© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

In the Royal Navy

Before a youth may enter the Royal Navy he must pass through the long period of training and discipline necessary for those who would serve under the White Ensign

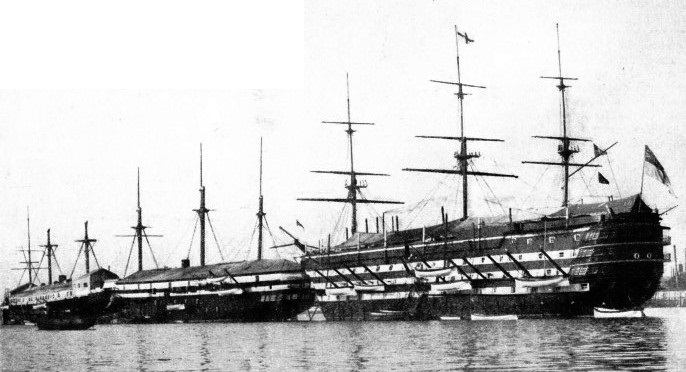

BOYS ON BOARD THE TRAINING SHIP WARSPITE, moored off Grays, Essex. This ship is controlled by the Marine Society and was formerly the cruiser Hermione. She was bought from the Admiralty to replace the old wooden Warspite, which was burnt in 1918.

THE Royal Navy still makes its strong appeal to the youth of the country. With a far better knowledge of the prospects than their forebears could ever obtain, many more boys than can be accepted now apply to enter the service.

No longer may the King’s ships be manned by the sweepings of the gaols, by convicted smugglers who were too good seamen to be lost, or by pressed men who had not the least thought of enlisting, but who were soon infected by the spirit of the Navy. To-

The modern bluejacket has so much to learn and so much responsibility that only the best men will do. The Navy is willing to grant conditions which will appeal to the type of men that it wants. In this the service is limited by circumstances; for instance, nothing can make life in a destroyer or a submarine comfortable: but hard work is the salt of naval service. Once he has become accustomed to the violent motion of a destroyer as she cuts her way through any sea at high speed, the rating will seldom choose any other vessel; and the personnel of the submarine service is as keen as any to be found in the world.

Nowadays the pay in the Navy is quite good and is promptly paid; there is no trace of the old “ticket system” which persuaded men to desert to the Dutch. The food is as good and plentiful as could be desired. The quarters are as comfortable as the general design of the ship permits. Above all, the naval man who has finished his time is no longer a drug on the labour market, but is eagerly sought for by a large number of employers.

In any circumstances the knowledge that the rating obtains during his service is useful to him in after life. If he enlists for a long period, he is looked after by the Navy towards the end of the term and receives a vocational training which permits him to step straight out of the service into a good job. There are as many as fifty subjects of vocational training. This consideration, which is an expensive one to the taxpayer, was considered necessary to obtain the right type of lad. From the service point of view, however, it has its disadvantages also. The ambitious youngster, anxious to make the most of his opportunities and to get on in the world, has a tendency to enlist for the necessary number of years only, instead of regarding the qualification for a comfortable pension as being the best thing that a man can do for himself.

The lad who wishes to enter the service has more than one course open to him. Between the ages of eighteen and twenty-

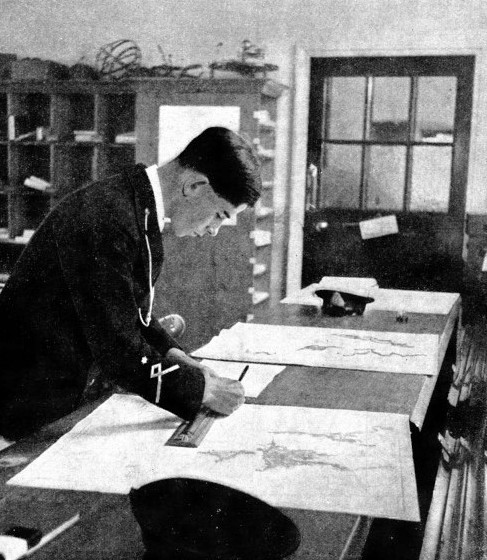

AT THE ROYAL NAVAL COLLEGE, Dartmouth. A cadet learning navigation is seen here working out the position of a ship from figures given by the instructor.

Exceptional lads of good physique and education are occasionally entered with fewer qualifications than those laid down. Boys who have received a good education may, on satisfying the examiners within a few months of entering the service, be transferred to the “advanced course”, where they are given a special course of training intended to fit them for early advancement. That advancement depends on many things; but a really good boy, keen, active and intelligent, has a remarkably good chance of reaching commissioned rank.

If he does not aim at anything quite so ambitious, but wants to follow the regular line, the prospects are by no means bad. Boys are graded second-

Ability has to be proved to gain able seaman rating at an advance of pay. Leading seaman is an intermediate rank which has to be earned by good work. In the British Navy the petty officer, wearing, after a certain seniority, a uniform somewhat resembling that of an officer, is treated with respect by all hands, forward and aft. This gives him an assured position. The Chief Petty Officer, earning nine shillings a day and upwards, holds a job of which any man may be proud.

In the engine-

On the other hand, a limited number of candidates are taken into the Navy as boys between the ages of fifteen and , sixteen and can serve their apprenticeship in the Navy itself, drawing pay and rations in the meantime. Stokers, whose work is different in these days of oil fuel from what it used to be with coal, enter between eighteen and twenty-

The various departments of the signal branch also offer excellent opportunities; but, with the exception of a few entered under the Special Service Scheme, they draw their recruits from the seamen boys who are already under training in one of the harbour establishments. They are selected after they have been sufficiently long under training to give their officers a good idea of character and ability. Then, at the age of seventeen and a half or eighteen, the recruits undergo a special course of training. This means not only better pay, but also exceedingly interesting work and allowances after a certain rank has been attained. The wireless telegraphy branch, a most important one in the modern Navy, obtains its recruits by similar means , these recruits also have fine opportunities.

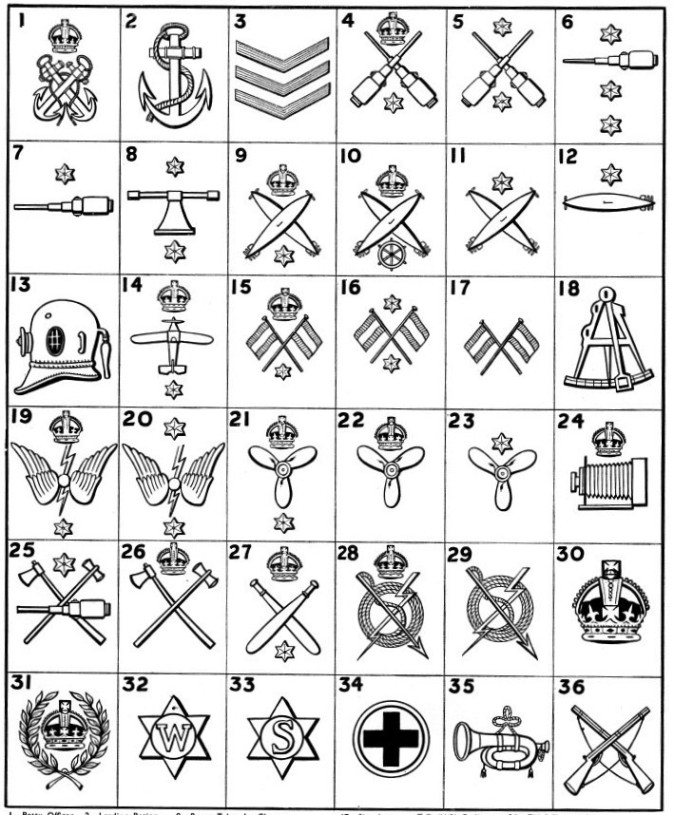

BADGES USED IN THE ROYAL NAVY

1. Petty Officer. 2. Leading Rating.

3. Good Conduct Badges: One stripe, 3 years and over; two stripes, 8 years and over; three stripes, 13 years and over. 4. Gunner’s Mate.

5. Director Gun Layer. 6. Captain of Gun 1st Class. 7. Chief P.O., P.O. and Leading Sea-

man, S.G. (not being Gunlayer or Gunner’s Mate), and Seaman Gunner. 8. Range Taker 1st Class. 9. Torpedo Gunner’s Mate. 10. Torpedo Coxswain. 11. Leading Torpedo Man. 12. Chief P.O., P.O. and Leading Seaman, S.T., and Seaman Torpedo Man. 13. Diver. 14. Observer’s Mate. 15. Visual Signalman 1st Class.

16. Visual Signalman 3rd Class. 17. Signalman, not T.O. (V S) Ordinary Signalman and Signal Boy. 18. Surveying Recorder. 19. Wireless Telegraphist 1st Class. 20. Wireless Telegraphist 3rd Class. 21. Mechanician. 22. Chief Petty Officer and Petty Officer

Stoker. 23. Leading Stoker and Stoker 1st

Class. 24. Chief Photographer. 25. Chief Armourer and Armourer. 26. Chief Shipwright.

27. Physical and Recreational Training

Instructor 1st Class. 28. Submarine Detector Instructor. 29. Submarine Detector Operator.

30. Regulating Petty Officer. 31. Master-

DISTINCTIONS OF RANK IN THE ROYAL NAVY

1. Admiral of the Fleet. 2. Admiral. 3. Vice-

4. Rear-

5. Commodore, 2nd Class. 6. Captain.

7. Commander. 8. Lieutenant Commander

9. Lieutenant. 10. Sub-

11. Warrant Officers (non-

14. Lieutenant R.N.V.R. 15. Engineer Lieutenant (All engineer officers wear a stripe or stripes of purple between gold stripes of their rank).

16. Surgeon Lieutenant (Medical officers wear red stripes between gold). 17. Instructor Lieutenant (Instructor officers wear light blue stripes).

18. Paymaster Lieutenant (All pay-

masters wear white stripes between gold).

19. Shipwright (Warrant Rank, silver grey stripe).

20. Wardmaster (maroon stripe). 21. Electrician (dark green stripe). 22. Ordnance Warrant Officer (dark blue stripe) 23. Midshipman’s “patch” R.N. (worn on lapel of Collar). 24. Naval Cadet’s “patch” R.N. (worn on lapel of Collar).

CAPS

25. Flag Officers. 26. Captains and Commanders

27. All other officers. 28. Petty Officer (Chief Petty Officer similar, but with badge No. 35).

29. Flag Officer’s Cocked Hat (Full dress).

30. Lieutenant’s Cocked Hat (Full dress).

31. Royal Marines, N.C.O. s and lower ranks (badge similar to No. 34 but one colour gilt all over, and lion attached to world).

Note.—Officer’s cap similar but with badge No. 34, and has red piping round crown.

CAP BADGES.

32. All officers of R.N. 33. All officers of R.N.R. (Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve the same but lettering R.N.V. over anchor). 34. Royal Marine Officers

35. Chief Petty Officer. 36. Petty Officer (confirmed).

Note.—Caps Nos. 25 to 28 have white tops for summer (May I to Sept. 30) or hot-

right down to top of red band.

In addition to steadily increasing pay with his rank, every lower deck rating in the deck or engine-

There is yet another allowance which goes with good conduct badges and the good conduct medal. This is earned by fifteen years’ service with continuous “Very Good” character.

Among the sidelines of the naval service which may be selected by the recruit are ordnance artificers, blacksmiths, joiners, painters, shipwrights, sick berth attendants, cooks, stewards and writers, each branch offering its own opportunity.

The rating of Chief Petty Officer is reasonably within the ambition of any youngster who enters the service and is willing to work hard and conform to discipline. This, however, need not be the end of his ambition. Promotion to warrant rank is almost entirely by vacancies. The slung sword of the warrant officer carries with it not only an interesting and responsible job, but also an assured position and, after a certain time or by gallant or distinguished service, the rank of lieutenant.

In addition to this, specially selected ratings in the seamen, signal and wireless branches may be promoted to the rank of sub-

During the last few years the chances of a smart lower deck man getting his commission, either before or after he has reached warrant rank, have been greatly increased. Some valuable officers have been obtained in this manner. In the old days almost the only way for a rating to be promoted to commissioned rank was through the Conspicuous Gallantry clause, although one or two exceptions were made for conspicuous services or seamanship. Lord Fisher was instrumental in allowing a number of warrant officers to receive their commissions, but it was at a time when they were too old to reap the full benefit. That was not what the lower deck wanted; ideas were changing and the rating demanded the same chance of rising to the highest rank as was possessed by the ranker officer in the Army. So, in 1912, the Mate Scheme was introduced.

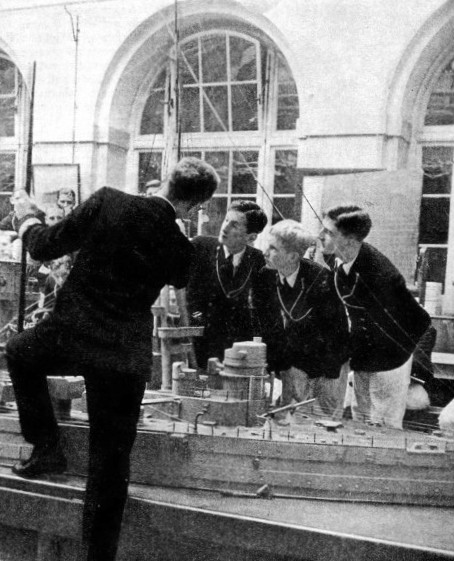

MODEL CRAFT are used for the instruction of young naval cadets. This photograph shows a class at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, which is the main gateway to a career as a naval officer. For over sixty years officers of the executive branch of the Navy have been trained at Dartmouth in Devonshire. In 1905 the college replaced an old wooden battleship, the Britannia, which was formerly employed as the training centre.

This gave reasonable opportunities for seamen and petty officers of outstanding merit to reach the ward room, with the promise of the highest advancement, through the intermediate rank of “Mate”, which was roughly equivalent to that of sub-

This scheme was the one in force during the war of 1914-

They did magnificent work, and were warmly welcomed in the ward room by their brother officers. As far as possible, they were considered by the Admiralty, which gave them appointments that promised to make the most of their ability without straining their financial resources too much. A number of them rose to the rank of Commander.

Between 1913 and 1930 over 450 warrant officers, petty officers and ratings were promoted to mates. But all was not right, and a committee on the whole question of promotion from the lower deck was appointed under Admiral Larken. On its recommendation the rank of mate was abolished and promising lower-

The last revolutionary change was in 1903, when Lord Selborne as First Lord, with the impetuous “Jackie” Fisher as First Sea Lord, changed the organization so that officers of the executive and engineering branches could enter and undergo their early training together.

A new preparatory college was erected at Osborne, in the Isle of Wight. For many years the young naval cadet spent two years of his course there and two at Dartmouth, where a magnificent building on shore replaced the picturesque but inconvenient “wooden wall”. Latterly Osborne has been closed, and the Dartmouth cadets go straight to the college from the preparatory school.

A new preparatory college was erected at Osborne, in the Isle of Wight. For many years the young naval cadet spent two years of his course there and two at Dartmouth, where a magnificent building on shore replaced the picturesque but inconvenient “wooden wall”. Latterly Osborne has been closed, and the Dartmouth cadets go straight to the college from the preparatory school.

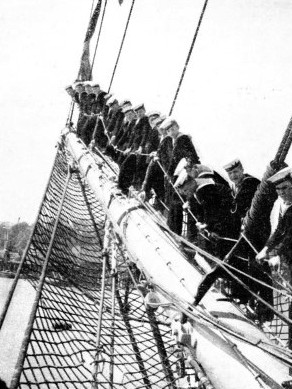

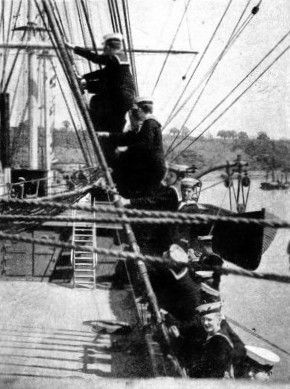

BOYS AT WORK on the bowsprit of the Arethusa. From the time when the first training vessel of this name was moored in the Thames in 1873, this particular institution, supported by charity, has prepared over 3,500 boys for the Navy.

In addition, a few cadetships in the Navy are given to youngsters who have trained in the mercantile training ships Worcester and Conway, and in the Pangbourne Nautical College. Occasionally, in times of stress, Royal Naval Reserve officers from the big shipping lines have been transferred to the regular Navy in supplementary lists.

Most of the budding admiral’s time as a cadet is spent on shore, but he receives his first taste of the sea in the training cruiser Frobisher, which generally cruises to West Indian waters. Sometimes he has a spell in a big ship, where he messes in the gun-

When he has passed his first professional examinations, he becomes an Acting Sub-

WHERE BRITISH SAILORS HAVE BEEN TRAINED. H.M.S. Impregnable, an old wooden training ship, in which, between 1852 and 1928, boys were trained for service in the Navy.

A Sub-

He may decide to specialize. Gunnery, torpedo and navigation are the principal branches, and are generally chosen after an officer has served three or four years as lieutenant. That means further training ashore for considerable periods, for the specialist officer has a scientific job. The officer may, however, decide to remain “salt horse”, or to specialize in one of the minor branches. When he has served eight years, he receives automatic promotion to the rank of Lieutenant-

He may decide to specialize. Gunnery, torpedo and navigation are the principal branches, and are generally chosen after an officer has served three or four years as lieutenant. That means further training ashore for considerable periods, for the specialist officer has a scientific job. The officer may, however, decide to remain “salt horse”, or to specialize in one of the minor branches. When he has served eight years, he receives automatic promotion to the rank of Lieutenant-

BOYS CLIMBING aloft in the Arethusa.

Promotion from Lieutenant-

The engineer officers, apart from those promoted from the ranks, enter Dartmouth with the others. When they decide to specialize they go to Keyham, near Devonport, where the Royal Naval Engineering College is situated. There are, however, still a number of engineer officers who entered the Navy under the old system before common entry was introduced. The

Accountant Officers have to be bankers and have an intimate knowledge of other businesses, especially victualling and law.

Pay and conditions have been greatly improved of recent years, so that the ambitious young man can now serve his King without having a large private income. Although there are apt to be disappointments in a naval officer’s career, it is a most attractive one for the man of the right character.

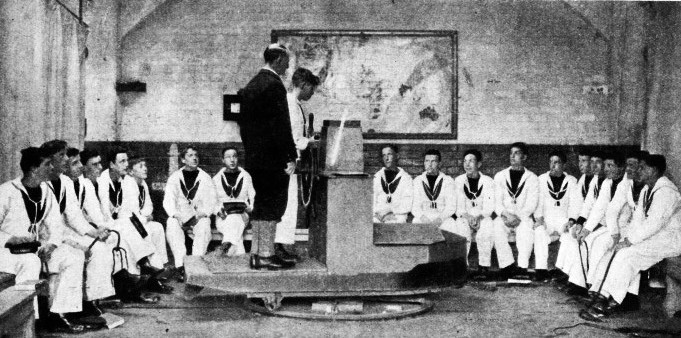

PHYSICAL TRAINING AND GENERAL EDUCATION play an equally important part in the training establishments for boys wishing to join the ranks of the Navy. This picture shows an instructor teaching a class the principles of steering at the Shotley establishment near Harwich.

You can read more on “The Navy Goes to Work”, “The Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve” and “Signalling at Sea” on this website.