© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Sea Shanties

The sea shanties which are so popular nowadays have altered in many ways since they originated in the early sailing ships to help the crews to work together. Every shanty had its own purpose, but modern machinery often obviates the necessity of singing shanties even in sailing ships

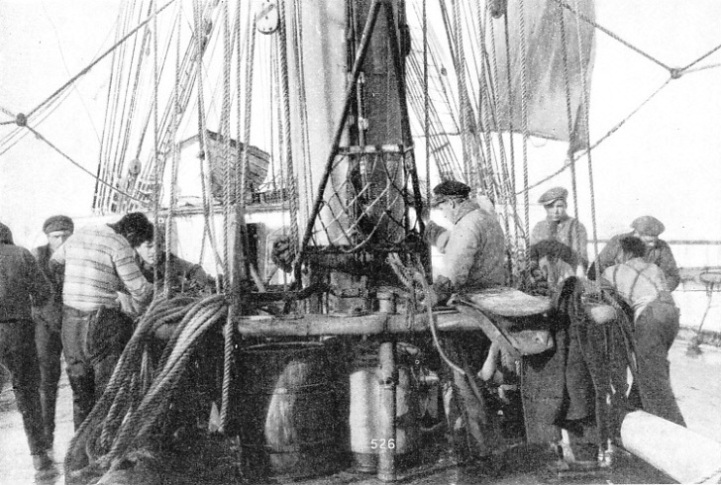

HAULING ON THE TOPSAIL HALYARDS was a heavy job, and the halyards were often taken to the capstan. Blow, My Bullies, Blow, was a favourite shanty used for this work. Sometimes the shanties went with such a swing that the officer of the watch had to be careful to sea that nothing aloft was carried away. This photograph was taken in the Grace Harwar (1,816 tons), built in 1839 at Port Glasgow. She is 266 ft 8 in long, with a beam of 39 ft 1 in, and a depth of 23 ft 6 in.

WITHIN recent years the shanties of the old sailing ships have become popular ashore. As they are sung in the drawing-

The shanties were rarely sung for a amusement. They were working songs, designed to get the last ounce of strength from a small crew. Shanties therefore had a time and rhythm of their own, designed to give the concerted pull on the rope at the right moment. They were not ballads and cannot be made into ballads with any success. It is difficult to get the proper rhythm and time unless you have a rope to pull or a capstan bar to push.

The old favourites, Shenandoah, Blow the Man Down, Billy Boy and dozens of others, are often sung at concerts and broadcasts, to the indignation of the old sailorman. They are generally sung much too fast, for the shanty was normally used only for a hard pull, and the back-

Those who have made a close study of the subject disagree about the proper spelling of the word. Should it be shanty or chanty? In the early nineteenth century they were frequently called “shanty songs” in the Gulf cotton trade.

It is held by some authorities that the name arose because shanties were sung in the drink shanties erected on the beach when a sailing ship was loading cotton. Others maintain that the word chanty is derived from the French chanter, to sing; but the British sailor would almost certainly have pronounced that word with the “c ” hard.

The shanties were sung for amusement only when the hands were ashore. In taverns, for instance, a shanty might interest the landlubbers and persuade them to slake a sailor’s shore thirst. At the sailors’ homes in the colonies they sometimes sang a shanty as they hoisted the fattest apprentice up to the roof on a line, to everybody’s amusement. In Geraldton and many other small Australian ports frequented by sailing ships it became the custom to “shanty up the curtain” at the beginning of a theatrical performance.

Rhythm was everything in a shanty, and the words, particularly those of the chorus, were of no great importance. Most of the lines had at least a measure of rhyme, and a good shantyman, greatly prized in a ship’s company, was usually apt at improvising words to suit the occasion. Although many of the shanties that were in common use were interchangeable to a certain extent, every one had its purpose in the ship’s work. Up to a point the words of most shanties varied with every ship, and the tune with every district, although they were clearly allied and recognizable.

Some of the best known shanties were kept identical wherever they were sung. John’s Gone to Hilo, for instance, had few variations no matter where the ship’s company hailed from. Rolling Home, more a song than a shanty, was regarded as sacred by the old-

A number of the old shanties have been lost entirely, although it is probable that most of them were allied to those that have survived. Many obviously originated as songs for singing ashore, but their time and rhythm were altered to suit their purpose afloat. There are few authentic versions of any shanty because of the diversities adopted in different districts, and the innumerable variations that a good shantyman brought in to suit the taste of his shipmates. Comparatively few sailors are musicians, and the difficulty of preserving the original form of the songs is therefore much the greater.

Origin of Shanties

The majority of the words concerned the sea, women, the joys of paying-

The skipper’s a curse and the mate he’s worse;

Leave her, Johnnie, leave her

was a great favourite when a poor ship was finishing her voyage and the crew had nothing more to fear. In a good ship it was seldom sung at all. The verse was the only part that was ever in any way lewd, for it was heard only by those whom it could not offend. The chorus, however, could be heard all over the ship or even all over the harbour, and the average sailor was far too decent to offend anybody’s feelings unnecessarily.

One of the most interesting points about the old shanties is the way topical allusions that had been incorporated remained for many years after people ashore had forgotten all about them.

There’s lots of gold, so I’ve been told,

On the banks of the Sacramento

is clearly reminiscent of the first Californian gold rush in 1849, yet this verse was constantly being sung in the early days of the twentieth century. One shanty, called Paddy Works on the Railway, dated from the middle of the nineteenth century when so many seamen, especially Irishmen, deserted British ships in American ports to get work on the construction of the great American transcontinental railways.

The real origin of the shanties and many other details about them are wrapped in obscurity. Probably a form of shanty has existed wherever manual labour has been employed. The Chinese coolie is an acknowledged expert, although his songs cannot be described as musical to Western ears. It is possible, too, that the Pyramids were built to the shanties of their day. One theory is that the sailor’s traditional “Yo-

The earliest, shanty of which we have any definite record is Amsterdam, or I’ll Go No More A’Roving. This can be traced back to the first part of the seventeenth century, when the Dutch port of Amsterdam was closed to British seamen. There were, however, two well-

Few shanties date further back than the early nineteenth century, when crews became smaller and the manual work proportion-

There is an enormous negro influence obvious in many of the shanties. The minor key, for instance, appealed to the coloureds and the seamen. Coloured sailors were always among the best shantymen in the ship, particularly in the part-

A good shantyman was a great asset in a sailing ship. In some of the old-

The shantyman was the only man in the forecastle who was by any chance allowed to take things easily. He would claim that he was reserving his energies for his singing and that it would not do for him to pull too hard. On the other hand, if he were the only shantyman on board, he often found himself disturbed in his watch below to help with a job on deck.

The Ship’s Musician

In halyard jobs the shantyman generally took the fore part, so that he could stand up and get more breath for his singing than the men who were bending to their work with a lead block on deck. At the pump he took the place on the bell rope next to the pump handle. He had to think of many things besides the words and the tune. When the hands were “sweating up” (giving a final tightening), he had to arrange for the chorus to be sung simultaneously with the upward roll of the ship.

In ships which were sufficiently well-

In the big ship's company of a man-

The great ambition of the ship’s musician was to be photographed sitting on the top of a capstan in action, as if he were one of the old naval ship’s fiddlers who were known as “monkey’s orphans”. This position was comfortable enough with the old-

In the Navy shantying was normally prohibited. There were plenty of men for the job and the shanty was not necessary. It might also have prevented orders from being heard. Only in small ships, or for hoisting up the biggest boats between the yardarms, was an exception made. Then only a “stamp and go” was allowed, in which the men ran along the deck with the rope to the tune of What shall we Do with the Drunken Sailor or something similar. The East Indiamen and Blackwall frigates were well manned and followed naval fashion. In many of the American sailing ships shantying was prohibited for the same reasons.

It was in British ships whose crews were cut down to the minimum that shantying was heard at its best and was most useful.

Outward bound there was comparatively little shantying in ships as they left port, but that was simply because the men were generally too drunk to do more than carry out their work mechanically. As the docks dropped astern, however, and the fumes of bad liquor were blown away, shantying occupied a good deal of the officers’ thoughts.

The second mate would sometimes begin a shanty while leading the job, but only to give a start. The officers wanted to see the men give tongue with no more encouragement than “Sing, somebody”, or “Strike a light, boys, it’s duller than an old graveyard”. If

the men took it up of their own accord, all was well; but if there was not a sound -

In the old days it was a tradition that the Norwegians, Finns and Swedes had little use for shanties; the owners were keener on brace and halyard winches and other labour-

Favourite Shanties

Even when Scandinavians were numbered in the crew of British ships it was a long time before they joined in the shanties. When after a few years they did join in, they became enthusiastic and learnt the words by heart although otherwise they were unable to speak English. Frenchmen were seldom keen on shanties, but they were always holding sing-

Every shanty had its purpose. The capstan shanties were generally the fastest, as they were almost, marching songs; but on a hard, steady pull out of the muddy bottom they often became the slowest by force of circumstances. Of the capstan shanties, a favourite was Billy Boy, originally a Northumbrian folk song. Fire Down Below, Sally Brown, Santa Anna, We’re all bound to Go were all used for work at the capstan. Rio Grande could be sung for almost any purpose and was especially popular with North East Coast ships. Weighing the anchor at the beginning of a homeward voyage was a special event that usually called for Shenandoah, Rolling Home or Goodbye, Fare Thee Well. Shenandoah was used in many circumstances. Coloured sailors sang these shanties particularly well, and the words were regarded as exempt from any variation or parody. Another favourite capstan shanty was Blow Ye Winds in the Morning, but it has practically escaped the attention of the numerous enthusiasts who have written books about shanties or set them to music.

A haul on the staysail or jib halyards was another light job that permitted a quick shanty. Most of the capstan shanties were used for this purpose and for pumping. A particular favourite for pumping was Clear the Track, let the Bulgine run. [Bulgine means engine.] The words show that this shanty originated about the middle of the 19th century.

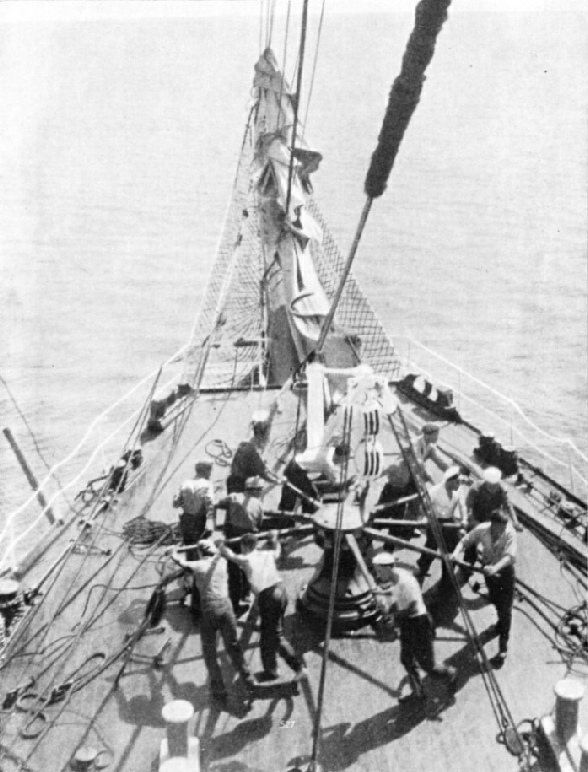

PULLING ON THE CROSSJACK BRACES, shown above, is a job that requires short strong pulls on the rope. Shanties used for this purpose are naturally less musical and have to be sharply accented. Haul away, Joe, was used for this class of work, and was sung with great emphasis on the word Joe.

Hauling on the topsail or topgallant halyards was a heavy job and demanded a shanty with a strongly accented chorus; but the halyards were often taken to the capstan and worked up with a capstan shanty. Blow, my Bully Boys, Blow, Whisky Johnnie, Blow the Man Down, Boney was a Warrior and other well-

A Long Time Ago is one of the shanties with the greatest number of variations. Old sailors can remember such different versions as There were two Ships in Callao Bay, Noah built this Wonderful Ark and A Hundred Years is a Very Long Time, but they were all the same song originally. Hauling in the sheets to a rousing shanty would often save the trouble of rigging a handy billy, which was a small tackle used for odd hauls.

The short-

“CLEAR THE TRACK, LET THE BULGINE RUN” was a shanty almost always used for pumping. The word bulgine, a nautical term for engine, dates from the middle of the nineteenth century, when many of the sea shanties originated. Neither the words nor the music was written down, and alterations were continually being made, although the original words are doubtless still preserved in some shanties. This photograph shows the crew of the Grace Harwar at the pumps.

Among the well-

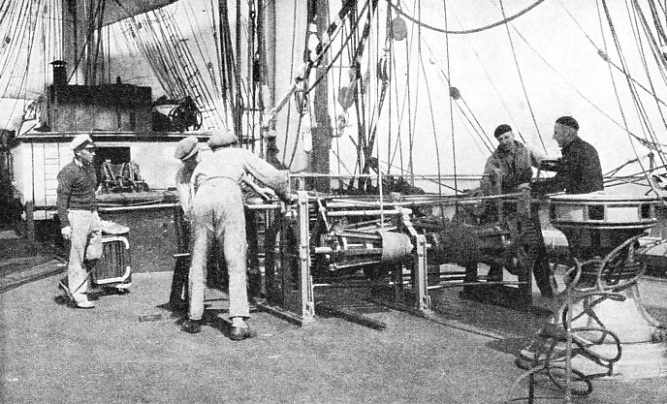

HEAVING THE CAPSTAN ROUND. The illustration shows the crew of the Penang raising the ship’s anchor by means of the capstan. Generally a fast shanty that helps the men to keep time and give a concerted pull is used, and Billy Boy was an old favourite for this reason. If the anchor was on a muddy bottom, however, a hard, steady pull was necessary, and a shanty with a slower rhythm was used. Weighing the anchor at the start of a homeward voyage was an event which usually called for Shenandoah, Rolling Home or Good-

The sailing coasters were often rather slip-

Sea shanties must not be confused with the sailors’ songs that were sung only for amusement in the dog-

Ships’ Orchestras

On the other hand these sailors’ songs were of immense use for helping to keep all hands cheerful, even when the songs were sung to order by the bo’sun’s pipe, as they were in the Navy. Many an old sailing ship man cherishes the memory of those dog-

For all their orchestras and wireless, the crack modern liners cannot put before their passengers a programme to be compared with that of the old-

The British sailing ships were not well provided with musical instruments. One or at the most two real instruments were generally the most to be expected in any forecastle, and probably one or two more in the half-

In Continental ships, particularly in those under the German, French, Italian and Spanish flags, there were some fine bands on board, able and willing to play good music, although their choice of instruments was limited by shipboard circumstances.

THE HALYARD WINCH has replaced the use of the capstan for hauling on the topsails in many sailing ships. The machine does the pulling on the ropes and the singing of a shanty will not help it to work more efficiently. The capstan is still used, however, for other purposes, and can be seen on the right of this photograph, which was taken on board the Penang.

You can read more on “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle”, “Rigs of Sailing Ships” and

“Training in Sail To-