© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Singapore: Crossroads of the East

Apart from its importance as one of the world’s great ports, Singapore is particularly interesting because its commerce is set amid the glamour of the East. Formerly a haunt of Oriental pirates, Singapore is now a centre for picturesque native craft and fishermen who work by most unusual methods

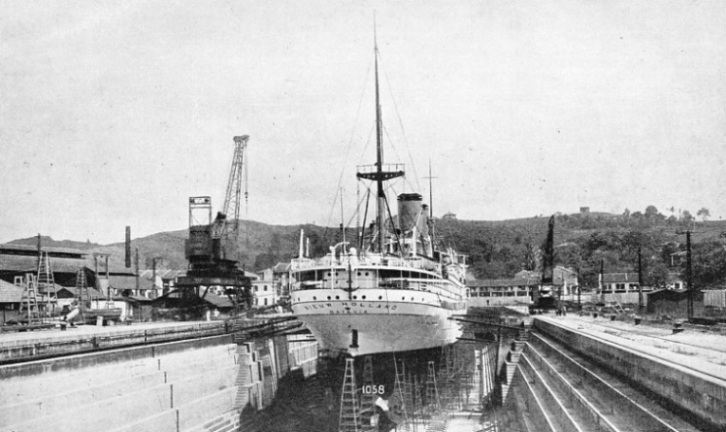

IN KING’S DOCK, SINGAPORE, the Nieuw Holland is undergoing examination. The King’s Dock is 879 feet long, 100 feet wide at the entrance, and has a depth of 34 feet on the sill at high water ordinary spring tides. The Nieuw Holland is a Dutch twin-

SINGAPORE is one of the key ports of world trade because of its situation at the southern extremity of Asia. It is a nerve centre of ocean trade routes and it is also a port of transhipment for the produce of southeastern Asia, including the Dutch East Indies, Siam, French Indo-

Almost landlocked by islands, Singapore Harbour, which is one of the most beautiful in the world, is so well protected that many vessels discharge and load without going alongside the wharves. Lighters convey the cargo to and from warehouses on the banks of the Singapore River, which threads its way through the city, and to and from warehouses at one of the basins.

The depth of water enables ships of more than 40,000 tons to go alongside the main wharf. The rise and fall of ordinary spring tides is only 9 feet, and therefore the docks and basins are available at all stages of the tide, excepting the dry docks, which are entered through the usual gates.

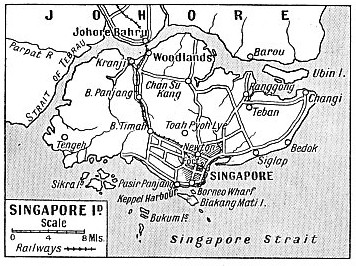

Singapore is the name of the entire island as well as that of the port and city. The port is on the southern shore. A narrow channel called the Tebrau Strait separates the island from the mainland of the Malay Peninsula. The Strait is bridged by the Johore Causeway, which carries a road and a railway.

The total area of Singapore and the small islands belonging to it is 217 square miles. It lies at the south-

South of Singapore, which is less than a degree and a half north of the Equator, is a chain of islands and islets extending eastward from the coast of Sumatra.

THE ISLAND OF SINGAPORE is separated from the Malay Peninsula by the Tebrau Strait, which is bridged by the Johore Causeway. The Singapore Strait separates the island from the north coast of Sumatra. The port of Singapore is on the south coast of Singapore Island.

The long peninsula of Malaya materially affects the ocean routes of the Orient. Vessels using the Suez Canal and trading between Mediterranean ports and ports on the same latitude in Japan and China have to go almost to the Equator. They have to steam farther south than ships proceeding from ports on the same latitude as the Mediterranean and bound from the Atlantic to the Pacific Coasts of North America, as the Panama Canal is about nine degrees north of the Equator. Below Singapore the long island of Sumatra extends to six degrees south of the line, where the Sunda Strait separates Sumatra from the island of Java. This is an even less convenient route for ships trading between the Far East and Europe.

The development of steamships, the Suez Canal and the rise of Japan and China as industrial countries are among the chief causes of the growth and importance of Singapore as a world port. The opening up of the commerce of the great islands which lie south, east and west of Singapore and the enterprise of the traders of the port have developed a vast transhipment trade which has gained for Singapore the title of “Crossroads of the East”.

No ship passing from the Indian Ocean to the China Sea and the Pacific can pass north of Singapore, and the next gap in the long chain of islands that extends almost to Australia is several hundred miles away. So excellent are the shipping facilities which make Singapore a re-

Because of the multitude of small islands, islets and rocks, the vessels trading in these waters are small, handy ships able to thread their way through reef-

Except for the vision and enterprise of one man, Sir Stamford Raffles, who founded the modern port in 1819, Singapore would not exist. The site of the island was so important that centuries before his time a flourishing port arose to profit by trade between China, the East Indies and India, but the city was destroyed by the Javanese. The surviving Malays fled and founded Malacca, which attracted the Portuguese. They were the first Europeans in these waters, and they captured the port.

Then the Dutch took Malacca and were followed by the British. Malacca changed hands several times. It was during the period when Malacca had been ceded back to the Dutch that Raffles sought out the site for a new port which would command the traffic through the vital Strait of Malacca. He determined to establish a trading station which would break the Dutch monopoly, and he secured a lease from the local ruler. Raffles landed at the mouth of the little Singapore River and founded the modern city.

He made it a free port and almost immediately traders flocked to it. Malacca, now British, has declined to a small historic town, and Singapore has become what Raffles called it, “the emporium and pride of the East”. Strangely enough, Alexander Hamilton refused Singapore as a gift when it was offered to him by the Sultan of Johore in 1703, although Hamilton wrote that it was “so conveniently situated that all winds served shipping, both to go out and come in”.

This policy of free trade, in contrast to the restrictions imposed by the Dutch, also took away the trade of the Dutch port of Rhio, on an island in the Rhio Archipelago on the south side of Singapore Strait. It made Singapore the distributing centre for native produce and for manufactured goods landed by ships from Europe. Until the Indian Mutiny, in 1857, Singapore was part of the possessions of the East India Company. Afterwards the port passed to the Indian Government until it became a Crown Colony controlled by the Colonial Office.

When Raffles arrived in 1819, Singapore was notorious as a haunt of Malay pirates, and many years elapsed before these pests were stamped out. They did not use large craft but relied upon light boats which could be paddled swiftly to overtake a sailing ship in light winds. When a ship was becalmed the pirates swooped upon her and made off with their plunder to creeks and rivers too shallow for naval ships to enter.

Piracy Stamped Out

By these tactics the pirates were able to reach the jungle and hide before pursuit could be organized. On the introduction of steam, ships no longer lay immobile at the mercy of the pirates. A more effective patrol was maintained and piracy ceased.

About three-

They were anxious to benefit by British protection. Previously they had found a grave obstacle to credit business with Malay customers. When a Malay got into debt he sometimes considered the account settled by murdering his Chinese creditor. The British brought such murderers to book, and the laws were so firmly administered that the Chinese enjoyed more security than in their own country.

Even for an Eastern port Singapore is extraordinarily cosmopolitan. In addition to Chinese, Malays and British there are Indians — who are almost as numerous as the native Malays — Arabs, Japanese, Eurasians and various natives from the islands. When they travel by sea, the natives are deck passengers and take all their provisions and sometimes all their worldly goods with them.

Between 2,000 and 3,000 deck passengers can be packed on to the deck of one of the larger steamships which cater for this class of passenger. As Malays are Mohammedans, the ambition of every Malay is to make the pilgrimage to Mecca. As soon as he can acquire the fare he goes to Singapore and travels on the deck of a steamer to the Red Sea port of Jidda. Indians, Chinese and natives of the East Indies crowd the decks of ships taking them from Singapore to other ports.

SINGAPORE HARBOUR is always crowded with shipping of many types and nationalities. The Inner Harbour has an area of four square miles and the Outer Harbour and Western Anchorage bring the total area up to thirty-

The first steamship to reach Singapore arrived round the Cape of Good Hope in 1840, and the first P. and O. mail vessel in 1845. The docks were created by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company, which was formed in 1863. In 1905 the docks were taken over by the Government and placed under the control of the Singapore Harbour Board.

With an area of more than 36 square miles, the port consists of the Inner Harbour of 4 square miles, the Outer Harbour of 11·8 square miles, and the Western Anchorage of 20·4 square miles. A mole about a mile long protects the Inner Harbour from easterly winds blowing into the Singapore Strait and affords sheltered anchorage for about forty coasting vessels of from 150 to 300 feet in length. The mole also protects the water-

Numerous islands protect other parts of the harbour so effectively that at one time the berthing accommodation consisted of wooden wharves on wooden piles. Since then new wharves have been built and, in addition, much of the foreshore has been reclaimed and improved. At the western limits of the port, on various islands, are the oil tanks and storage facilities. This is the centre for shipping petroleum products to foreign countries. The quarantine station is at the southern approach to the port on West St. John’s Island. At the eastern end of the harbour land has been reclaimed from mud flats and there is a civil aerodrome to accommodate seaplanes as well as aeroplanes.

11,139 Feet of Wharves

The south side of the entrance to the the Singapore River is spanned by the Anderson Bridge and other bridges. The boat basin just inside the river is crowded by hundreds of sampans berthed alongside a boat quay. Passengers from ships anchored in the harbour are landed by launches at Johnston’s Pier, Collyer Quay.

Wharves and basins extend south from this point to the East Wharf, where the water-

This dock is designed to allow of its being deepened if need arise. It is adequate for most ships, as the draught of vessels going east from Europe is limited by the Suez Canal to 34 feet. Four wharves have between 25 and 30 feet of water alongside, and two have less than 25 feet of water.

As the port is so far from the industrial countries the repairing and dry-

OCEAN-

The European accustomed to the towering cranes and grabs of northern ports will not see many of these at Singapore, where the hard-

Coal is the only bulk cargo handled at the Harbour Board’s premises, and this is handled by coolies. The coolies work in pairs, and carry a basket containing 160 lb. of coal suspended from a bamboo pole, which rests on their shoulders. A coal-

There is a fleet of wooden lighters mostly of 50 tons capacity; also 100-

Pipe lines are laid to the wharves from palm oil and latex (rubber) bulking plants, and pipe lines supply diesel and fuel oil to vessels alongside the Main and West Wharves and the north and west walls of the Empire Dock.

Strange Delicacies

The general cargo handled is so varied that an extra wide space has to be allowed between the transit sheds and the edge of the wharves to enable cargo to be sorted and handled quickly. Peas arrive from India, Burma and China to be reshipped to Sumatra, and vermicelli and oil cakes from China are sent to the Dutch East Indies.

The strange delicacies which tempt the Chinese palate are represented by bêche-

Singapore is the chief distributing centre for petroleum products in Malaya, and is an important centre for the export of tin, which is smelted locally. The leading items in the re-

A large and varied fleet of coasting vessels is maintained by the Straits Steamship Company. The vessels range from small craft of less than 50 tons net register, designed to penetrate to up-

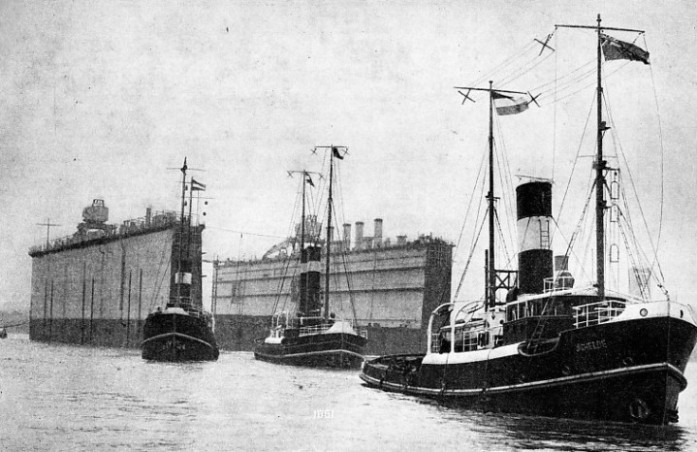

TOWED FROM ENGLAND TO THE STRAITS, a distance of 8,500 miles. The floating dock for the Naval Base at Singapore was built at Wallsend-

With associated companies comprising the Siam Steam Navigation Co., whose ships go to ports of Siam and the east coast of Malaya, the Sarawak Steamship Co., whose ships go to Sarawak, and the Hua Khiow Steamship Co., whose ships go to Muar. The ships of The Straits Steamship Company serve over a hundred ports. The ships serve the Strait of Malacca, go up the east coast of Malaya to Bangkok in Siam, up the west coast to Moulmein in Burma, and across the China Sea to British and Dutch Borneo and the South Philippines. They serve also the east coast of Sumatra. They touch at little ports of which the outside world has never heard, and thread their way through the mazes of archipelagos and reefs in these eastern waters.

Before the days of steam the trade of the port was seasonal according to the monsoon. The monsoon brought the Chinese junks with tea, raw silk, camphor and earthenware, and junks from Siam with sugar and rice. These ships loaded in Singapore their return cargoes and waited for the wind to change to blow them home. In 1933, 2,868 vessels of a total net register tonnage of 8,765,920 berthed in the port.

Fishing is an important local industry, and some of the methods are novel to Europeans, as the fisherman often goes into the sea after the fish. The Japanese are the most successful and supply nearly half the fish landed on the island, the remainder being caught by Malays and Chinese. Fish last only a few hours in the tropics and nearly all the fish are salted down in the fishing boats immediately they are caught.

Teams of Japanese swimmers drive fish into a net. First the net is fixed near a reef or rocks. The swimmers then enter the water in a crescent formation, the horns of which touch the reef. The men wear goggles so that they can see under the water and they drive the fish before them into a long bag net.

Ingenious Fish Traps

Malays and Chinese use fish traps made of bamboo, canes and palm leaves as well as nets. The traps are set in the tideway with winged screens to lead the fish into them. Other traps resemble lobster pots and are baited. An ingenious method is to anchor clusters of coco-

of leaves and slowly draw it towards their net so as not to frighten the fish which follow the food.

Owing to the enterprise of the Chinese Singapore has made progress as a manufacturing city. The majority of the canning factories are owned by Chinese. Machines crush copra, the dried kernel of the coco-

The Naval Base, which is an important part of the defences of the British Empire, is not available for merchant vessels It is on the Tebrau Strait between Singapore and the mainland.

One of the most notable features of the base is Dock IX, the floating dock which was towed some 8,500 miles from the River Tyne, England, to Singapore in 1928, and was officially opened in the following August. This, the third largest floating dock in the world, is 857 feet long and 126 feet wide, with a depth of 40 feet on the sill at high water. The dock can lift a battleship of 50,000 tons displacement out of the water.

You can read more on “The Empress of Britain”, “Floating Docks” and “Great Ports of the World” on this website.