© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Thames “Butterfly” Boats

As with the Clyde and West Coast of Scotland passenger paddle steamers, the packets that maintain services between London and neighbouring holiday resorts have a history which goes back to the first years of steamships

THRONGED WITH HOLIDAY-

“BUTTERFLY BOATS”, as the deep-

The first steamer to carry passengers on the Thames is seldom mentioned in history books. She was the little Richmond, which was put on the London-

So progress might have been held up, but by the end of 1814 the little steamer Margery was bought from the owners who had been running her on the Clyde. She made the passage round to the Thames under sail, and was put on what had been known as the Long Ferry, between London and Gravesend. She ran from Wapping Old Stairs, close to the London Docks, to Milton, below Gravesend, doing the passage down one day and returning on the next. After one year’s service she was sent out to the River Seine, France.

The promise of her first few months of running was sufficient to encourage other parties to buy the steamer Arqyll, on the Clyde, for the same purpose. She was 72 feet long with a burden tonnage of 74, the nominal horse-

The Argyll was renamed Thames, and with new engines did well for a time. Then she was relegated to the Gravesend service again, being replaced on the Margate run by the Regent, which was built at Rotherhithe in 1816. She was a beamy little ship of 112 tons burden and her engines of 24 horsepower were independent, either driving its own paddle, with the boiler placed between them. Her great fault was that, in the desire to obtain the high speed which was demanded by her passengers, everything was built lightly, in a manner which would not be passed by the inspectors to-

Meanwhile the services to Gravesend were improved and better steamers began to run on a regular schedule up-

A number of experimental steamers were brought out which might well be described as freaks. Of these the most prominent was the London Engineer of 1818. She was a fine vessel in her day, but peculiar in that her paddle-

She was fitted with a nice saloon aft, having the luxury of upholstered settees, while the passengers in the cheaper fore cabin had to be content with wooden benches. She was too big a ship to have her sail set on the funnel, and was given two proper masts, although the funnel with its decorated top was nearly as tall as they were.

The “Eagle” Tradition

Several attempts were made to run a “straight-

The steamers on the Long Ferry, and from London to Greenwich and Woolwich, were much lighter in construction and, as the competition increased and more owners put their ships on the run, reckless racing and cutting in became the rule. The sections above London and through the bridges to Richmond demanded yet another type of light, construction and draught so that the service might be maintained independent of the tide. Accidents were numerous on all three sections, occasionally fatal, but the general public took little notice of them and continued to patronize the steamers in ever-

On the Margate run a great difference was made when the first of the famous Eagles was built. She was a private venture of Thomas Brocklebank, and was built in 1820 at his own yard at Deptford. In the following year she was put on to the Margate run, where her burden of 170 tons, her accommodation and her speed, attained by two engines of 20 nominal horse-

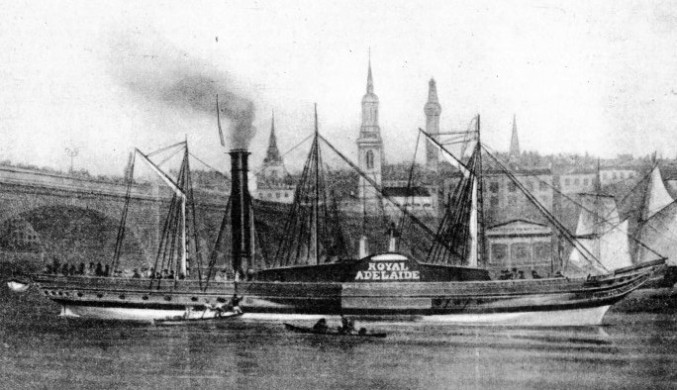

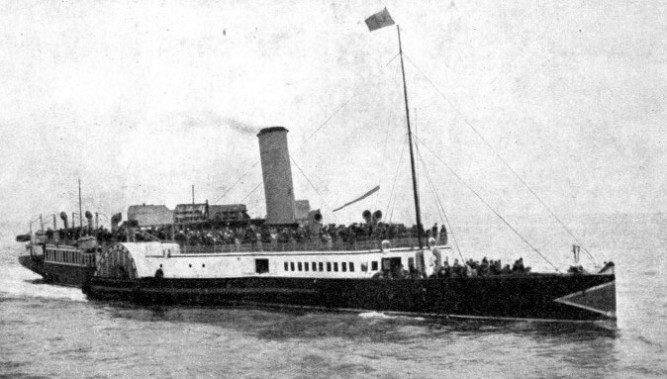

AN EARLY EXCURSION STEAMER which was employed on the service between London, Gravesend and Margate. The Royal Adelaide, built in 1830, was typical of the many paddle steamers to be seen on the London River during that period. Competition for the river traffic was keen, for the railway to Gravesend was not built and the Princess Alice disaster had not yet shattered the confidence of the public.

Until the advent of the Eagle these steamers were regarded as being too valuable to entrust to the care of a Merchant Service officer, and half-

The river steamers had improved nearly as rapidly as those on the Thanet run, speed being the great consideration. In 1821 the crack ship on the river was the Swiftsure, the pioneer of the Gravesend Steamboat Company, and on a burden of only 105 tons she had engines of 30 nominal horse-

In 1828 the Gravesend service was still further improved by the commissioning of the Sophia Jane, by far the biggest steamer on the river run, with her burden of 143 tons. She afterwards had the distinction of being the first steamer to go round the Cape of Good Hope to Australia.

A number of steamboat companies were founded on the river and on the coast. On the river two of the companies were particularly interesting. One was the Sons of the Thames Company, which was founded by a number of steamboat captains when their owners appointed pursers to collect the fares.

13½ Knots in 1836

The captains maintained that their dignity was wounded, but it is far more likely that it was their pocket that was hurt, for in the early days there was no method of checking the money that they received, nor of preventing gross and dangerous overcrowding. The other was the Watermen’s Steam Packet Company, mostly interested in the services above Woolwich only. This company was founded by the watermen of the river when they discovered that they could not possibly drive the steamers off the waterway, so determined to own them instead.

The Star and Diamond Companies were keen competitors on the Gravesend route, and built some remarkable steamers. The most striking was undoubtedly the Ruby, which, built at Blackwall in 1836, was the fastest ship afloat in her day. Her hull was 155 feet long between perpendiculars, 19 feet in beam and 10 ft. 2 in. in depth, her burden being 272 tons. Her two side-

All this time there were a number of smaller companies and owners trying to get their share of the business, but few of them lasted for long. Many of their steamers were considered by the Admiralty to be fit to carry a reasonably heavy armament in war-

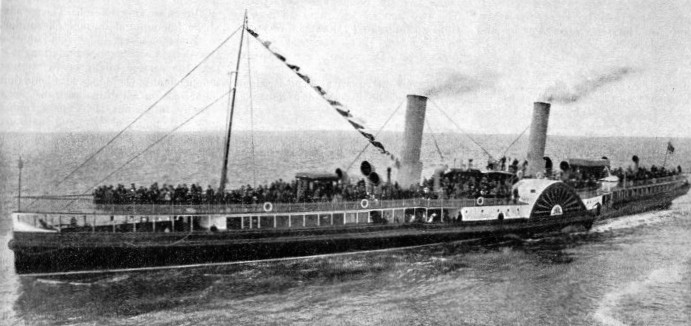

THE LARGEST EXCURSION STEAMER for many years was the famous La Marguerite, built by the Fairfield Yard in 1894. Of 2,205 tons gross, she was designed to run from Tilbury to Margate, Boulogne, Calais and Ostend. Her length was 330 feet, her beam 40 feet and her depth of hold 13 ft. 7 in. She was sold to the Liverpool and North Wales Steamship Company in the winter of 1903-

Racing was forbidden, but it constantly occurred. The wash claims made by barges and other interests on the river encouraged the evolution of many ideas to reduce the waves raised by the paddles. The Propeller of 1840 was not a screw boat, as her name suggests, but was fitted with extraordinary paddles. These consisted of single iron blades which dipped into the water almost perpendicularly and were forced backwards by an iron arm having a motion similar to that of a grasshopper. The Propeller raised no wash, but she was extravagant in coal.

The Blackwall Railway Company, which normally ran services on the river only, built the Prince of Wales in 1840, which attracted great attention. She was the first iron-

When the railway was opened as far as Gravesend in 1848 it appeared that the Long Ferry was doomed, and that the steamers would be used only for short distances in London or close to the metropolis, or else on the long excursions to the coastal resorts. Several of the smaller companies went into liquidation but the remaining ones, and some which were floated specially, found plenty of employment.

There was another little boom at the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851, when London was packed with visitors from every country. They regarded a trip on the river as being an essential part of their holiday. There were also periods of reckless rate-

Epoch-

By the 1850s the railways were taking an enormous number of holiday-

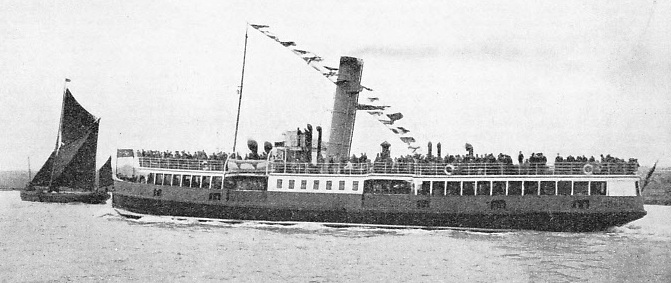

AT THE ANNUAL THAMES BARGE RACE, described in the chapter “Thames Sailing Barges”, Thames packets often act as committee boats and grand stands. This photograph shows the famous Royal Daffodil at the 1934 barge race. Built in 1906 for the River Mersey ferry services, the Daffodil won fame for her part in the Zeebrugge action on St. George’s Day, 1918. Now known as the Royal Daffodil, she belongs to the New Medway Steam Packet Company. A twin-

It was one of these former Clyde steamers, the Princess Alice, whose tragic end checked the development of the Thames passenger business for many years. She was one of the crack ships of the London Steamboat Company and, by her size and her imposing appearance with two funnels, was highly regarded by passengers. The more practical Clydesiders had condemned her as being unstable and weak, and the addition of extra saloon accommodation when she came south had made matters worse.

In September 1878 she was returning from an excursion to Gravesend and Sheerness with about 700 passengers on board. At about 8 o’clock in the evening, when she was approaching Woolwich, she was run down by the screw collier Bywell Castle, which hit her just forward of the starboard paddlewheel and cut right through her side into the machinery space, the biggest compartment in the ship. She immediately began to roll over and founder, breaking her back. A panic ensued.

There was no time to get out the inadequate lifeboats which she carried, and there were far too few lifebuoys. Within five minutes she had gone down in the deepest part of the river, carrying with her about 550 of her passengers. The remainder had extraordinary escapes, and the disaster will always be remembered on Thames-

The catastrophe caused a profound impression throughout the country. That a ship should be permitted to carry hundreds of passengers without Lloyd’s classification for her construction, and without any supervision as to the life-

The first attempt to regain favour was rather a half-

The next step was the building of three new little river steamers to run between Greenwich and Battersea, the Orlando, Celia and Rosalind. They were built on the Tyne, and were of a new standard for the river service.

The First “Belle” Steamer

Just over 100 feet in length, with a beam of 11 feet, they drew only 3 ft. 6 in. of water, could carry 300 passengers and had good saloons forward and aft. Their compound engines gave them a speed of 10 knots, and were exceedingly economical for their day, and the greatest care was taken to keep good order on board.

They succeeded so well on the river that in 1887 the General Steam Navigation Company set out to effect a similar revolution on the coast with an entirely new class. Not exactly sisters but designed on the same general principles, the Halcyon, Mavis, Oriole, Laverock and Philomel were fine little ships of their type and infinitely superior to their predecessors. Their gross tonnage varied from 470 to 643 and they were good for a steady 15 knots in any circumstances, although in some vessels the machinery was too powerful for the hull and gave a good deal of trouble. They not only improved the Thanet service, but also made it possible to open a somewhat similar run, although handicapped by its length, to the resorts on the East Anglian coast.

The success of these ships of the Navigation fleet encouraged the Victoria Steamboat Association, which had been formed to take over the river service when the Princess Alice disaster ruined her owners, to try coastal work as well. The Association inaugurated this policy in 1890 by buying the Clyde steamer Lord of the Isles. She had been built in 1877, but she was a fine ship with a fine reputation, and when she was put on the Thanet service in 1890 she immediately succeeded in attracting large numbers of passengers. Before the end of the season it was decided that she was too small for her owners’ requirements, with her gross tonnage of 466, so that they determined to sell her and get a bigger and finer vessel.

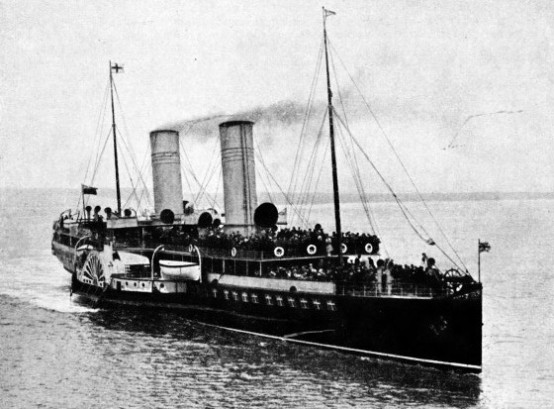

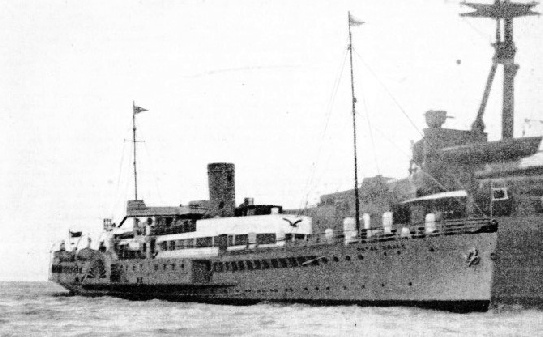

THE MODERN BUTTERFLY BOAT has the advantages of recent achievements of naval architecture, and yet retains the traditional spirit of this type of vessel. The Royal Eagle, shown here, had her hull painted creamy buff in 1935. She was built at Birkenhead in 1932 for the General Steam Navigation Company. A vessel of 1,539 tons gross, she has a length of 292 ft. 1 in., a beam of 36 ft. 8 in. and a depth of 10 ft. 6 in. Her three-

THE MODERN BUTTERFLY BOAT has the advantages of recent achievements of naval architecture, and yet retains the traditional spirit of this type of vessel. The Royal Eagle, shown here, had her hull painted creamy buff in 1935. She was built at Birkenhead in 1932 for the General Steam Navigation Company. A vessel of 1,539 tons gross, she has a length of 292 ft. 1 in., a beam of 36 ft. 8 in. and a depth of 10 ft. 6 in. Her three-

Before the Association could complete its plans a new company had started on the river. The Clacton Belle of 1890 was the first of the Belle steamers. They were built by Denny Brothers of Dumbarton, who had long specialized in fast paddle packets for the cross-

The Clacton Belle had a gross tonnage of 458 and a length of 246 feet. With her speed of 17 knots she attracted great attention. She was immediately followed by the Woolwich Belle, a little vessel of only 298 tons.

The Belle steamers opened up new possibilities on the East Coast, so that the Victoria Steamboat Association decided to put its new ship on to that run instead of competing with the General Steam Navigation Company to Thanet. She was the Koh-

Famous for Forty Years

The company, through its associate, the London and East Coast Express Steamship Service Ltd., took immediate steps to lay down a sister ship, to be named the Royal Sovereign. She was built at the same yard on almost the same plans, but was given a little more beam, which increased her gross tonnage to 891. Externally there was virtually nothing to distinguish the two ships except by their decoration and the fact that the Koh-

The Royal Sovereign did a little better than her consort on trial, averaging 19.6 knots, but on service the elder vessel proved to be the better one. She handled rather more easily and gave no trouble at all in the engine-

The owners of the Belle steamers responded to the Koh-

The Koh-

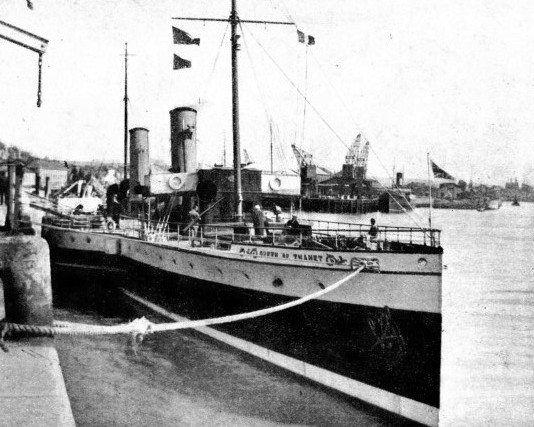

BUILT IN 1897 as the Walton Belle by Denny of Dumbarton, this vessel was bought by the New Medway Steam Packet Company for its services between Rochester, Kent, and the Thames and Thanet resorts. The Walton Belle, renamed the Essex Queen, is a vessel of 455 tons gross, with a length of 230 feet, a beam of 26 ft. 2 in. and a depth of 9 ft. 2 in. Her port of registry is London.

In 1894 the Fairfield Company made a decisive move by building the famous La Marguerite, the most noteworthy ship of the fleet for forty years. She was far more than an ordinary London pleasure steamer and resembled the finest paddle packet which had been built for service across the English Channel or to the Isle of Man. Her length was 330 feet, her beam 40 feet and she had 13 ft. 7 in. depth of hold. She had a gross tonnage of 2,205, which made her the biggest pleasure steamer in England by a large margin.

She was designed to run from Tilbury to Margate and then across the English Channel to Boulogne, Ostend or Calais. She was a magnificent ship in every way and under the command of Captain Arthur Owen made a great name for herself.

La Marguerite had scarcely been delivered when the Fairfield Company foreclosed on account of the money owing on the Koh-

The Belle Steamers Company built the Southend, Belle, 617 tons, in 1896, the Walton Belle, 455 tons, in 1897, the Yarmouth Belle, 522 tons, in 1898, and the Southwold Belle, 535 tons, in 1900. All these ships developed the same plan and made a magnificently homogeneous fleet which found favour in the eyes of many people. The old Lord of the Isles competed under various ownerships and there were one or two more or less temporary additions to the fleet.

Finally, in 1898, the General Steam Navigation Company brought out the famous Eagle, which was a great favourite and carried an immense number of passengers, her owners at that time charging a slightly lower fare than their rivals. She was 265 feet long and had a gross tonnage of 647, her engines being good for 18 knots and her appearance being characteristic, with an elliptical funnel whose top was cut parallel to the water. In her early days she had two masts permanently stepped, as in the older Navigation boats of the Halcyon type, but afterwards the mainmast was suppressed and, in the opinion of many people, her appearance was spoiled.

Meanwhile the boats on the river service had been making progress. The effect of the Princess Alice disaster was still felt seriously and, in addition, many people were kept away from the steamers because of the rowdyism on board. The vessels were exempted from a number of licensing regulations and many of them, especially on Sundays, were little more than ill-

The “A.B.C. Ships”

The Thames Steamboat Company was formed in 1897 to pick up the remnants of the Victoria Steamboat Association, and was lucky enough to secure the cooperation of Arnold Hills, the active head of the Thames Ironworks Shipyard at Blackwall. Between them they planned a new service which should be a real credit to the river and in this they succeeded well. The Thames Ironworks built the Alexandra, Boadicea and Cleopatra (the “A.B.C. ships”), which were regarded as the ideal for purely river navigation with a speed of 10 knots and comfortable accommodation. The company ran them excellently, but circumstances were adverse and it finally had to close down.

These vessels and the odd boats which ran alongside them, had done their best to keep the projected London County Council boats off the river, for their owners saw that the competition would be exceedingly formidable with almost unlimited capital behind it. They were unsuccessful, however, and after a rather stormy passage through Parliament a Bill was passed in 1904. No fewer than twenty-

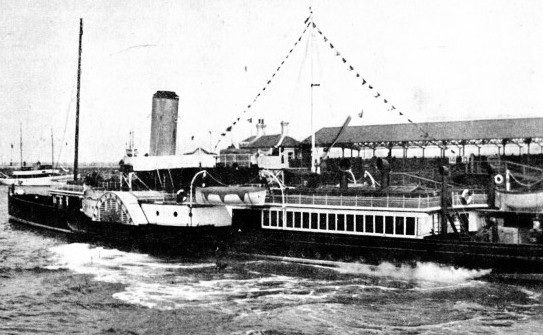

FORMERLY A MINESWEEPER built by the Admiralty during the war of 1914-

Thornycrofts built ten boats at £5,950 each, Napier and Miller ten at the same price, and the Thames Ironworks, employing local labour, were allowed to charge £6,500 apiece. Four of Thornycrofts’ boats were subcontracted to Rennies of Deptford and the fleet came into being in record time. The gross tonnage varied from 116 to 126, and all were licensed to carry 500 passengers, had an indicated horsepower of 350 and a trial speed of rather more than 13 knots. In principle, they were good little boats for their purpose, but there were minor faults in the design, particularly affecting their handiness for the difficult work of coming alongside the various piers which the Council acquired along the river banks.

The Council suffered from a lack of expert advice until Captain Arthur Owen, famous as master of the La Marguerite, took charge and made an immense difference to the boats’ efficiency. They were well kept and, as far as possible, well run; but finally the London County Council itself ruined all its chances of profitable running by building the elaborate tramways system in direct opposition to its own steamers. The vessels, therefore, had to be taken off the river and sold to run in various ports of Europe. The Thames service returned to the hands of a few small owners who had the greatest difficulty in making both ends meet.

From this period until the outbreak of war in 1914 there was comparatively little development on the coastal side. The famous La Marguerite, with the instalments for her payment long in arrears, was sold to the Liverpool and North Wales Steamship Company in the winter of 1903-

Competition to Thanet and the east coast resorts continued between the New Palace Steamers, operating the Fairfield ships, the General Steam Navigation Company and the Belle Steamers, with the occasional intervention of an outsider. All the Thanet schedules were now based on the return trip in one day, but to Yarmouth it was a whole day’s run and the boats passed one another half-

The next big step was made in 1906 when the General Steam Navigation Company went to Denny of Dumbarton, the pioneers of the turbine steamer on the Clyde and the cross-

Under the White Ensign

The paddle-

She was the first paddler on the London service to have her side plating carried to the upper deck right forward to the stem. This made her a much better sea-

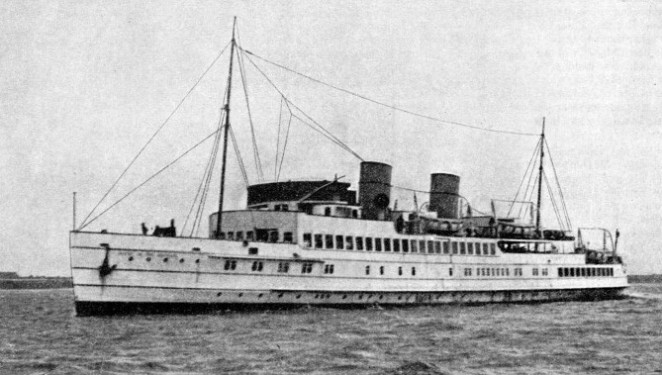

THE FIRST DIESEL SHIP IN THE EXCURSION FLEET was the Queen of the Channel, built at Dumbarton in 1935. She is driven by eight-

Then came the war of 1914-

The other ships were commissioned as minesweepers, work for which their shallow draught made them particularly well adapted.

When the service was resumed there were many changes. The Coast Development Corporation, which ran the Belle steamers, had gone into liquidation, and that fine little fleet, kept in excellent condition, was on the market. During the years which immediately followed the war these ships had many vicissitudes. The Royal Sovereign finally went to the General Steam Navigation Company for a short time before she went across to shipbreakers in Holland. The Southend Belle was sold to the owners of Clacton Pier to be renamed Laguna Belle, and the London Belle and the Clacton Belle were broken up. The remaining units of the fleet were sold to the Queen Line, the popular name of the New Medway Steam Packet Company.

From the earliest days there had been a service between the Medway and Southend. After the war the Medway Steam Packet Company was bought by Captain Shippick, an enterprising master

mariner who had practical experience in the paddle steamers running out of Weymouth as well as in deep-

The new firm was known as the New Medway Steam Packet Company. The tonnage which it took over was rather old, but the smart little Medway Queen which it built, pushing the Rochester-

Over 1,500 Tons

Eventually they joined the butterfly fleet as the Queen of Kent and the Queen of Thanet. The Walton Belle became the Essex Queen and the Yarmouth Belle the Queen of Southend. The little Woolwich Belle was already named the Queen of the South.

The ferry steamer Gertrude became the Rochester Queen for a time, and the Duchess of Kent from the Southern Railway the Clacton Queen. When the company bought the Mersey ferry steamer Royal Daffodil, which had made an undying name for herself in the St. George’s Day attack on Zeebrugge, she kept her old name.

With these additional ships the New Medway Company extended its service up-

Meanwhile the General Steam Navigation Company had not been idle. In 1924 it went to J. Samuel White and Company, of Cowes, for the paddle steamer Crested Eagle. She was the first of the butterfly boats to exceed 1,000 tons since the La Marguerite and the first to be given oil fuel, which saves the troublesome business of coaling every other night. She was built with a telescopic funnel to pass under London Bridge.

One of the latest additions to the Navigation fleet came out in 1932. In the Royal Eagle the company revived its old custom of giving their ships two masts and one funnel. This ship is a miniature liner, and her paddles and sponsons give her wonderful deck space. Although she has a gross tonnage of over 1,500, her engines have the same horse-

ONE OF THE ORIGINAL PADDLERS belonging to the Belle Steamers Company, the Southend Belle became known as the Laguna Belle when she was bought by the owners of Clacton Pier. Built in 1896, she is a vessel of 617 tons gross. She has a length of 249 feet, a beam of 30 feet, a depth of 10 feet. In 1936 she was sold to the General Steam Navigation Company and the peculiar blaze on her bow was removed.

You can read more on ”Coastal Pleasure Steamers”, “Thames Sailing Barges” and

“Romantic Sailing Coasters” on this website.