© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Handling the Sailing Ship

The days of sail are numbered and comparatively few people now understand how a sailing ship was manoeuvred. This chapter gives an outline of all the major operations of seamanship and tells how these were carried out in various circumstances

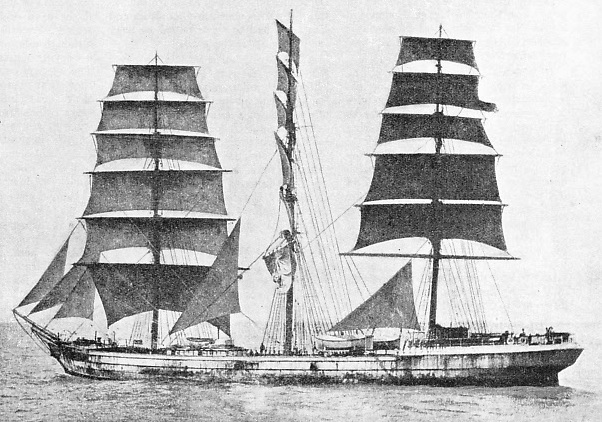

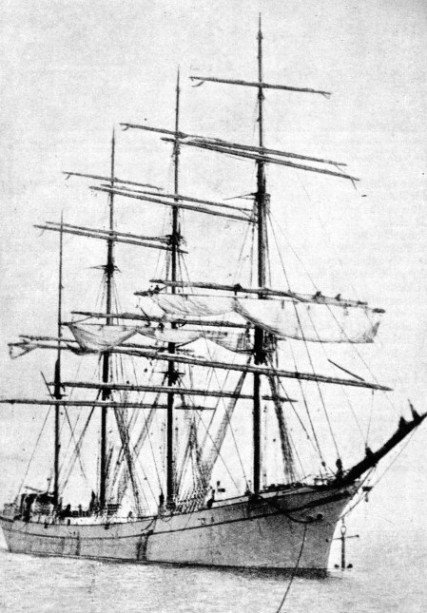

SETTING SAIL. The Barmbek, 2,277 tons gross, has been negotiating confined waters and her three courses have not been set for fear of obstructing the view from the poop. The foresail is loosed ready for setting, as also is the mizen upper topgallant sail. The main lower topgallant sail is being sheeted home Built in 1886, the Barmbek was 289 ft. 4 in. long, 42 feet in beam and 24 ft. 4 in. Deep.

THE manner m which a sailing ship was handled at sea, and reached her destination despite the direction of the wind, is a mystery to many people. The methods of handling a ship are not described in primers as are the other branches of a sailor’s craft, and the number of practical sailing-

The unexpected was always liable to happen in sail, and in the course of a voyage innumerable things might have to be done which nobody on board had ever done before and which were not laid down by any precedent. That was the real value of sail training. The youngster got accustomed to taking things as they came and to act in an emergency without hesitation and without guide.

In port the ship would be snugged down and stripped as much as possible. The great concern was for the sails. As soon as she had finished her voyage they were thoroughly dried and unbent from their yards; otherwise they would rot. For stowage in the sail locker they were always “made up” in a certain way and each sail was marked in the position laid down, so that there would be no confusion when they were taken out again. The sailor knew just where to look for the tally and a mistake was impossible. A good deal of the running rigging also came down with the sails, being coiled, tallied and stowed away, although not in the sail locker.

It was usual to “send down” the royal yards to the deck, and skysail yards if they were fitted, for this reduced the wind resistance and the topweight when the ship had got her cargo out and had not yet taken in her ballast, a time when she had to be carefully watched for stability. In the early days it was customary to send down much more and the ship in port had little left standing above her lower masts.

As a rule the sailing ship’s crew, while she was in port, was fully occupied doing any number of jobs which could not be done while she was under way. Whether they were done by a shore gang at her home port or by the crew in a foreign port of call, there were generally a fair number of things to be done aloft before she sailed again. Masts would be painted, stays white-

Before she could sail, therefore, the men had to tackle the work of bending the sails. Most ships carried three suits of sails on their voyages. The storm suit was made of the finest canvas and was the newest in the ship. The working suit was not quite up to that standard but was still good. The fine-

The squaresails were bent, or made fast, to their yards by a number of lashings at short intervals through eyelets along the head or upper edge. These lashings were called “robands”, although the sailor generally pronounced them “rovings”. In the early days the robands went right round the yard, but the clumsiness of this arrangement was obvious and for many years they were bent to an iron jackstay, which was a stout iron bar secured close to the yard.

In some ships double jackstays were fitted, the second being for the men to hold on to, but usually there was only one and they had to hold on as best they could. It was generally said that the sailor was given two hands, one for himself and one for the ship; but the ship’s duties were often so arduous, and so urgent, that he would take his chances for his own safety and use both hands on his job. Against this there were many occasions when he had to use both hands, and all his strength, to hang on to the yard.

When working on the yards, bending sails or doing any other job, the men stood on the foot-

To save time and trouble the royals, and sky sails if they were carried, were often bent to their yard on deck and sent up with it. Occasionally the topgallants were treated in the same way, but not nearly so frequently. If it were done the sail had to be cast loose as soon as the yard was in its position, technically “crossed”, to have its gear fixed ready for use. As soon as the sails were bent and fitted with their gear they were put into the neatest “harbour furl” that the crew could contrive. The foot, or lower edge, of the sail had ropes made fast to it at intervals along its length, rove through “bullseyes” in the belly of the sail and blocks on the yard, and then led down to the deck. These were the buntlines (similar lines from the side of the sail were the leechlines), and without them it would have been impossible for men working on the yard, in an awkward position, to get the heavy sail lifted up to them. Worked from the deck the job was much lighter and the foot of the sail was hauled up to the yard so that the men had to struggle with only half the depth. The sail was rolled up into the smallest compass possible, with a smooth skin of canvas outside, and was lashed to the yard by short lengths of line called gaskets. The smart crew would often put these on “man-

The fashion in furling sail changed. In the old days it was usual to “clew up to the bunt”, that is to say, the lower corners of the sail were carried in to the centre of the yard so that when the sail was furled it looked neat, tapering out to a point at the yard-

Weighing the Anchor

The time for sailing having arrived, and everything being ready for sea, the routine again depended on circumstances. If the ship was tied up to a quay she would be unmoored in almost the same way as a steamer, although she would not have so much power available to help the crew secure the ropes. If, however, she was anchored in the middle of the stream or harbour it was a much more difficult procedure. The modern ship simply turns the steam, or electric power, on to her windlass forward and heaves in the cable until the anchor breaks free and is drawn up to the hawse-

Comparatively few sailing ships were fitted with steam power, and weighing the anchor was a laborious task. In the older ships the windlass was “up and down”, and it was a back-

Comparatively few sailing ships were fitted with steam power, and weighing the anchor was a laborious task. In the older ships the windlass was “up and down”, and it was a back-

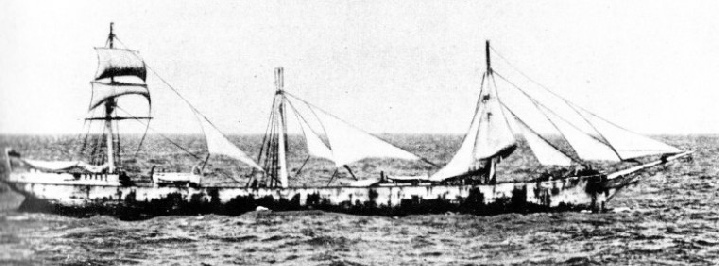

WHEN ENTERING PORT the sailing ship approached in a manner similar to that of the Cort Adelare, with her anchor ready to let go. Her main topgallant sail is clewed up, and her foresail will shortly be hauled up. Of 270 tons gross, the Cort Adelare, built in 1868, had a length of 121 ft. 9 in., a beam of 26 ft. 11 in. and a depth of 12 ft. 4 in.

Few sailing ships — only one or two of the most modern employed on training work — carried the stockless anchors, whose shanks were pulled up into the hawse-

Perhaps the greatest influence on the matter of getting under way was whether there was a tug available or not. The sailing ship could generally depend on this help in the Australian ports, although not always, but on the west coast of South America, for instance, she had to look after herself. There were many Board of Trade examiners who made a great point of this in examining ex-

Manoeuvring Out of Port

If there was no tug available, sail had to be set to a certain extent, at least, before the ship left the anchorage, and the exact routine depended to a large extent on the circumstances of the moment, especially the wind. Different captains had different ideas on most things, and as a rule they would not hesitate to alter all the gear to their taste in the course of a voyage.

In a port which the ship had to leave without a tug — generally a roadstead, for an artificial harbour or river would almost certainly have a tug service — the first necessity was to get the ship’s head in the right direction before the anchor was weighed, unless there was an unusual amount of sea room. So the ship had to be manoeuvred to get the right “cast”, for she would naturally be lying head to wind at first. That manoeuvre would be done by setting a certain amount of canvas just where its influence was wanted and, once the anchor was up, by getting her sail on as quickly as possible for steering way.

In some of the nitrate ports every ship in the harbour helped a consort to get out by lending a boat to tow her, but it was not by any means an easy job with the modern type of boat, although in the. eighteenth century the big East Indiamen were regularly towed up and down the London River

by their boats. As the outward-

Even in the ports where there was tug assistance available there were some ships which took pride in doing without it; but as modern commerce does not have much time for gestures these were generally the sail-

If a tug was avail able and was employed, sail did not need setting until the vessel had a good offing and was safely on her way. If the wind was fair, a certain amount of canvas could be set to give the tug all the help that was possible; but in this a captain had to use his judgment, for it did not want much canvas on a smart ship for her to overtake her tug. There was more than one instance of the steamboat being rammed from astern and occasionally having the dolphin striker of the sailing ship driven right through her deck and counter as it came down with a sea. With a light breeze which was not likely to suddenly strengthen a certain amount of canvas could be set with safety and this was generally done.

If a tug was avail able and was employed, sail did not need setting until the vessel had a good offing and was safely on her way. If the wind was fair, a certain amount of canvas could be set to give the tug all the help that was possible; but in this a captain had to use his judgment, for it did not want much canvas on a smart ship for her to overtake her tug. There was more than one instance of the steamboat being rammed from astern and occasionally having the dolphin striker of the sailing ship driven right through her deck and counter as it came down with a sea. With a light breeze which was not likely to suddenly strengthen a certain amount of canvas could be set with safety and this was generally done.

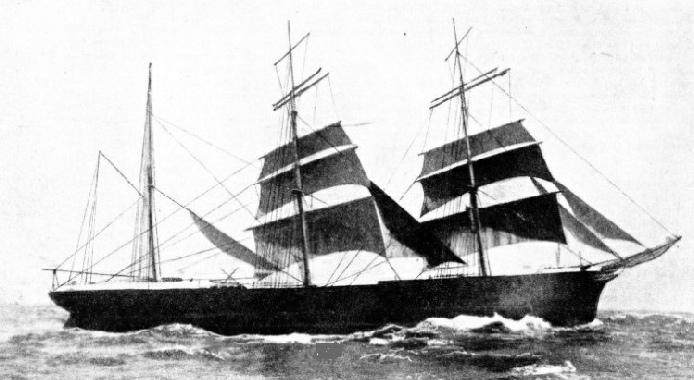

LEAVING AN OPEN ROADSTEAD under sail. The courses are set as soon as possible to get the ship under command. The Bonn is well clear of the anchorage; so the fore topgallant sail is being hoisted, and she will soon be under full sail. Built as the Samarkand in 1877 the Bonn was a vessel of 1,110 tons gross.

When she had room, and the tug was about to cast off, the business of setting sail began, although the prudent captain would not get too much canvas on to her in narrow or crowded waters. That was why the landsmen, however enthusiastic, seldom had the opportunity of seeing a sailing ship at her best. The first sails set, except with a captain who was enthusiastic on staysails and was constantly getting them up and down again, would normally be the topsails, and in the days of double topsails the lower ones were set first.

The method of setting topsails was, in broad principle, that of all the other squaresails and may be described in detail. When it was desired to set the sail, two hands, almost invariably boys, were sent aloft to cast loose the gaskets. Then the sail would immediately fall and hang flapping in big folds. The buntlines, leechlines and clewlines (from the corners) prevented its opening right out until it was wanted. The gaskets having been cast loose, the next thing was “to make them up” in a handy coil and then stop them to the jackstay with one turn of sail twine.

The greatest care was taken on this apparently minor point, for otherwise the gaskets would rest on the sail as it was bellied out in the wind and would chafe through the canvas remarkably quickly. The officers took particular care to notice that the gaskets had been made up properly and that there were no “Irish pennants” or odd ends of line left flapping, to disgrace the ship in the eyes of her consorts in the anchorage.

When the gaskets had been cast off and stopped, and the sail loosed, one of the boys generally stayed up in the sling of the yard to overhaul the buntlines as they were paid out from the deck, and to give them sufficient slack for the sail to open out conveniently When it was set he ran out a little more slack and then stopped them with twine to reduce the chafe on the canvas.

When everything was ready the buntlines, and the clewlines which held up the corners or clews of the sails to the yard-

It this chain sheet had to be hauled particularly tight for any purpose, a “handy billy”, or temporary purchase, was rigged; but as a general rule the lower topsail sheets were not touched from the beginning to the end of a voyage unless the sail had to be changed. As the lower topsail yard was always fixed to the same position on the mast by a swivel bracket, and did not have to be hoisted in the same way as many other yards, the lower topsails were little trouble to set and the fore and main were often set together.

As soon as any squaresail was set it had to be trimmed to the wind to be of real use. This was done by means of the braces which were made fast to the yard arms. When the lower topsails were set the next job was to set the upper topsails. This was a bigger task because the yards had to be hoisted into place, although there was some compensation in the sail not having to be sheeted home, because the clews were shackled permanently to the lower topsail yard-

Hoisting the upper topsail yards was one of the heaviest pulls on board ship and the usual thing was to take the halyards (originally haul-

How Sails Were Set

The amount of canvas which a ship demanded to give her steerage way and make her manageable depended entirely on the amount of wind at the moment, ft it were blowing at any strength the upper and lower topsails of the three masts the foremast and mainmast only if she were a barque, were amply sufficient to give a fair speed and keep her under control. Vessels differently rigged, four-

Now that her topsails were set, the fore topmast staysail, which would be called a foresail in a small fore-

When the foresail, the lowest squaresail on the foremast, should be set was a matter of opinion for in crowded waters it obstructed the view from the poop and it was necessary to station a look-

By the use of these tacks, which were similar to sheets but led forward instead of aft, the sail was kept trimmed to the wind. The sheet was generally carried through a sheave in the bulwark and made fast to small bitts or twin bollards on the pin rail, which was fastened inside the bulwarks and which made a rack for the belaying pins of sea fiction. The tack ran through a block on the cathead to the forward capstan.

The topgallant sails would probably be set next, in precisely the same way as the topsails, except that single topgallants, which survived at sea long after the single topsail was a rarity, combined the operations of hoisting and sheeting home. The hoist was much longer although much lighter than that of the upper topsail. This was another job that was generally helped by a shanty.

BROACHED-

Again a matter of judgment, the next sails to be set would probably be the headsails, provided that they would draw, for most captains considered them necessary to balance the sail set farther aft. At one time this idea of balance became something of an obsession, and the bowsprits and jib-

The crossjack, or mizen course, was seldom even bent as it had all the faults of the mainsail and m addition carried a disturbing draught straight down to the captain on the poop.

The cross jack (pronounced cro-

Above the topgallants the royals, which were never doubled, were set in the same way as single topgallants, and could be carried up to a fair breeze, although they had to be taken in before the heavier canvas below them. Their care was always the boys’ job on account of weight on a light yard and often only one boy had to do it. The spanker, the fore-

It was not always that all plain sail, as the sailor called the full suit without flying kites and fancy canvas, could be set with advantage, for there was always the chance of some sails blanketing the others. The best point of sailing was generally with the wind coming from about two points abaft the beam to the quarter, for then every sail was drawing well, but it was necessary to make the trim of the yards a constant care to take the greatest possible advantage of it.

“Ladies' Pocket Handkerchiefs”

In the days when sailing ships had large crews, especially in the halcyon days of the clippers, few captains were satisfied with all plain sail and there was a perfect craze for fancy canvas or flying kites. Studding sails were used as a matter of course until a careful series of observations in two of T. B. Walker’s barques on the Tasmanian trade revealed that their practical value was small, the advantage on a voyage to Australia being insufficient to compensate for the cost and trouble.

Many captains would go in for squaresails over the skysails, sails which could not possibly be of any size on account of their position and which the sailor contemptuously called “ladies’ pocket handkerchiefs”. Others were designed to catch the slightest breeze along the surface of the water; but one and all they were regarded as the sailor’s curse and they had to go when crews were cut down. It was then found that they had been of little use, and it was realized that, particularly in a fine-

Of the various points of sailing, a ship was said to be running when the wind was coming from any direction from right aft to either quarter. Originally “running before the wind” was reckoned to be when the wind was up to two points from right aft and “running free or large” beyond that. In fair weather running was the simplest, but in bad weather it could be the most dangerous of all, for steering became difficult as the stern of the ship lifted and the rudder was made ineffective. If she sheered and took charge nobody knew quite what might happen. Many a ship was destroyed through being pooped, having a heavy sea come on deck from aft, and many others survived in sadly battered condition and with men washed overboard.

THE MAIN YARDS ARE HAULED “ABACK” to take the way off a ship so that she may be boarded by a pilot or for other purposes. The wind is about six points on the port bow and the main yards are being swung square on to it. The Hero, 1,709 tons gross, was built at Port Glasgow in 1873 as the MacCallum More. She had a length of 265 ft. 4 in., a beam of 39 ft. 6 in. and a depth of 23 ft. 5 in.

If the captain let his ship run too long in a heavy sea it often became difficult and dangerous to heave her to. The only thing was to watch for an opportunity between the heaviest seas and bring her round as quickly as possible so that she lay with wind and sea on the bow, the most comfortable position. On a dark night it was impossible to see this lull.

It was not sufficient for the sailing ship to rely upon running as the ancients did in their primitive ships with one squaresail. Time meant little to them, and if the wind was not blowing in the right direction one week it probably would be the next and they quietly waited for it. It was the discovery, or perhaps the revival, of beating a ship against the prevailing wind which revolutionized shipping in the fifteenth century and permitted the discovery of new worlds. It was not easy with the ships of the period, but it was possible to get a sailing vessel to any desired port in a reasonable time, and that made all the difference to the world’s trade.

This ability was partly due to the shape of the ship and partly to trimming the yards so that the sail met the wind to the best advantage. This was done by means of braces, ropes made fast to the yard-

All the yards on a mast were never trimmed to the same angle to the keel. The lowest yard was always sharpest and the sail went up somewhat in the form of a section of a spiral. This was quite deliberate and it permitted the light sails to shiver first and to show when they were too close to the wind without running much risk. The main yard would be jammed as hard as it would go against the backstays' which were fitted with a batten, known as a Scotchman, to take the chafe of the yard.

“A Soldier's Wind”

With this ability to beat the ship a fair wind was no longer necessary. The wind coming from abeam was described as “a soldier’s wind”, fair for two ships going in opposite directions and making sailing so simple that even a soldier could master it.

Although it was impossible for a vessel depending on sails to sail straight into the wind, she could reach a destination in the direction from which the wind was coming by a series of tacks on either side of the course that she wanted to follow. By the plan of the sails and the shape of the hull the ship would move forward with the wind well before the beam. With a square-

Many laymen find it difficult to understand how a ship could make progress with the wind in that position, but it is the old law of the line of least resistance and may perhaps be illustrated by the homely example of the soap on the bathroom floor. When the soap is trodden on it does not try to push through the floor but shoots off along the line of least resistance. So it was with a ship.

UNDER REEFED TOPSAILS. The German barque Antigone has both upper topsails reefed in bad weather. Many captains would have taken in the mainsail before reefing the topsails but, as the Antigone is in ballast, her captain possibly wished to keep as many of her lower sails set as possible.

Built at Kiel Germany, in 1889 the Antigone, 1,490 tons gross, was 235 ft. 11 in. long. Her beam was 38 ft. 1 in. and her depth 21 ft. 9 in.

The closer a ship was jammed into the wind the more leeway she was bound to make, although the amount depended largely on her lines. Tacking up and down the English Channel could be a wearisome business. Three or more weeks from Dungeness to the Start was by no means unusual with all hands standing by the whole time — “calashee watches” the crew called it — and sleep snatched as might be possible. When the ship was sailing with the wind before the beam she was said to be “close hauled”, a phrase which explains itself. Generally the helmsman did not steer by the compass, although he kept his eye on it to see that the ship was maintaining something near to her compass course, but would be told “as close to the wind as you can”. Then he was required to keep the weather clew of the royal just shaking, for he knew that the other sails, with their gradually increasing angle, were getting their full value out of the wind and running no risk. “Full and by” was the order to steer with nothing shaking and “Clean full” with nothing in any risk of shaking.

Not only were shaking sails ineffective for their purpose of driving the ship along, but it was also easy to let them go beyond mere shaking and to get them taken aback, that is to say with the wind on the wrong side of them, when there was every chance of losing topmasts and gear. Particular care had to be taken to avoid shaking if men were aloft for any purpose, and many careless helmsmen have shaken sailors off the yards to be drowned or killed by falling on deck.

All the time the helmsman had to check a natural tendency of the ship to gripe, or edge too close into the wind, letting it take her aback, while the wind was always liable to change and draw ahead without warning to the man at the wheel or officer on watch. If the ship were taken aback the seriousness would depend on the strength of the wind and the condition of the fore and aft stays, for the general principle of the staying of the masts was against the strength of wind abeam and astern. Pressure from ahead was comparatively unusual. If things did begin to carry away, matters were made worse by the fact that the masts had to be stayed to one another so that the trouble generally spread from the fore to the main and from the main to the mizen.

Perhaps the most important of the ordinary operations to be carried out in a sailing ship, apart from those demanded by an emergency, was tacking, that is to say, passing the ship’s head across the wind to work an equal distance to either side of the true path that it was desired to follow. Although it was an operation that generally had to be carried out many times in the course of an ordinary voyage, there was always the chance of mishap through bad judgment.

Risks of Tacking

The great point in tacking was, if possible, to give the ship enough way to keep her under control until the operation was finished. There were two great dangers to this: first, the possibility of the wind being so light that she would not get this way; secondly, the chance of a head sea hitting her on the bow and preventing her head from completing its circuit. Then she was said to have missed stays and was in a position of grave risk in narrow waters, the hope being that she would fall off on the other tack before she was really in trouble. While the ship was in the open sea and had plenty of room, each tack or board might be a long one, for where possible the captain arranged to tack while the watch was being relieved and all hands on deck, a few minutes’ delay in getting to sleep being much better than having to be aroused. In narrow waters it was impossible to choose the time, and the ship had to be tacked when there was a risk of her going ashore if she held on.

Having the available men, the captain, for comparatively few would trust their mates to tack the ship except in an emergency, aimed at handling his yards in such a way that when the ship lost her steerage way the canvas would help to cast her head in the desired direction. The main and mizen staysails would be run down, as their handling would demand men who could not be spared and they would check her going off on the new tack. The fore topmast staysail was left, as being of great assistance in pulling the head of the ship round. Probably, but not always, the mainsail would be clewed up, lying loose in the buntlines, but the jibs would be left in position and allowed to flap until they felt the breeze and helped the fore topmast staysail in its work.

BOUND FOR RIO UNDER JURY RIG. In 1914, during a storm in the South Atlantic, the Cambrian Princess, 2,457 tons gross, was struck by a heavy sea which filled the jibs. The strain on the headstays brought down the fore topmast, which brought down the main royal mast with it. Later the main topmast and the mizen topgallant mast went over the side. With sails set wherever possible, the Cambrian Princess reached Rio de Janeiro three weeks later.

The first order was “Ready about”, which was a warning for all men to get to their stations. One or two would go to the forecastle head with the mate to handle the jib sheets, while the others were in the waist by the main braces, the second mate being on the lee brace to let go and the rest of the crowd on the weather brace to haul. The captain’s station was on the poop alongside the helmsman. His order to the man at the wheel would be “keep her clean full for stays”, which was a special caution that the sails must not be allowed to shake. The wind was then brought a little more abeam, which was an additional precaution against her losing her way. Next came the order “Hard down”, which the helmsman executed as quickly as possible, and to those on deck “Lee-

The sheets of the headsails were then let go, also the foresheet, which by tradition was the cook’s job and which was held up as an excuse for many a spoiled dinner in sail. If the vessel were a ship and not a barque, the comparatively light yards on the mizen were swung first; in any circumstances the spanker boom was brought amidships, the combined tendency being to swing her stern round. She should then have shot up into the wind rapidly, coming from seven points off the wind to about two points.

The great thing now was perfect judgment, generally born of long experience, in the right moment to give the order “Main topsail haul”, for the men to haul on all the weather main braces. If the right moment had been chosen the yards would spin round by themselves — possibly one of the most impressive sights at sea — and all the crew had to do was to gather in the slack and tauten up when the yards were nearly braced up. This self-

The ship was now in irons, and a careful watch had to lie kept by the captain to see if she gathered sternway. If so, he gave the order “Shift the helm” — which meant, put it over the opposite way, for there was no lee or weather side to put the helm up or down — to steer her under this sternway. When the wind was right ahead the jibs were sheeted to their old position, to let them push her bow off on to the new tack. If the manoeuvre were successful the sails on the mainmast would fill. As soon as this was seen the order would be “Head yards round”, and the yards on the foremast would b e treated in the same way.

First the fore tack was let go but, the sails being aback, it always meant a hard pull to get the yards round, and the cook had to lend his weight with the rest on the fore sheet. Hence the old sailor’s expression, “All hands and the cook on the fore sheet”.

The sheets of the head sails, referred to shortly as head sheets, were put over the stays and sheeted home, and the yards trimmed properly to make the most out of the wind. The braces were coiled down clear for the next move, the greatest care being taken in this coiling, as the safety of the ship might well depend on nothing jamming. The staysails and mainsail would then be re-

That was what happened when she went over satisfactorily. If she missed stays it was a different matter, and there was plenty to do. The ship would stop head to wind and refuse to go farther, either shaking everything aloft or falling back on to her old tack. It was then necessary to fill again and either make another attempt to tack or else give it up and wear ship instead. That is to say. instead of passing the ship’s bow across the wind, she was put round the other way, stern to wind. The captain always had to be ready to do this if his ship missed stays, but there were many sailing vessels, especially the big cargo carriers of later date, which could never be trusted to tack, and which always wore as a matter of course. When there was plenty of sea room it did not matter so much, but in narrow waters it could be dangerous, for the ship was bound to finish up well to leeward of the point at which she had started the manoeuvre.

Box-

In wearing and coming round with the wind the hands had to be prepared for a longer job. The captain’s idea was to trim the yards to the wind but not to let them draw to their best ability, as that could only drive the ship farther to leeward. So he shivered the sails to reduce her way, and at the same time often clewed up foresail and mainsail. The mainyards were slowly swung as she came round, while those on the foremast were left braced up until she was well off the wind. Then, after having passed the wind right aft, the foreyards were kept as nearly as possible pointing into the wind, but not aback. At the beginning of the manoeuvre the head sheets had been hauled to windward, and as she came up towards the wind all were slacked off so as not to check her swing.

In wearing and coming round with the wind the hands had to be prepared for a longer job. The captain’s idea was to trim the yards to the wind but not to let them draw to their best ability, as that could only drive the ship farther to leeward. So he shivered the sails to reduce her way, and at the same time often clewed up foresail and mainsail. The mainyards were slowly swung as she came round, while those on the foremast were left braced up until she was well off the wind. Then, after having passed the wind right aft, the foreyards were kept as nearly as possible pointing into the wind, but not aback. At the beginning of the manoeuvre the head sheets had been hauled to windward, and as she came up towards the wind all were slacked off so as not to check her swing.

DEEPLY LOADED the Port Stanley is being towed into Falmouth, Cornwall. The crew is busy stowing her sails. The Port Stanley, 2,276 tons gross, was built at Greenock in 1890. She had a length of 278 feet, a beam of 42 feet and a depth of 24 ft. 2 in.

When the ship would not tack and there was no room to wear, she had to be box-

Until now the ship has been represented as under all plain sail, but it often happened that the wind was too heavy to carry so much canvas without the risk of losing it. The spread of canvas was reduced by taking in some sails and reefing others to reduce their area. The upper staysails between the masts and the flying jib would probably be the first to go and then the royals would be taken in, “handed”, as it was usually called. This was an elementary precaution and was traditionally the boys’ job.

Starting on the weather side the sail was furled in the manner already described, but no attempt was made to give it the neat harbour stow in which a well-

It was the upper topsail only that was reefed. The lower topsail, being stretched between two standing yards, could not be reduced but had to he left entire or taken in. As the lower topsails were, with the fore-

Reefing the Sails

The general system of reef points consisted of lengths of light but strong line which passed through the sail and lay loose on either side, securely stopped where they passed through so that they could not pull out. They were all passed through the sail at the seams between the cloths where the canvas was double, and in addition there was a strengthening reef band right across the sail so that the points were really through three thicknesses of canvas. The operation of reefing started with the upper topsail yard being lowered by the halyards from the deck and helped down by means of the downhauls. The men then lay out along it, the best hand being astride the weather yardarm with the reef earing, a few fathoms of strong line, which he had taken up with him. On the leeches of the sail, at either end of the reef band, there was a reef cringle, a large eyelet through which the man on the weather yard-

To help him every man on the yard reached for the nearest reef point and “lighted” the sail up towards him, taking as much of the weight as he could. As soon as he could pass the earing through the eyebolt and the reef cringle he did so, hauled' it in, and carried it through again and again for strength before he made it fast. One corner of the sail was thus fast in some thing of a bunch to the yard and the cry was then passed along “Haul out to leeward”.

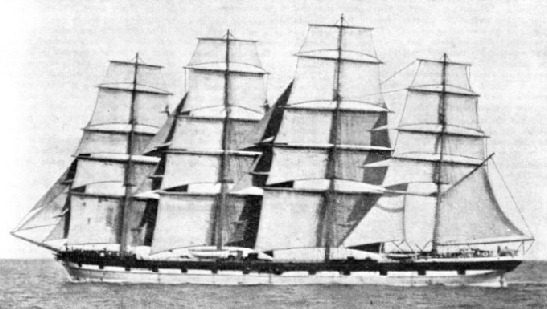

A LARGE FOUR-

Every man, who had been hauling the sail up to windward, then reversed the process and hauled on the reef points in the other direction, bringing the reef band up to the yard and stretching the sail as far as possible to leeward. The lee earing was then passed with comparatively little trouble and both ends of the sail were secured. The two ends of each reef point were then hauled up

and knotted with a reef knot on top of the yard so that the upper part of the sail was thus enclosed in a line of reef points and the area of the sail reduced. Great care had to be taken that every point was properly tied and everything was secure. The men then went off the yard and the sail was stretched taut again by means of the halyards from the deck. Shaking out reef points was the exactly opposite procedure.

Reefing the big courses was carried out on the same principle, but since the yard could not be lowered, as that of the upper topsail, the sail had to be hauled up to it by means of reef tackles from the deck. After this had been done the earings were passed and the reef points were tied in the same way.

Reefing could be a terrible task in a strong wind, and as a rule it was not attempted until there was a good force behind the gale. Then the canvas would be blown out as taut as a wooden board and it was almost impossible to get the necessary hold. Men would be fighting for hours to get in a reef and come down with every finger-

The last reduction before increasing-

As a rule it was sufficient, in the worst of wind, to keep the ship hove-

With only the lower topsails on the foremast and mainmast kept set the foreyards would be braced up as sharp as they would go and the mainyards eased in a little, the helm hard down all the time. In this way the ship kept little headway, for the helm brought her as far as possible into the wind until there was little in the main topsail while the fore topsail was full. The latter then blew her off a little and gave her enough way for the helm to take effect again and repeat the cycle. She took each successive sea on the bow where, if it was not comfortable, it was less uncomfortable and dangerous than anywhere else.

To heave a ship to for the purpose of stopping her in fair weather the main-

for the purpose of stopping her in fair weather the main-

It has been possible to give only the briefest account of some of the most usual movements of a ship under canvas.

GIVING THE SAILS A “HARBOUR FURL” as the Daylight is towed into Philadelphia. The sails are rolled as tightly as possible and lashed to the yards with gaskets. The Daylight, is a steel four-

Enough has been said to show that a sail was not merely a plain piece of canvas. Each sail had its own function for all conditions, and to get its greatest efficiency it had to be provided with much furniture of iron, rope and wire. Its total weight was thus great, especially when it was wet, for manual handling and the old sailing ships demanded a high physical standard. Many youngsters went to sea who were not up to that standard, and the wastage was terrible.

You can read more on “Rigs of Sailing Ships”, “Standard and Running Rigging” and “Training in Sail To-