© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

London’s Link With the Sea

To the Port of London come large ships and small ships carrying passengers and cargo along its sixty-

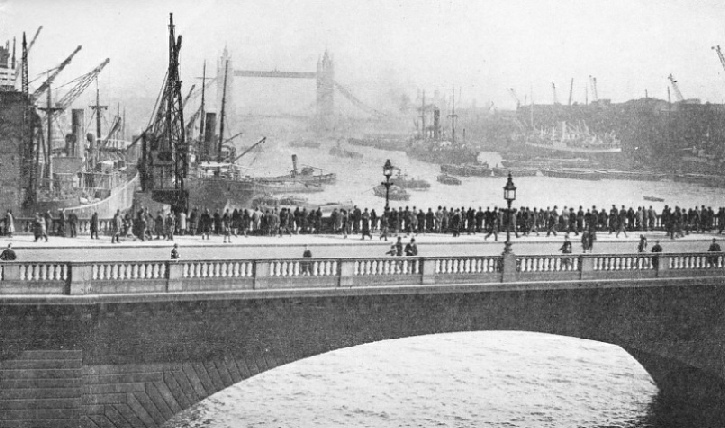

IN THE UPPER POOL from London Bridge, one of the busiest sections of the Port of London. The Port of London consists of the tidal portion of the Thames, from the sea up to Teddington in Middlesex, a distance of sixty-

THE Port and City of London owe their origin and development to the River Thames. London was an established trading centre before the Roman occupation of Britain. Writing about the first century A.D., the Roman historian Tacitus described London as crowded with traders and a great centre of commerce.

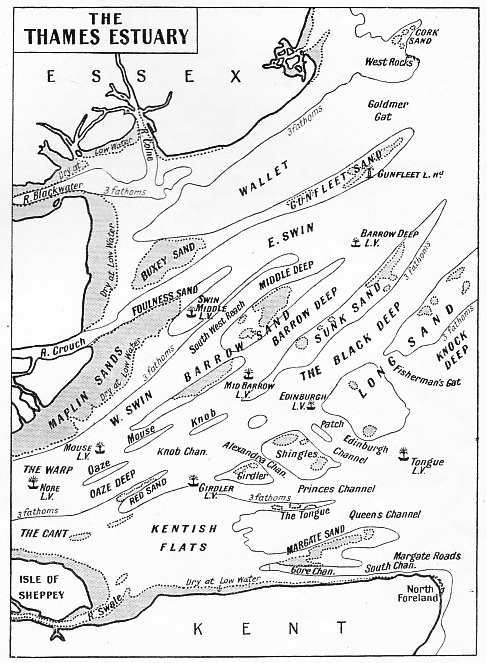

Let us, in imagination, enter the Thames and sail up to the docks. We have come up the English Channel and taken our pilot from a cutter at Dungeness. We have passed through the Downs, between the Kentish coast and the Goodwin Sands, and have rounded the North Foreland. We are now turning westwards to enter the river. The Tongue lightship stands as an outpost of the Thames, at the junction of Princes and Edinburgh Channels. All ships of any size entering London from the English Channel or lower North Sea must pass near this lightship. It shows alternate red and white flashes.

The chart reveals four channels leading towards London. The first, nearest the Kentish shore, leads through Margate Roads to the South Channel and the Nore, terminating in the shallows of the Kentish Flats. It is used by the pleasure steamers of shallow draught which call at Margate and Ramsgate. Small cargo steamers coming from Ridham Dock, in the Swale, between the Isle of Sheppey and the mainland, also use it.

Next comes Queens Channel, which also leads to the Kentish Flats and is rarely used. Princes Channel was once the principal entry to the river. But because of the increasing size of ships and of the channel’s silting up, it is now used only by coasting and small craft. Alexandra Channel has silted up and is now out of service. Edinburgh Channel alone is used for the large number of big ships entering and leaving London. A narrow passage between the Long Sand and the Shingles, it is split into two portions by a sandbank known as “The Patch”. Inward-

At the foot of the Long Sand swings Edinburgh Channel lightship, showing a white flash every five seconds. Here we turn south-

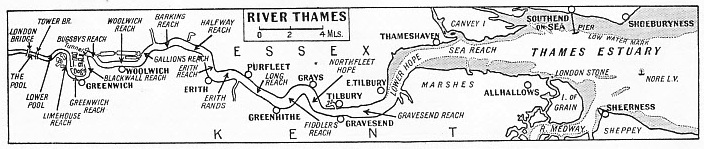

LOOKING EAST, towards the sea, along the winding course of the River Thames towards the Tower Bridge and the Isle of Dogs. Near the Tower Bridge is St. Katharine’s Dock, and farther downstream the London Docks. Lower down, on the opposite bank, on the south side of the river where it bends to form a great U, are the Surrey Commercial Docks. The U curves about a strip of land known as the Isle of Dogs, where lies the great system of the West India and Millwall Docks. Beyond this photograph, when the loop is complete, come the East India Docks, the Royal Victoria and Albert and King George V Docks. After these there intervenes a stretch of fifteen miles before the Tilbury Docks, in Essex, are reached.

The Girdler lightship is moored at the western end of Princes Channel, on the northern edge of the Kentish Flats. This ship shows a white light of one and a half seconds’ duration every half minute. We are now in the Knob, the meeting place of Princes, Alexandra, Edinburgh and Barrow Channels. Just beyond is a bar of sand, the Oaze. It can be passed either to the north or to the south, through the Oaze Deep, to the “Warp”, where the Nore lightship lies. The Nore is generally regarded as marking the mouth of the Thames.

One of the most famous lightships, the Nore was first placed in position in 1731. The present ship, which is built of wood, dates from 1839. She shows a white light of five seconds’ duration every half minute and marks the eastern end of the Nore Sand. The seaward limit of the Port of London Authority, the governing body of the Port of London, passes across the river near here. This limit is an imaginary line drawn from Havengore Creek, on the Essex side, to Warden Point, on the Isle of Sheppey.

The Essex shore is bordered by the Maplin Sands, which dry at low water. Then comes Swin Channel, used by steamers going to Clacton and Felixstowe, and the creeks and rivers of Essex. Barrow Sand divides the Swin from Barrow Deep, the passage most used by north-

Another long barrier of sand, the Sunk, follows, and then Black Deep. Next come Long Sand and Knock Deep; this Deep is seldom used. The Kentish Knock, with Galloper Sand, farther to the north, forms the outermost danger to shipping.

Beyond the Nore the river proper is entered, and the shores, hitherto distant and low-

Southend pier juts out like a long finger into the river. Off it can be seen steamers awaiting work or to be scrapped. We are now in Sea Reach, the fairway of which is marked by four red buoys. The Essex side is marked by a continuous row of towns -

THE COURSE OF THE THAMES from the sea to London Bridge is indicated on this scale map of the busiest section of the Port of London. The control of the Port Authority extends down the river to the Nore light-

Rows of gleaming silver tanks next attract attention. Here is London’s oil port. Tankers may be seen alongside the jetties discharging their liquid cargoes. Small tank vessels take oil and petrol from this port to depots higher up the river and to many coastal ports. The river now narrows and turns south into the Lower Hope. “Hope” is derived from an Icelandic word meaning “bay” or “haven”. The word recalls the days when Norsemen and Vikings sailed up the stream on raiding expeditions.

We now come to Gravesend Reach, an important point. Liners, cargo steamers, coasting vessels, barges, tugs, warships and large sailing ships can sometimes be seen anchored here. In the Reach they wait for the tide, or for orders, on their way to London. Among the smaller craft are black sailing-

At this part of the river, a ship being piloted exchanges her sea pilot for a river pilot. Here, also, a launch bearing a doctor visits all inward-

Until 1929, passengers wishing to join liners at Tilbury were taken out in tenders from a small landing stage, and were disembarked by the same means. But in 1929 a new stage was opened. This large pontoon stage, which rises and falls with the tide, is 1,142 feet long. It will accommodate alongside the largest ships, at any state of the tide and is connected by covered gangways with a fine Custom Examination Hall and also with Tilbury Riverside Station.

Next comes the old entrance to Tilbury Docks. These were opened in 1886 to relieve the congestion in the older docks farther up the river. In 1929 extensive work undertaken to improve them was finished. The improvements consisted of a new entrance lock -

Between the old and new entrances a jetty, 1,000 feet long, equipped with cranes and railway lines, has been built.

Ships can thus load or unload pare cargoes without going into the docks. It is largely used by Dutch motor-

The town of Gravesend, the sea gate of London, lies on the opposite side. Built on the first rising ground seen after entering the river, it has always been a place of importance. Only a “hythe”, or landing place, is mentioned in Domesday Book, but soon after the Norman Conquest a town was built. Queen Elizabeth granted a Charter of Incorporation and a coat of arms -

The town long retained the sole right of conveying passengers by water to London. It was burnt by the French in 1377. Beneath the chancel in the old church was buried Pocahontas, the Red Indian princess who married one of the early Virginian “adventurers”.

To-

A SIMPLIFIED CHART of the Thames Estuary, showing the various channels that lead towards London. The first, nearest the Kentish shore, passes through Margate Roads to the South Channel, and is used by shallow-

Proceeding up-

Swanscombe marshes project into the river, ending in Broadness, where there is a lighthouse. The river turns sharply here into St.

Clement’s, or Fiddlers Reach.

At the end of Fiddlers Reach and the beginning of Long Reach stands Greenhithe.

At the end of Long Reach, on the Kentish side, the River Darenth (or Dartford Creek, as it is generally called) joins the Thames. This creek was once wider and deeper. The remains of a Roman galley were found there.

Beacon Hill, at Purfleet, is a picturesque landmark, visible for many miles up and down the river. Turning up Erith Rands we pass Erith, the chief trades of which are coal and timber. East Indiamen used sometimes to lie off Erith awaiting to sail. The town was once famous for ballast.

Erith Reach turns almost north to Halfway Reach. On either side of the river at this point there are embankments. They have to be carefully maintained, as the high-

Special accommodation exists for handling and storing frozen meat, and there are large granaries at Victoria Dock. In King George V Dock ships can be unloaded into lighters from either side at once and on to the quay. On the south side of the dock are seven “dolphins” or wharves built out into the dock, connected with the “shore” by bridges. Cranes are placed on the “dolphins”, and lighters can lie between them and the main wall.

The entrance lock to King George V Dock is 800 feet long, with a depth of 45 feet. There is a dry dock at the western end 750 feet long. Albert Dock has two locks into the river and two dry docks at the western end. The entrance from the river at the far end of Victoria Dock has been closed for large craft. A ship from that end must traverse the whole length of Victoria Dock, Albert Dock and, if using the King George V Dock entrance, a part of that dock to get into the river.

Returning to the river, at Gallions Reach we find ourselves opposite Woolwich Arsenal, with its large crane, a conspicuous landmark. Then follows Woolwich Reach, one of the longest “straights” in the river between Gravesend and its source.

There are buoys in Woolwich Reach at which idle ships can lie up, as can cargo steamers wishing to unload into lighters without entering a dock. Here, too, may often be seen the Post Office cable ships Monarch and Alert.

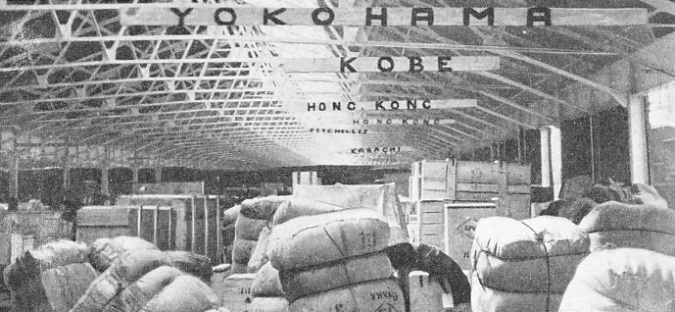

EXPORT CARGO in the transit sheds on the south side of King George V Dock. This dock, opened in 1921, forms, with the Royal Victoria and Albert Docks, the most important group of London’s dock systems. The docks have special facilities for dealing with frozen meat, tobacco and grain. Agricultural produce and general cargo are also handled.

We turn now into Bugsbys Reach. On the northern side, Bow Creek, the entrance to the River Lea, joins up, and we come to East India Docks. These date from 1806, and were begun by the old East India Company for the accommodation of their ships. Many well-

On the river-

The river now describes a large “U”, composed of Blackwall, Greenwich and Limehouse Reaches. The West India and Millwall Dock system is enclosed in the “U”, with entrances into both sides of the “U”. The West India consists of the Import, Export and South Docks. Millwall Dock, at the bottom of the “U”, resembles a capital “L” in shape. The entrances to West India Dock, cutting across the top of the “U”, form the Isle of Dogs. The origin of this name is unknown. A probable explanation is that the hunting dogs of the Kings, who lived at Greenwich, were kept on the island.

The West India Docks were almost the first built in London for handling cargo. They were opened by the famous William Pitt in 1802, and are now the principal centre of the hardwood trade. They are used also by Harrison liners from Demerara and the West Indies, Union-

Millwall Dock was built in 1868 by a private company. It is surrounded by large granaries, grain being “pumped” by special apparatus direct from the ships. Elder Dempster liners from West Africa, Swedish Lloyd mail steamers from Gothenburg and other Danish and Swedish ships use this dock. There is also a much-

Past Greenwich Observatory

The West India and Millwall Docks were two distinct groups until 1929, when they were linked by ship passages. A fine new entrance lock has been constructed which enables these famous docks to be used by large modern ships.

Returning to the river in Blackwall Reach, we shall probably see the cable-

Greenwich next claims attention. An imposing palace stands on the river bank with a wooded hill rising behind. It is topped by the domed buildings of Greenwich Observatory and by the famous “Time Ball”, which drops at one o’clock Greenwich Mean Time every day.

There are moorings just above Greenwich Pier for large ships. At least two tramp steamers or cargo liners are generally seen discharging cargo into lighters there. Sometimes, during the summer, large cruising liners of foreign companies use these moorings while their passengers are visiting London.

Having passed through Greenwich Reach we turn into Limehouse Reach. On the south bank is the entrance to Deptford Creek, where the little river Ravensbourne enters the Thames. The district on one side of it is known as “the Stowage”. The repair depot of the General Steam Navigation Company, a firm much in evidence in these Reaches of the river, is situated here.

Deptford is next passed. Here was the former dockyard originating in a storehouse established by Henry VIII about 1513. In 1581 Queen Elizabeth visited Sir Francis Drake in the Golden Hind, which was anchored off the Yard, after his voyage round the world. Here also Peter the Great of Russia worked for some time.

THE WEST INDIA AND MILLWALL DOCKS. This impressive aerial view shows the linked group of docks that covers 133½ acres of water with five miles of deep-

A large part of the southern shore is occupied by the Surrey Commercial Docks, the principal timber docks. The largest of these basins is believed to have been originally the trench which Canute dug in 1016 to enable his ships to sail up the Thames without passing the neighbouring bridge. Four separate companies once owned these docks, the oldest of them, the Greenland, owning the basin which was the resort of whalers. These docks are now used by 14,000-

Surrey Commercial Docks have altogether a water area of 147 acres, a land area of 230 acres and five miles of quays. Several of the docks were originally “Timber Ponds”, intended for the storage of timber in water. But recently some have been converted into docks, and others filled in to provide storage space. Half a million tons of timber are dealt with annually. There are “streets” of stacked wood, for these docks are the largest timber stores in Great Britain. Other commodities dealt with are grain (500,000 tons annually), paper and dairy produce.

Surrey Commercial Docks have altogether a water area of 147 acres, a land area of 230 acres and five miles of quays. Several of the docks were originally “Timber Ponds”, intended for the storage of timber in water. But recently some have been converted into docks, and others filled in to provide storage space. Half a million tons of timber are dealt with annually. There are “streets” of stacked wood, for these docks are the largest timber stores in Great Britain. Other commodities dealt with are grain (500,000 tons annually), paper and dairy produce.

The Greenland Dock, which is on the site of the Howland Great Wet Dock, constructed about 1696, is the home of many liners from Canada and the United States. Large quantities of provisions, such as cheese, bacon, grain, flour, and fruit are handled.

Many “tramps” of Scandinavian nationality are always seen at the Surrey Docks.

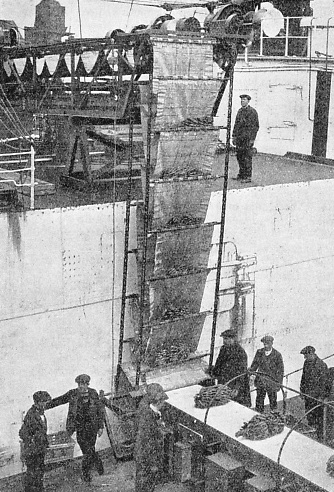

A CONSIGNMENT OF BANANAS at the East India Docks being unloaded by means of conveyer bands.

Returning to the river, on the southern bank, near the Commercial Dock entrance, we can see the wharf to which all objects found floating in the river are taken. Here also is the “King’s Pipe”, where once smuggled tobacco captured by Revenue Officers was burnt.

At the top of Limehouse Reach we turn into the “Pool”. On the northern shore of it is Shadwell and Wapping, and one of the entrances into London Docks. Begun in 1802, they are now used by coasting and “short trade” vessels trading to the Continent. Special warehouse accommodation is provided for brandy (120,000 casks), wine (27,000 “pipes”), wool, ivory, canned fruits, skins and other commodities.

Round the bend of the Pool, Tower Bridge comes into sight ahead, and large warehouses are seen on either bank. The last dock, St. Katharine’s, stands on the north bank close to the bridge. Opened in 1828, it is on the site of an old religious house and is surrounded by high warehouses. Formerly shipmasters were warned to keep the yards of their sailing ships at such an angle as would prevent their going through the windows of the upper storeys. Tower Bridge was built in 1894 to relieve the traffic pressure on London Bridge. It has two lifting arms in the centre to allow shipping to pass. The cost of raising these arms is £5. A tug is stationed near by to assist vessels in negotiating the passage.

Beyond Tower Bridge is the Upper Pool. On the northern bank is the grey pile of the Tower, with the white tower of the Port of London Authority building behind. Next comes the Custom House. The present building was opened just over 100 years ago, but such an office has existed on this spot for over 500 years. Round a small pontoon may be seen the launches of the Waterguard, the branch of the Customs engaged in keeping supervision over ships lying in the river.

We are now at London Bridge and our interest in London as a port largely ceases.

In 1900 a Royal Commission was appointed to consider the future of the port. As a result of the Commission’s findings, in 1908 the Port of London Authority Act was passed. The Port of London Authority was established to take over and administer as one unit all the docks and the tidal portion of the river. The members of the Authority are appointed by such interested bodies as the Admiralty, and the County and City of London, or are elected by shipowners, merchants and others using the Port. Its area of control extends from Teddington in Middlesex to the sea -

IVORY TUSKS being checked and weighed at the ivory warehouse of the London Docks. The London and St. Katharine’s Docks system has an area of 123½ acres, including forty-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “His Majesty’s Customs Service”, “Pilots and Their Work” and “The Work of Trinity House” on this website.