© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Battle of the Dardanelles

No historic naval engagement did so much to prove Admiral Mahan’s contention that “ships are unequally matched against forts” as the action in the Dardanelles on March 18, 1915

DECISIVE NAVAL ACTIONS - 8

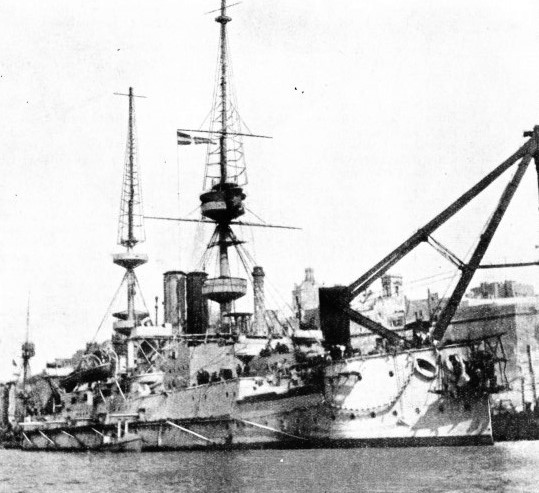

A BATTLESHIP IN ACTION on March 18, 1915, in the Dardanelles. This remarkable photograph, taken from the French battleship Gaulois, shows H.M.S. Prince George (also illustrated below) under fire from Turkish 5.9-

THE tremendous naval effort which was made in 1915 in the Dardanelles, the narrow waters separating Europe from Asia, will never fail to fascinate human imagination. Whether we consider that terrible day as a thrilling drama, as a wild gamble with fate, or as a brilliant failure, it was one of those historic occasions when the world’s future development remained dangling in critical suspense. To-

This, at the time, was clearly understood by the Germans. “If the Dardanelles fall,” wrote Grand Admiral von Tirpitz, “then the whole of the Balkans will be let loose on us”. It was this same distinguished flag-

The failure of that day, March 18, 1915, committed Great Britain to an amphibious campaign of such magnitude that an unbearable strain was imposed on Navy and Army alike. From northern Europe thereafter had to be dispatched countless men-

By a curious sequence of events the whole story centres round the German battle cruiser Goeben, which is unquestionably the most historic vessel that survived the war of 1914-

Having arrived off Constantinople, she lay in the Bosporus opposite the German Embassy, and at night she was a blaze of brilliance. In accordance with the German Emperor’s wishes, her Admiral Souchon entertained considerably on board, and among his guests was Djemal Pasha, Turkey’s Minister of Marine. Souchon, besides being an extremely able naval officer, was a natural diplomatist and first-

In June 1914 Germany had in the Mediterranean only one other warship, the light cruiser Breslau, 4,478 tons, built in 1912 and armed with twelve 4.1-

Next day the international situation, following the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, looked threatening, and on August 2 Admiral Souchon brought his two ships into Messina, Sicily, where they coaled to full capacity, in spite of Italian protests. They left again at 1 a.m. of August 3 bound west at 17 knots with lights out, to cut the Algeria-

The two vessels then steamed eastward, but meanwhile at 2.35 a.m. on that same August 4, a wireless message from the Nauen radio station informed Souchon that Germany had made an alliance with Turkey on August 2. The Goeben and the Breslau were to steer for the Dardanelles. This meant steaming another 1,500 miles, so that Souchon again had to head for Messina and fill up with coal. On the way he was intercepted and followed for part of August 4 by the two British battle cruisers Indomitable and Indefatigable. Not until midnight was war declared between Great Britain and Germany, so the Goeben and the Breslau safely reached Messina early the next morning. Once more they fuelled, and at 5 p.m. on August 6 they finally set out from Sicily.

On the night of August 10 they entered the Sea of Marmara. Then was quickly manifested the effect of those previous two years during which German diplomats, and German naval and military officers, had been tactfully scheming.

The sight of these two fine ships, and the anxiety of Germany to sell them, stirred the Turkish Government, which was in a perfect mood to become buyer, because it had just been deprived of the battleship Reshadieh and another dreadnought that were approaching completion in England. On the outbreak of hostilities the British Government had requisitioned both, which eventually joined the Grand Fleet as the Erin and the Agincourt respectively. While this transference to the Royal Navy was justifiable and even inevitable, it created in Constantinople a keen disappointment and a strong anti-

The Fatal Error

Great Britain demanded that the German personnel be dismissed. About 3,800 more Germans, however, arrived in Constantinople by train, chiefly for manning Turkish destroyers, giving instruction and doing repair work. At the end of October the Goeben, with the light cruiser Hamidieh and two Turkish destroyers, bombarded Sevastopol as well as Odessa and Theodosia, while the Breslau wrecked the petroleum tanks of Novorossiisk. After this Black Sea incursion, Russia declared war against Turkey, the Allies’ Ambassadors on November 1 left Constantinople, and the British squadron watching the Dardanelles was ordered to bombard the outer forts at the first opportunity.

Thus Souchon’s two ships committed Turkey to a serious struggle, involving the British and French in a most difficult task. Unfortunately, too, the Allies made the fatal error of ignoring the elements of naval strategy as enunciated by long eras of history. “Ships are unequally matched against forts ... A ship can no more stand up against a fort costing the same money than the fort could run a race with the ship”. So summed up Admiral Mahan, years before, in his authoritative volume on Naval Strategy. Yet in defiance of this principle there now began an unscientific piecemeal procedure in the hope that ships’ guns might first reduce the outer Dardanelles forts, then overcome the intermediate defences, finally conquering the defences at the Chanak Narrows and bursting a passage through to Constantinople.

In spite of no little gallantry and the expenditure of shells, time soon proved Mahan was right that “ships are unequally matched against forts”. The destruction of forts was a land job for soldiers, who would also have the duty of holding these defences not merely for the fleet to steam through the Straits but also for the supply ships to come along with food, stores, munitions and fuel. Unless these commanding shore guns were kept silent, the Allies’ Fleet after having reached Constantinople would be starved into surrender.

A “COW-

It was on February 19 at 7.58 a.m. that the first shot was fired from the Turkish battery (Orkanieh) on the southern side of the Dardanelles entrance. That day certainly witnessed a memorable display of naval strength. The British Vice-

In spite of all the shells fired against the Straits’ outer forts, however, the net result that day was slight. The ships had failed to dominate the land defences, and the most which could be claimed was that earthworks had been turned into rubble and dust. The enemy’s gunners had been driven temporarily away from their guns into shelter, but the weapons themselves could not be silenced permanently. The painful conclusion began to display itself all too clearly. The Navy unaided could not get through the Straits.

On Thursday, February 25, long-

The great dilemma might thus be summed up easily. The mines could not be swept away because they were protected by enemy guns, and battleships could not get within close range of the guns by reason of the minefields. More and more obvious did it appear that the Dardanelles operations could not continue without military assistance.

Ships Attack Forts

We cannot help sympathizing with Admiral Carden for being placed in a most difficult position. The strain, the worries and the disappointments overcame him, so that two days before the appointed date for the attack he went sick, gave up his command, left for Malta, and was succeeded by Admiral de Robeck, who thus suddenly received an unenviable legacy.

At 8.30 on the morning of March 18 the fleet left its base with a light southerly wind, and two hours later the first line of British bombarding ships proceeded up the Straits. This first division comprised the Queen Elizabeth, Agamemnon, Lord Nelson and Inflexible, ahead of which steamed destroyers fitted with light sweeps for clearing the immediate vicinity of mines. At about 15,000 yards from the Narrows they took up their respective positions in the above order from north to south, with H.M.S. Prince George guarding their northern flank from the enemy’s field guns, and H.M.S. Triumph guarding the south. The four French battleships were ready to close the forts as soon as opportunity offered.

These French ships, the Suffren, Bouvet, Gaulois and Charlemagne, under Admiral Guepratte, were to approach to 10,000 yards from the Narrows, and at a given signal were to be relieved by H.M.S. Ocean, Irresistible, Albion and Vengeance, supported by the Swiftsure and the Majestic. By a series of terrific bombardments the enemy’s men were to be driven away from their guns, the main forts temporarily dominated and the light batteries controlled. Three pairs of trawlers (protected by the Cornwallis and the Canopus) were next to sweep along the Asiatic shore, and the fleet would then advance with murderous fire against the Narrows at close range.

That was the plan, but at 10.58 a.m. the Turko-

A 6-

Before 11.30 the Queen Elizabeth began her onslaught. Her first two shots fell into Chanak town. Soon she got on to her allotted fort, causing a large fire and explosion. The enemy was replying with slow determination, for the reason that his shortage of ammunition necessitated economy. Not so, however, the howitzers on either side of the Straits which straddled the Lord Nelson at

noon, and still sent dozens of shells whizzing near the other ships.

Then the British admiral signalled the French vessels to enter the battle, whereupon the Turkish forts fired with a new vigour and quickly got the range. The Queen Elizabeth was hit three times, and at 12.30 the Gaulois was so badly damaged by a 14-

Viewed from the forts, the situation at this time seemed seriously menacing, and the Turks believed the ten Anglo-

So the battle reached a rare intensity. Especially against the Inflexible, stationed on the Asiatic side, did the powerful forts now concentrate their anger. So also the Eren Keui howitzers gave her no peace. For this special attention there was a notable reason that was hidden from all British knowledge at the time. One night, some ten days before, a small Turkish steamer of 380 tons, named the Nusrat, built in Germany the previous year, had dropped down from Chanak with the current under the dark cliffs of the Asiatic side till she came abreast of Eren Keui Bay.

On board her were twenty mines, and Colonel Geehl, the Turks’ mine expert. He now laid these dangerous “eggs” not athwart stream but in a line with the current, the eastern end being about 11,000 yards from the Narrows, and the western limit being 14,000. This danger area of 3,000 yards was for the purpose of trapping one of the bombarding battleships which were wont to use that area. For this reason the mines were set to a depth of not less than 15 feet. A trawler or destroyer drawing 12 or 13 feet of water might pass over with impunity and not expose the ambush by being blown up, but a deep-

Wounded Officer's Heroism

This projectile struck the Inflexible’s fore signal-

Commander Verner, in spite of his sufferings, carried on giving orders as if unhurt. Verner raised himself to the level of a voice-

At once the Fleet-

With no little pluck the Inflexible’s second-

Captain Phillimore, because of the conflagration, had dropped back about a mile, but now went into action again after the flames had been extinguished and at 2.36 was heavily engaged. Matters were lively and fast working up to a climax. Just before 1 p.m. H.M.S. Agamemnon had been hit by three shells simultaneously, and her after funnel, on being struck, opened out as if it was a lotus. By 2 p.m. she had been struck a dozen times below her armour, five times on the armour, and seven times above.

ONE OF THE BOMBARDING BATTLE-

Admiral de Robeck now called up his six minesweepers to prepare a way for further advance. Barely had these trawlers begun their perilous task than howitzers and field batteries shelled them so fiercely that this operation had to be cancelled. At 2 o’clock H.M.S. Ocean, Irresistible, Albion, Vengeance, Swiftsure and Majestic were ordered in to relieve the French squadron, and then began the most tragic period of a great tragedy. The French squadron, making its withdrawal, passed too far in the direction of the Asiatic shore, and with amazing suddenness the Bouvet (leading the line) struck one of the Nusrat’s mines. Almost before human understanding could realize what had happened she was bottom uppermost, in a cloud of smoke, still going ahead.

In a period of only 2 minutes 35 seconds the Bouvet came steaming at full speed, hit the unseen danger, capsized, and began to disappear. Two picket-

H.M.S. Triumph, which had been steaming just astern of the Bouvet, only just escaped a similar fate. The Lord Nelson narrowly evaded a mine that came floating past with the current, and at 3.32 the Irresistible either struck another mine or received injuries from a shell below the water-

Disaster Follows Disaster

This explosion, which was extremely loud, seemed to lift the ship bodily and make her quiver fore and aft. She then listed over to starboard, out went the lights, and the pitch darkness was accompanied by a sudden strange silence. When oil lamps were lit, it was found that the engines were still running smoothly, every man below remained at his job, and the most perfect engine-

The Inflexible was now in a most serious condition, settling down by the head. She seemed destined to share the Bouvet's fate. Some 2,000 tons of water had poured in, and thirty-

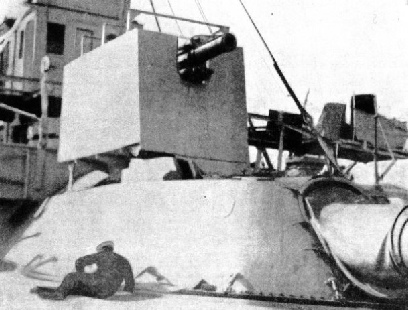

SANDBAGS WERE USED TO PROTECT THE BOAT DECK of battleships against shells from the Turkish howitzers on either side of the Dardanelles. Despite this and other precautions, however, the battle of the Dardanelles was to prove the truth of Admiral Mahan’s contention that even the most heavily armed ships were no match for forts.

Although the Inflexible had been compelled to retreat, the battle within the Straits still waged furiously and disaster followed disaster. The Irresistible at 3.32 had suddenly developed a list, caused either by a mine or a shell. She had certainly also been severely injured by a shell from Fort 19 (Hamidieh I). After having got within 10,000 yards of Fort Rumili Medjidieh. she had turned towards the Asiatic shore, being about to lengthen the range; but at 4.15 while she was drifting with engines stopped off Eren Keui Bay, she struck the northernmost end of the Nusrat minefield and was holed underneath her starboard engine-

Through this galling fire the destroyer Wear bravely steamed alongside and rescued 582 men and twenty-

Abandoned Battleships

Into this terrible scene dashed the three destroyers Colne, Jed and Chelmer and took off survivors, though the Chelmer was hit in the boiler-

Imagine this pair of armoured vessels, displacing respectively 15,000 and 13,000 tons, cruising about on their own with not a living soul on board. Ghost ships, they drifted with Ensigns still flying, but at the mercy of current and whirling eddies — great masses of steel without guiding hands, lost and helpless. Years of valuable service and long cruises over the globe had suddenly ended. Engines had stopped for the last time, guns would never bark again, cabins and wardrooms would never hear any more the sound of human voices. Black night and doom had settled down over decks that once had been spotless. All the pride and care expended over two big fighting units now had come to an end. For a while the pair continued in a mad but brief career. Sometimes they circled about in the darkness and under the shadow of the land between Europe and Asia, until enemy searchlights picked them up again and presented them as ideal targets for the shore guns. Ultimately the battered hulls were swallowed up by the leaden waters.

It had been a most unhappy Sunday for the Allies, but a day of deliverance to the enemy. True, the forts and town of Chanak had been left in flames, but that was not to say that the Narrows had been passed and the passage towards Constantinople begun. De Robeck’s force, which had the appearance of such might and power, was never less than six miles from the Narrows and did not arrive within two miles of the main minefield’s limit, where no fewer than 375 explosive “eggs” awaited them in ten lines. On the other hand the Admiral had lost three of his sixteen capital ships.

and three others had been put out of action.

The forts were never destroyed, in spite of all the vast expenditure of Anglo-

Never again did the Fleet attempt the folly of trying to break through unaided. Never again during that campaign did the Turks have cause for so much elation. To them March 18 seemed the day of decisive victory, a day to be commemorated, for they had been delivered from the hands of the invaders.

Still, wonderful to relate, the much battered Inflexible lived to have her revenge. They patched her up at Tenedos. After further repairs at Mudros and Malta she was completely overhauled at Gibraltar. Less than a year later she took part in the battle of Jutland.

Still, wonderful to relate, the much battered Inflexible lived to have her revenge. They patched her up at Tenedos. After further repairs at Mudros and Malta she was completely overhauled at Gibraltar. Less than a year later she took part in the battle of Jutland.

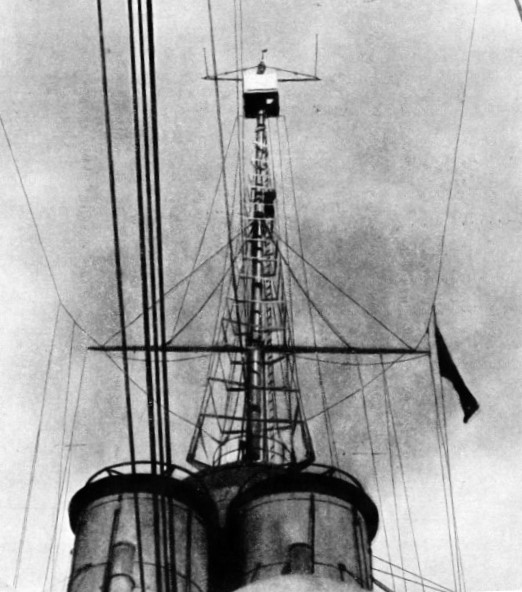

THE CROW’S NEST of H.M.S. Prince George was specially erected to facilitate observation of fire during the Dardanelles action. The “snaking” round the rigging of the mast was designed to make it appear less defined, and thus to thwart the Turkish gunnery.

You can read more on “Battle of the Falklands”, “Battleships and Cruisers” and “Big Guns in Action” on this website.