed to the Malabar Coast of India, intending to go up to Bombay. Because of the lateness of the season he changed his plan and decided to make the most of the north-

As the water he took aboard at Mangalore was doubtful, he chlorinated it profusely so that it was safe but unpleasant. A shortage of funds limited him to stores worth only £2 10s. for the ocean crossing. He experienced light airs in the Indian Ocean, and the food had to be rationed. He saved the petrol to the end of the voyage, and had to use the engine for the last stage, reaching Mokalla, Arabia, with the food almost all eaten.

As he hurried ashore, Robinson walked into danger. A Mohammedan festival had worked up to its climax, and the wandering infidel from the sea was menaced by a sword-

Imprisoned By Arabs

At a place called El Lith, the yachtsman was captured and taken ashore to a fortress where he was imprisoned.

He was allowed back to the yacht to get some important papers, and he succeeded in bluffing his captors with the impressive seals on these documents. The seals were contrived by the aid of the stopper of a bottle of eau-

At the Mediterranean ports Etera recovered his spirits and his thirst, and defeated all Robinson’s efforts to keep him sober. At last the uncertain Mediterranean was left behind as the Svaap sailed out of Gibraltar for the Atlantic crossing. She reached Tenerife in eight days, and Robinson prepared for the last ocean passage. He bailed Etera out of jail a day too soon, as the Tahitian began another carouse when Robinson was ready to sail, but Robinson captured him when he returned to the yacht for a hat, and held him prisoner long enough to get the yacht under way. The run of 4,000 miles from the Canary Islands to Morehead City (North Carolina) was made in thirty-

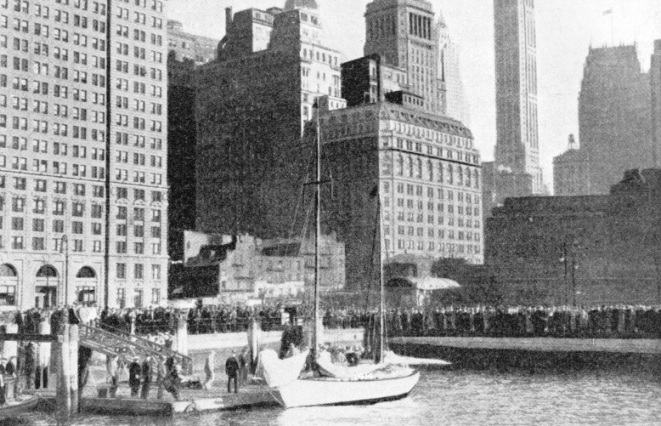

AT THE END OF THE WORLD VOYAGE, spectators welcoming Robinson on his arrival at New York in November 1931. From Tenerife, Canary Islands, the run of 4,000 miles to Morehead City (North Carolina) was made in thirty-

You can read more on “Captain Slocum the Pioneer”, “The First Voyage Round the World” and “Pidgeon and the Islander” on this website.