© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve

Since its formation in 1903, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve has grown in importance as well as in numbers. A volunteer organization, with divisions in many parts of Great Britain, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve offers to the sea-

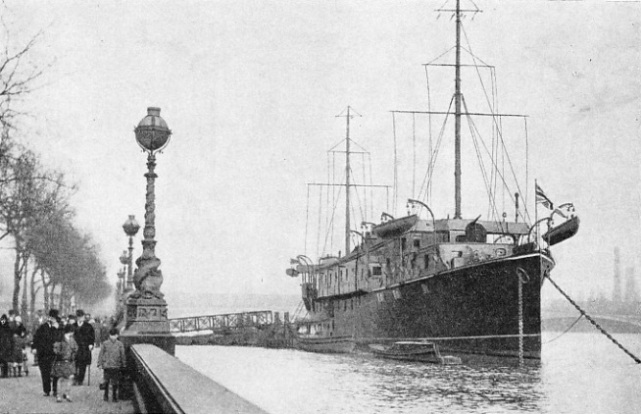

MOORED OFF THE THAMES EMBANKMENT above Blackfriars Bridge, H.M.S. President is the London training ship of the R.N.V.R. She was built in 1918 as H.M. Sloop Saxifrage, with a length of 262 feet, a beam of 35 feet, and a displacement of 1,290 tons. All Officers employed in the Admiralty are nominally appointed to H.M.S. President.

THERE are many British boys with salt water in their veins who would like nothing better than to make the sea their profession, but who are forced by circumstances to pursue their vocations ashore The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, the “Wavy Navy”, as it was affectionately called during the war of 1914-

The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve was founded in place of the Royal Naval Artillery Volunteers, which were established in the early ’seventies when there was every possibility of a naval war with Russia. Men came forward in considerable numbers for a time, but finally the R.N.A.V. was killed by official neglect. When it was gone its value was realized. In 1903 the R.N.V.R. was formed to take its place, beginning with divisions in London, the Clyde and the Mersey. To the surprise of Admiralty officials, there was an immediate response to the call by just the right kind of recruit.

At the time that the London Division of the R.N.V.R. was started there was a large proportion of yachtsmen in the ranks. These men could handle a boat in any circumstances and were familiar with the approaches to the capital. One company consisted entirely of Stock Exchange men. The new R.N.V.R. had some excellent commanding officers and real enthusiasts in the other ranks, so that when war broke out in 1914 the strength was more than 4,000 officers and men, and the individual quality extraordinarily high.

In the first months of war the naval service was well manned, but the Army was under establishment. A large proportion of the R.N.V.R. was incorporated into the Royal Naval Division for service ashore. Then the majority of the first contingent was sacrificed in an attempt to save Antwerp. Brigaded with the Royal Marines, these citizen sailors made a great name for themselves ashore in the Dardanelles and on the Western Front. During the war the numbers of the R.N.V.R. increased to about 32,000 ratings, apart from officers.

Efficient men found work in the big ships of the Grand Fleet. One man was selected to be Chief Yeoman of Signals in the Fleet Flagship, a wonderful compliment to an amateur in a job that is regarded as one of the most highly specialized in the Navy. A large number went into merchant ships as armed guards, and the various blockading units found infinite use for ratings in boarding parties.

The vessels of the Auxiliary Patrol were manned mainly by the R.N.V.R. A number of the men even found themselves in the trawlers and drifters which had been taken over. Armed yachts and motor-

The work done by the R.N.V.R during the war of 1914-

Such social organizations as the R.N.V.R. (Auxiliary Patrol) Club kept a big proportion of the officers who had served in the war in close touch with one another, and helped the authorities immensely in their plan. In 1921 the force was reorganized in the light of war experience. The status of qualified R.N.V.R. officers was established, especially their right of taking command with regular naval officers of .corresponding rank. These trained R.N.V.R. officers were also offered the opportunity of qualifying as specialists in various branches.

The London Division

Since this reorganization there have been many changes on economical and other grounds. Although some subdivisions have been closed down -

The London Division is based in H.M.S. President, which was built as the sloop Saxifrage in 1918. She was built at Clydebank and had a displacement of 1,290 tons. Her length was 262 feet and her breadth 35 feet. Her engines, with an indicated horse power of 2,500, gave the Saxifrage a speed of 17 knots. She had stowage for 260 tons of coal and was armed with two 4-

H.M.S President is moored off the Thames Embankment, and is used as the nominal ship of all the officers appointed to the Admiralty, from the First Sea Lord downwards. She has been partly roofed over and completely changed in appearance since she was built to fight submarines.

The name President has always been the traditional name of the London training ship, first of the R.N.R. and then of the R.N.V.R., for well over half a century; but as one species of the saxifrage is popularly known as London pride, it seems rather a pity the President could not have kept her old name. London has every reason to be proud of her civilian sailors.

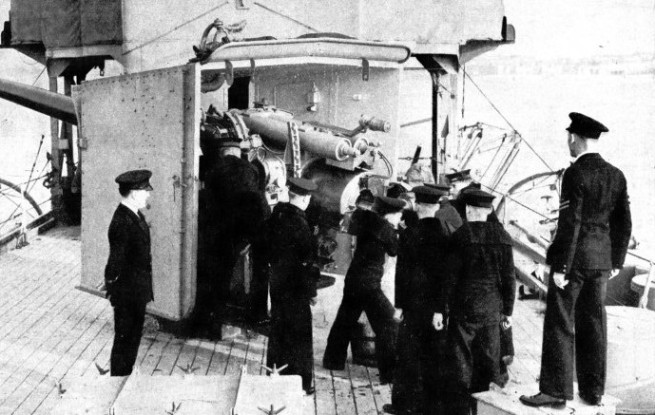

ON THEIR ANNUAL CRUISE, men of the R.N.V.R. go to sea in a warship and undergo important practical training. This photograph shows a party of men from H.M.S. President (London) at gun drill on board H.M.S. Curacoa. A cruiser of the Ceres class H.M.S. Curacoa, 4,290 tons displacement, carries five 6-

The Scottish Division was split into two in 1926. The Clyde Division had its headquarters ashore at Glasgow and the Greenock Sub-

The Severn Division has H.M.S. Flying Fox at Bristol and the Mersey Division has H.M.S. Eaglet in the Liverpool Docks and H.M.S. Irwell, removed from Manchester, at Birkenhead. The Sussex Division has no port facilities for a training ship and has to be content with a big drill shed at Hove as headquarters, with a sub-

The Tyne Division, which was founded in 1905, has the Satellite at North Shields, and the former cruiser Calliope, the famous “hurricane jumper” of Samoan fame, at Newcastle. The Calliope was the only warship that escaped from Apia Harbour, in Samoa, during a fierce hurricane in 1889. Every other warship in the harbour was wrecked.

The Ulster Division at Belfast is the youngest of all the divisions. Its formation was proposed by Sir James Craig (later Viscount Craigavon) in the summer of 1921, when he was the leader of the Ulster Party. Sir James Craig was interested in naval affairs after having been Financial Secretary to the Admiralty. This division has H.M.S. Caroline, one of the “C” class cruisers that did such excellent work in the North Sea during the war of 1914-

One of the most carefully planned features of the reorganization was the plan to make the Service appeal to the inland districts, as well as to the areas within reach of the various divisional headquarters. For this purpose officers were graded into List 1 and List 2. List 1 consists of officers who live near enough to headquarters to attend the ship for their regular evening drills and to take their place as divisional officers. List 2 comprises those living out of reach of headquarters, who do extra training to compensate for their absence from drills and divisions. It includes also most non-

The non-

Among the executive officers of the R.N.V.R., a large number are willing to go to great trouble to qualify as specialists in various branches. The courses of instruction take up a great amount of time and energy, and these executive officers spend many hours in the various headquarters and training ships.

Among the executive officers of the R.N.V.R., a large number are willing to go to great trouble to qualify as specialists in various branches. The courses of instruction take up a great amount of time and energy, and these executive officers spend many hours in the various headquarters and training ships.

PRACTICAL TRAINING IN SMALL BOATS forms part of the routine work of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. A boat is seen in this photograph leaving the pontoon alongside H.M.S. President. This branch of the R.N.V.R.’s activities is of particular interest to those volunteers who have had some experience of yachting.

The gunroom officers of the R.N.V.R. consist of midshipmen and sub-

The senior ranks range from two-

For promotion to petty officer, high qualifications are required. Genuine enthusiasm and enterprise are necessary and thus citizen petty officers can challenge comparison with the petty officers in the regular service. There is also a staff of regular naval Chief Petty Officers for instructional purposes. This appointment is made immediately after pensions are taken, and is much sought after in such branches as the physical training, signal gunnery or torpedo branches. Warrant rank is open to the best men in the seamen, signal and telegraphist branches.

The regulations lay down the minimum number of drills and the minimum amount of training which the rating must put in. In his first year he must attend forty drills and after that twenty-

physical training. Every headquarters or drill-

The drills are interesting and the headquarters or drill-

Voluntary Easter Cruise

In addition to the drills at headquarters, naval training is carried out in the ships of the fleet or in one of the home ports. Normally the obligatory period of training is fourteen days a year, but qualified ratings are allowed to volunteer for longer periods up to a maximum of three months. Two ratings for the Sussex Division were chosen for service in H.M.S. Renown when that battle cruiser carried T.R.H. the Duke and Duchess of York to Australia in 1927.

In addition to the regular fortnight, which can be arranged largely to suit the convenience of the volunteer, the London and Sussex Divisions of the R.N.V.R. offer a voluntary cruise at Easter for about 100 men.

There are generally about four times as many volunteers for this cruise as there are vacancies. When the Vice-

The R.N.V.R. movement has proved such a success in Great Britain that there are now branches in Canada, Australia. South Africa and New Zealand. There are fifteen headquarters of the Canadian Division of the R.N.V.R. The South African R.N.V.R. is based on Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth and East London. Nine bases serve the needs of the Australian Division, and the New Zealand Division has four. The authorities have also permitted the formation of smaller branches in Kenya, Hong Kong, Singapore and Colombo. Officers and men of the branches overseas are just as keen as those at home and are capable of doing the same excellent work.

In contrast to the practice of the British Army, in which all ranks on active service, whether Regulars, Militia (Special Reserve) or Territorials, wear undifferentiated badges of rank, the R.N.V.R. are distinctive. Some representative examples are illustrated in the colour plate accompanying the chapter “In the Royal Navy”.

SIGNALLING INSTRUCTION being given to men of the London and Sussex Divisions of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve on board H.M.S. Curacoa during the cruise in April, 1936. As many as 400 men often apply for the 100 vacancies which are available for this annual cruise. Instruction in every branch of training forms part of the routine on board.

You can read more on “In the Royal Navy”, “The Navy Goes to Work” and “The Royal Naval Reserve” on this website.