© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Filling the Ship

This chapter explains how passengers and cargoes are booked by shipowners for their vessels, how cargo vessels may be chartered and how shipping conferences fix the charges for freight

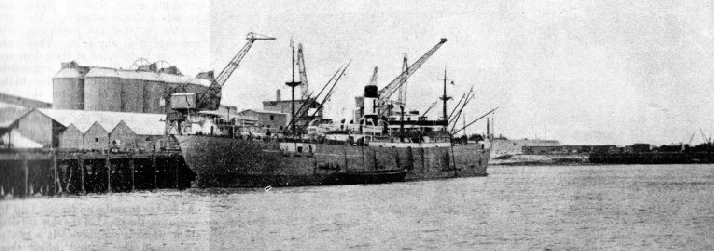

LOADING PORTLAND CEMENT from Thameside works at Northfleet (Kent), for export abroad. The vessel in the photograph is the Asphalion, 6,274 tons gross. She is 431 ft. 8 in. long, with a beam of 54 ft. 8 in. and a depth of 30 ft. I in. She was built at Greenock (Renfrewshire) in 1924. Her two steam turbines drive a single shaft through double-

BEFORE a ship is laid down, the keen owner must make a careful estimate of the probable business that will be offered during her lifetime in boom or slump. The next thing is to fill her, and even with the best of ships that is not always easy. Overseas trade and passenger business are so liable to be influenced by forces that are entirely beyond the control of the business man that there is always a big risk to be faced; but there are acknowledged ways of reducing the risk as much as possible.

These means have to be adapted to the circumstances of the moment, and the enterprising owner is ready to make any number of changes. Provided his cargo ship is suitable for more than one purpose, he may use her as a cargo liner or as a tramp, or he may let her to another owner on time or demise charter, as explained later. A passenger ship may be used on her regular service or for yachting cruises, and certain classes of accommodation may be made interchangeable according to demands.

It might appear that the most important problem is to fill the passenger accommodation of the ship. For this the designers have to start off with giving just the right balance to find favour. Magnificent public rooms are one thing, but they have to be carefully balanced with comfortable cabins. Excessive attention to the one without the other may mean that the ship loses favour, for the best advertisement that a passenger liner can obtain is the recommendation of satisfied travellers to their friends.

The owner has to make allowance for seasonal rushes on practically every trade. On the Atlantic, for instance, it is the movement of American tourists to Europe during the summer; on many Empire services the leave period of officials and officers makes an immense difference. Theatrical companies and individual entertainers passing from one seasonal centre to another have to be considered, and the many Britons who seek the sun in the winter are sometimes the most difficult of all to cater for in a really satisfactory manner. The arrangement of yachting cruises during the slack periods on the regular run is comparatively simple. The modern fashion for taking sea holidays of moderate length on one leg of a liner’s long voyage is more difficult to manage, although it is helped by the accommodation left vacant by passengers using the overland routes to save time.

To attract passengers to a ship a good deal of publicity is necessary. The best means of advertising passenger accommodation is a matter of great discussion and most companies play for safety by employing them all. Huge bills issued by the steamship companies are conspicuous on the hoardings. Most of them are effective, although some tend by their exaggeration to annoy the sailor, or the man who knows ships. They may have an absurdly small fishing smack or tug in the foreground and a bridge which would demand officers twelve or fifteen feet high, at the least, to see over its rail. The principle of the posters is varied. Some companies vote for straightforward pictures of their ships, generally in picturesque surroundings, or attractive flashes of life on board. Some prefer the futurist style.

Attractive booklets, describing not only the ships but also the places to be visited, are backed by similar booklets issued by the tourist organizations of the various countries.

Post-

All passenger-

It is even more important to fill a ship with cargo than with passengers, for it is only the crack express Atlantic liners that can run without cargo. On all other overseas services passenger ships are also cargo carriers. One of the great difficulties of the shipowner is to find a big cargo movement that coincides with his seasonal passenger rushes, so that the ships may be filled in both departments. Many a popular passenger carrier has failed financially because she could not load sufficient cargo, and numerous examples could be quoted. The cargo business is all-

There is much greater variety in the cargo carriers than in the purely passenger ships, and the business of finding cargo is therefore more complicated. First, there are the liners, running on regular schedule or “on berth”, as the shipping world calls it, either with passengers or without, and maintaining a time-

Their service is almost invariably faster, and the modern craze for speed is felt in every section. In addition, the tendency of business to-

Advantages of Cargo Liners

For quick turnover a steady trickle of small consignments is better than a whole shipload arriving periodically. So the liners have been getting the cream of the business at the expense of the tramps; but that does not mean that they have been having an easy time. The liner owner has to tackle a number of problems in filling his ship, for his expenses are practically the same whether she is full or empty.

Considering that the liner is an expensive ship to run, with overhead expenses going on every day, it might have been thought that the best policy was to cut down the number of ports of call to a minimum and to bring cargo by coaster or land transport to the ones selected. In theory that is perfectly sound; it lets the ship keep under way, reduces the extravagant time in port, improves the insurance risk (for most accidents occur close to ports), and permits a faster schedule. The only trouble is that the consignees will not have it at any price. They want their goods delivered at their door and collected from the nearest convenient dock. There has to be some limit to the number of ports of call, but the shipowner who is too drastic in his choice, attempting to get the maximum of business with the minimum of expense and delay, finds that his clients turn to his rivals.

So the owner generally has to arrange a much larger list of ports of call than he would do to suit his own purposes, and he has to make up for lost time by increasing the speed of the ship between them, which is expensive. It is easy to understand the interest which these numerous ports give to a traveller, and any number of people are now booking their passage by cargo liner instead of by passenger ship. The law allows cargo vessels to accommodate up to twelve passengers without their owners having to take out a special licence.

Most modern cargo liners are designed to carry twelve passengers. The passengers often mess with the officers and have little public rooms that are pleasant although not as elaborate as in the regular passenger vessels. Not only are these ships favoured by those who want to enjoy a sea voyage without too much society, and without being forced into bridge and deck sports for which they have no great taste, but also they are particularly useful to commercial travellers or business men inspecting their interests or calling on their clients.

Most modern cargo liners are designed to carry twelve passengers. The passengers often mess with the officers and have little public rooms that are pleasant although not as elaborate as in the regular passenger vessels. Not only are these ships favoured by those who want to enjoy a sea voyage without too much society, and without being forced into bridge and deck sports for which they have no great taste, but also they are particularly useful to commercial travellers or business men inspecting their interests or calling on their clients.

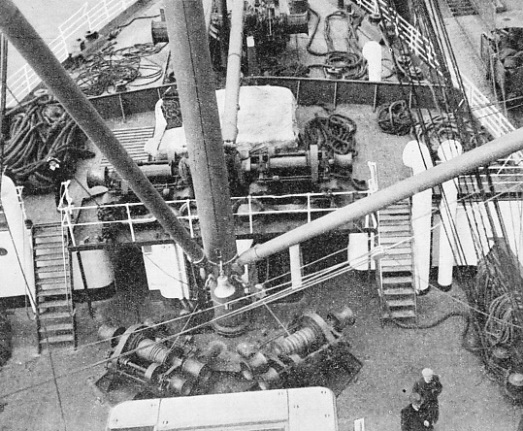

CARGO-

The schedule of a mail ship is designed for the purpose of delivering her mails, and, although these ships are generally faster, their use involves hurried visits or else staying much longer than is intended or necessary until the next ship comes along. A cargo liner, being forced to stay a number of hours in each port to handle her freight, offers the ideal facilities, and there are now a number of agents who specialize in booking passengers in such vessels, either for business or pleasure.

The time-

It is far more difficult to advertise her to the best advantage, for it is easy to waste all the money spent. Experience in the past has tended to discourage some owners from experiment. On the other hand, other owners have found it profitable, and such events as the “Wool Derby”, when some of the fastest cargo liners in the world race home from Australia with the first of the new season’s clip, are beginning to excite the same interest as did the races between the old tea clippers. Up to now, however, the greater part of this interest, and the benefit accruing from it, has been on the Continent rather than in Great Britain.

In the same way as the owner of the passenger ship, the cargo vessel’s owner collects a certain amount of business by the efforts of his own staff and by arrangements through his office, for which reason he publishes sailing lists.

There is periodically a cry throughout the business world that the middleman should be abolished and profits go direct. A number of the big shipping groups have tried to do without the broker altogether and have worked up their own big departments for doing his work. But they have all found that the advantage is more theoretical than real, and almost without exception they have been forced to admit that the agency system has great advantages despite its cost. For one thing, there is the added spur of competition, and shipping agents as a class are among the keenest business men to be found anywhere. Most people who have a certain amount of cargo to dispatch will go to an agent. The agents are paid on a carefully graduated scale drawn up by the Institute of Chartered Shipbrokers in consultation with the Chamber of Shipping. Although it is often complained that these charges are high, they do not appear to be so when we consider the work that is done for them.

Judicious Stowage

Sometimes this work is limited to arranging the carriage of cargo, but often it goes much farther and the broker not only acts as the agent for the ship in port, transacting all the complicated business which is necessary, but can also look after the interest of the shipowner with a specialist knowledge that is not likely to be possessed by the outsider. Modern shipbrokers fulfil so many functions that it is necessary for them to have a high standing and solid financial foundation, for their work at either end of the voyage is arduous and complicated.

When the shipowner has secured the business, either by his own efforts or through a broker, his next problem is to fill his ship to the best advantage. The judicious stowage of a general cargo is one of the most difficult matters connected with shipping and it always demands wide experience. It is not sufficient to get the freight through the hatches of the ship. It has to be carefully adjusted, or the ship will be full before she is down to her load line; or on the other hand she may be brought down to her load line before she is full. With some cargoes this cannot be avoided, but in any circumstances it is a waste, and every shipowner does his best to mix the commodities in such a way that she is carrying the greatest possible amount by either standard.

The cargo, generally running into an enormous number of different items, has to be carefully arranged on board. Certain cargoes, for instance foodstuffs in refrigerated spaces, can be accommodated in one place only. Even so, there are often many things to be considered for their safe carriage. The ordinary general cargo has to be distributed through the holds and ’tween decks with the greatest possible care.

THE POOL OF LONDON is a centre of the shipping industry. Not far away are the offices of many great shipping companies. This photograph shows the Groningen, a British vessel of 1,205 tons gross. She is 245 ft. 6 in. long, with a beam of 40 ft. 1 in. and a depth of 12 ft. 9 in.

The first consideration is that it must be easily handled at the intermediate ports of call. The cargo that has to be discharged there must be handy to the hatches so that it may be taken out without disturbing a lot of other consignments, lifting them out on deck or on to the quayside and putting them back again. Similarly, the parcels shipped at the intermediate calls must be stowed in such a way that they do not interfere with the handling of those parcels which are already in.

It is important to maintain the advertised schedule, for being held up at the port while cargo is being landed and shipped is fatal to a vessel’s reputation. These, however, are not the only considerations. The ship’s stability is all-

Another factor which has to be constantly in the mind of the shipowner is that he may suffer from claims caused by cargo crushed by other parcels, contaminated by certain commodities being stowed next to others with which they do not agree, or damaged by damp through faulty ventilation and a thousand other reasons. The possibility is covered by insurance, and the experienced shipowner realizes that the underwriter is in business for profit and that a bad reputation will soon send up rates of premium and affect the ship in other ways.

In many companies, especially on the Continent, a premium to the officers when a cargo is delivered without any claim makes a big difference and keeps them keyed up to a high pitch. This system is seldom adopted by British owners, although it has much in its favour. The plea that the safe delivery of cargo is part of an officer’s duty, and should therefore be attended to without any premium, loses sight of the fact that it involves an immense amount of extra trouble to an officer who is already fully occupied, and for this no overtime is paid. A trip in one of the Dutch liners on the East Indian run, for instance, will speedily show the observer the immense amount of extra work shouldered by the officers under this system.

Regulating Rates

Although he is at liberty to make his ship as attractive as he can, the owner of almost every cargo or passenger liner is controlled to a certain extent by the various conferences to which he belongs for his own protection.

Conferences of some sort have been in existence since the heyday of the Hanseatic League and the Italian republics -

The shipper who thinks it is hard that he should not be allowed to take advantage of periodical slumps to quote a ridiculously low figure should remember that he is also protected from freights soaring under the influence of some outside event, for it takes a considerable time for the conference to make a readjustment. He should also remember the immense benefit that he gets from services which are maintained under conference rules when times are bad as well as when they are good. Without the control, the owner would naturally take the first opportunity of withdrawing a ship that was not paying her way and the shipper would suffer.

Every conference breaks up periodically and there is a spell of rate-

On principle the conference allows the keenest competition between its members except by cutting rates. In the passenger trade the conferences periodically give every ship her rating according to what she offers the passenger in the way of size, speed and luxury. In the cargo business they are concerned with fixing a reasonable rate and preventing cut-

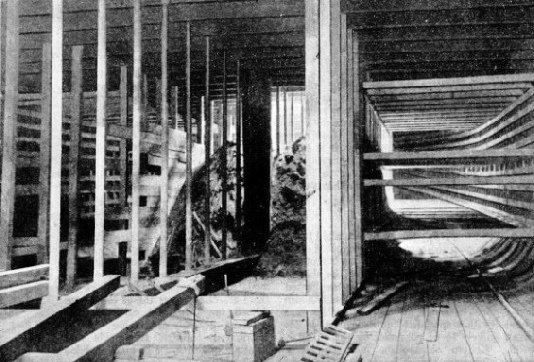

SULPHIDE OF LEAD ORE must be carefully stowed so as not to upset the vessel’s trim. The cargo shown here was shipped in the Spencer Gulf, South Australia, by the sailing ship Robert Duncan, 2,135 tons gross. This ore is so heavy that 11.7 cubic feet weigh one ton. A strong timber structure had to be built to prevent the ore from distributing itself over the hold. The Robert Duncan, built in 1891, was renamed the William T. Lewis and used as a barge in British Columbia.

Naturally the conferences must take measures to protect themselves. Otherwise many shippers would favour them when they were running their services at a loss in times of slump and immediately turn to the conference breakers as soon as things were paying again. The most satisfactory and effective method of doing this is by what are called deferred rebates. These generally amount to about ten per cent of the freight paid, and they are returned to the shipper after four or six months provided he has employed only the conference lines in the meantime. This system of deferred rebates has been attacked time and again, but it has

fully justified itself before committees of inquiry and is now generally admitted to be the only means of getting fair treatment for the companies.

On the other hand the tramp owner who wishes to fill his ship is virtually without restriction. The only checks on price-

The chartering of a tramp steamer is a complicated business. A tramp does not sail to regular time-

The charter parties for such voyages contain infinite possibilities of unsuspected trouble and the tramp owner -

There are three ways of chartering ships, two of them applying to liners and tramps alike, and the third to tramps only. The time charter and the demise charter apply to ships of all types and permit the owner to make up any deficiency in his own fleet. Nearly all charters are based on the deadweight capacity of the ship and not on her gross or net tonnage.

A shipowner who has the chance of a big consignment of profitable cargo for which he has no suitable ship will take up such a vessel on time charter or demise charter according to circumstances. The owner who lets such a ship can demand guarantees for the whole sum that can be owing, but this is not done with firms of good standing and repute. The Documentary Committee of the Chamber of Shipping in London arranges the drafting of standardized charters which greatly reduce the chance of friction or loss to those concerned.

In a demise charter the charterers become virtually the owners of the ship for the time specified. They receive the ship, after which they supply the crew and pay all expenses and liabilities. The only restriction is that she must be redelivered in the specified time in the condition in which she was taken over, fair wear and tear excepted. As the charterers under a demise charter undertake so much responsibility, the rate is generally much lower than under an ordinary time charter.

Time, Demise and Voyage Charters

In a time charter the owner pays for all provisions, wages, insurance, stores and fees connected with shipping and discharging the crew. The charterer pays for coals (excluding those used in the galley), port charges, pilot dues, agents’ commissions and the like. The consular charges are divided, those on the cargo going to the charterers and those on the crew going to the owners.

In arranging a time charter the cargo that is to be carried and the area of operations are quoted to give owners fair warning of undue dangers to which their ships may be subjected. The owner naturally has to take precautions to prevent his ship from being abused or strained. The period is always quoted as “about”, to make a fair allowance for a natural difficulty in the exact date of delivery, but loss of service through accident, breakdown or deficiency in stores stops the payment to the owner after twenty-

Demise and time charters are not by any means unusual, but they are not nearly as frequent as the third type. The voyage charter is the everyday business of the tramp. It puts the ship at the disposal of the charterer for the carriage of a specified cargo between specified ports, and payment is fixed on the quantity of cargo that the charterer wishes to ship.

As it can seldom be possible for him to get a ship of exactly the right tonnage, some sacrifice has to be made by a vessel which is rather bigger. In the charter party the correct description of the ship and of the cargo which she is to carry have to be given, and the ports or voyage are specially quoted “or as near thereto as she can safely get”. The weight or measurement of the cargo that she undertakes to transport is qualified by the words, “but no more than she can reasonably stow and carry”.

All the loading expenses and port charges are the concern of the owner, but an arrangement has to be made for the time spent in port. The time allowed for the ship to load or discharge is known as “lay days”, and they begin when the ship is ready and able to start operations. After these days have expired, if the work is not finished, the charterers have to pay the owners so much a day “demurrage” to compensate for the lost time. In special circumstances this demurrage may be waived, but it usually requires law courts to decide what these circumstances are. On the other side the owners will allow the charterers “dispatch money” when the lay days are not used up.

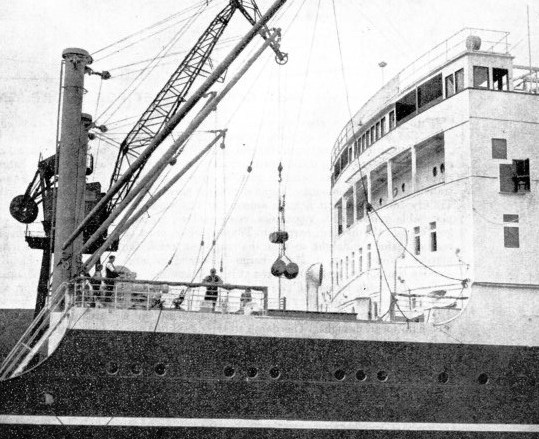

FOR EXPORT TO INDIA. Barrels of cement being loaded at the Royal Docks System in the Port of London. This system consists of the Royal Victoria Dock, the Albert Dock and the King George V Dock. The vessel illustrated is the Brocklebank steamship Mahseer. Built in 1925, she is 470 ft. 2 in. long, with a beam of 62 ft. 2 in. and a depth of 32 ft. 5 in.

You can read more on “Handling the Overseas Mail”, “London’s Link With the Sea” and “Romance of the Trade Routes” on this website.

You can read more on “How Grain Cargoes are Handled” in Wonders of World Engineering