© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Royal Marines

Since its formation in 1903, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve has grown in importance as well as in numbers. A volunteer organization, with divisions in many parts of Great Britain, the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve offers to the sea-

EMBARKING AT SOUTHAMPTON in the transport Neuralia for Malta and Aden in September 1935. Royal Marines in helmets and khaki service dress uniform are seen in this photograph. The Neuralia, a British India twin-

THERE are still many people who know little about the status and duties of what was formerly known as the Regiment of Sea Soldiers. The Royal Marine Corps is really a link with the days when soldiers were carried on board ship to do the fighting; the business of the sailor was merely to take the vessel from place to place when ordered to do so by the knights. It was certainly not the sailor s duty to take any part in a battle, although then, as now, it was difficult to keep the tar out of the thick of things when there was any fighting in his neighbourhood. In Tudor days the sailor had to rely so much on his own efforts in distant waters that he took to the handling of the guns as a duck takes to water. It was the essential difference between the sailors who handled their own weapons and soldiers at sea who were transported in ships about which they knew nothing, that settled the fate of the Spanish Armada. There was still, however, good use for soldiers in a ship’s company, especially when the sailors were picked up by the press gangs as required and thrown back on the streets at the end of each commission. Sharpshooters were useful in the tops and on deck to pick off the enemy officers, for the sailors were seldom trained in musketry; they handled the big guns and the management of the ship.

Nearly all ships carried a few soldiers in addition to their mariners, and the matter was more or less regularized in 1664 when Charles II and his brother the Duke of York, working with a thorough knowledge of naval affairs, formed a new force of Marines. This was first known as the Admiral’s Regiment, after the Duke of York, who was then Lord High Admiral. In the Dutch Wars the Marines showed their utility in the organization of a fighting ship. The City of London was duly proud of the fact that the first regiment had been raised largely from its train bands. The Royal Marines still have the privilege of marching through the City with bayonets fixed, drums beating and colours flying.

In the early, days nothing in the King’s service was stable. The new regiment underwent many changes before it was soundly established in 1755. The manning of the Navy was one of the country’s greatest problems, and in times of peace it had been badly managed. The sweepings of the gaols and the landsmen who were not quick enough to dodge the press gangs were considered good enough to take the King’s ships to sea; but the long-

Frequently during the life of the corps its numbers have been insufficient for its purpose, and detachments of many regiments have been drafted to sea when there were no Marines available. In the eighteenth century about half the army served on board ship at some time or another, including even cavalry regiments. This gave rise to the old gibe about the Horse Marines. Even during the war of 1914-

The Marines proper, however, are an integral part of the Navy. They take their place between the Navy and the Army in combined reviews. Until well after the war the corps was divided into two parts, the Royal Marine Light Infantry and the Royal Marine Artillery. They were known as the Red Marines and the Blue Marines respectively, from differences in uniform, which disappeared many years ago.

Formerly some of the Marines served for five years with the colours and seven with the Royal Fleet Reserve. Now all the Marines start their twelve years’ service at the age of eighteen. If they reach the strict standards required they may serve a further nine years for pension. A high standard, both physical and moral, is necessary, and the recruit is made clearly to understand this before he joins. This is one reason why the corps is so free from desertion.

When he is first enrolled the Marine goes to the depot at Walmer, near Deal, in Kent. There he goes through a course of intense preliminary training. Then he is allowed to choose his division, as far as numbers allow, and becomes attached to Portsmouth, Chatham or Plymouth. He completes his training at a division, not necessarily his own, and on rare occasions the depot training has to be cut out and he goes to a division at once.

Versatility of the Corps

The training is so intensive that before the Marine is considered fit for ordinary corps duty he must become a first-

Besides the sentry and orderly duties allotted to them, the Royal Marines have their full share in keeping the ship clean and efficient. The after part is their particular care and they are always in complete charge of one big gun turret and part of the ship’s secondary battery, generally the antiaircraft guns. On one occasion the corps proved itself capable, almost alone, of manning a cruiser. H.M.S. Indefatigable, on the West Indies Station, had only a handful of naval officers and was otherwise manned entirely by Marines, who made her a particularly smart ship and a credit to the squadron. Naturally enough there is keen rivalry between the sailors and Marines.

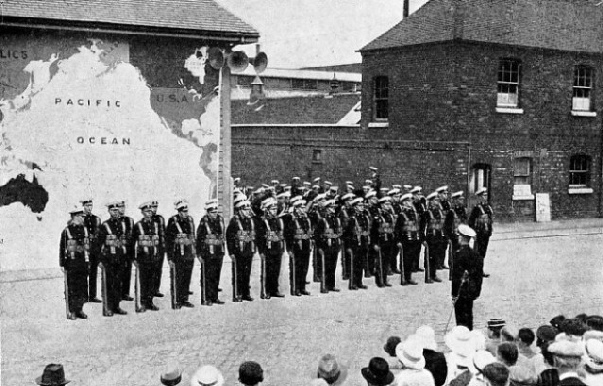

A DEMONSTRATION DURING NAVY WEEK, given by the King’s Squad of the Royal Marines. The Royal Marines are based at Portsmouth, Chatham and Plymouth, and the training depot is at Walmer, near Deal, in Kent.

In addition to innumerable ship duties, the corps is the spearhead of any landing operations that may have to be carried out by the Navy. Bluejackets are often landed as well, but the Royal Marines are the first to go. There is a proper battalion organization in every fleet. Every ship present provides its quota to this battalion — sometimes a platoon, sometimes perhaps only a machine-

The young Marine officer has to work as hard as the Marine under him. The officer generally enters between the ages of seventeen and eighteen and a half. He, too, starts at the Walmer Depot. After his preliminary instruction he goes on to one of the divisions and joins his opposite number, the young naval officer, in many courses of instruction. In the division he is a second-

As a subaltern or as a captain, the officer is fully employed. His services are always in demand and he has a fair opportunity of gaining personal distinction. Majors are embarked as Fleet Royal Marine Officers in all the fleets except the Home and the Mediterranean Fleets, which are large enough to justify the rank of lieutenant-

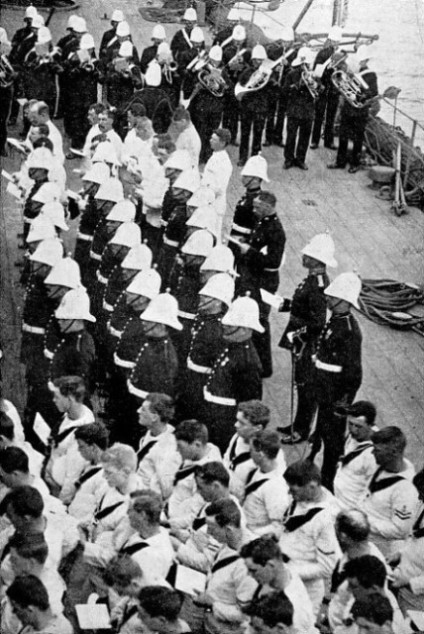

SUNDAY MORNING CHURCH PARADE forms part of the regular routine on board ships of the Royal Navy. This photograph, taken on board H.M.S. Neptune, shows a detachment of Royal Marines and a Royal Marines band, which plays the hymns. H.M.S. Neptune is a cruiser with a displacement of 7,030 tons, completed in 1934. She has an overall length of 554 ft. 6 in., a beam of 55 ft. 2 in. and a draught of 16 feet.

The Adjutant-

Perhaps the greatest asset of the Royal Marines in maintaining their place in the King’s services is the pride that every member takes in the corps, and the traditions and honours which foster that pride. Many years ago it was desired to give them battle honours on their colours, after the fashion of the regiments of the line, but King George IV pointed out that it would want a frigate’s fore-

You can read more on “In the Royal Navy”, “The Navy Goes to Work” and “Navy Week” on this website.

You can read more on “The Fleet Air Arm” in Wonders of World Aviation