One of the most famous of the Q-ships, though one of the smallest, the coaster Penshurst had a brilliant record of successes before she was lost in an engagement with an enemy submarines

MYSTERY SHIP ADVENTURES - 5

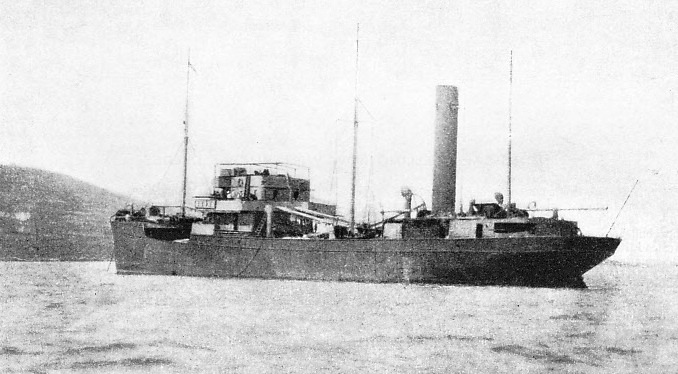

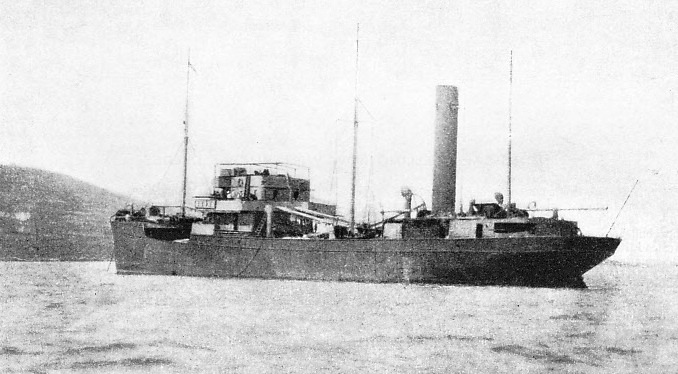

A SUCCESSFUL TRAP-SHIP, the coaster Penshurst, 1,191 tons, commanded by Captain F. H. Grenfell, R.N. accounted for UB 19 on November 30, 1916, in the English Channel. The commander of the German submarine had been deceived by the tactics of the “panic party” and was only 250 yards away when the Penshurst opened fire. In ten minutes the U-boat was sunk.

ON November 29, 1916, one of the smallest ships that took part in the war of 1914-18 began the first of a series of adventures that was to make her the envy of many a genuine warship.

The vessel was the Q-ship Penshurst, a small 1,191-tons coaster, commanded by Captain F. H. Grenfell, R.N. For a year she had been in the English Channel wondering when her great day would arrive.

On the morning of November 29, the Penshurst was steaming at 8 knots to the south-west from a position south of Start Point, Devon. The sea was smooth, the wind light from south-west, the sun just rising, the time 7.45. At 4.30 on the previous afternoon a submarine had been reported in the neighbourhood of Start Point, and the sailing vessel Lady of the Lake had been sunk that day, thirty-five miles south-east of the Start. Seven miles away coming towards the Penshurst was a British steamer of 2,500 tons; hull down on the decoy’s starboard bow could be seen a sailing ship coming up Channel; no other vessel was visible. The alert look-out, however, noticed a small object on the port beam. The glare on the eastern horizon made it difficult to define either the nature or the distance of the object, but at 7.52 a.m. every doubt was dispelled when there came the flash of a gun — from a submarine.

The first shell dropped sixty yards short, but the second passed over the Penshurst’s mainmast. The range was five miles, but the light so bad that Captain Grenfell could not see if the submarine was approaching. To lure the German nearer, the Penshurst altered course at 8 a.m. to the north-west and slowed down. By that time the sun had risen above the horizon, though the light was still bad. Moreover, the submarine, having spotted the 2,500-tons steamer (whose name was the Wileysike), had altered course to cut her off, doubtless intending to sink her first and then deal with the smaller steamer afterwards. Captain Grenfell again altered course so as to cross the submarine’s course at right angles, and the German fired his third shot, which fell 200 yards short of the Penshurst.

It was now time for some of the Penshurst’s crew to carry out the pretended abandonment and “panic”. Boats were being turned out and lowered with all possible clumsiness, to waste time, enabling the submarine to get within 3,000 yards and turn on a course parallel with the Q-ship. At 8.20 the German was just abaft the port beam, silhouetted against the sun’s glare, three hands standing in the conning-tower. He was cautious, however, and refused to come any nearer. Captain Grenfell had to open fire or be shelled.

The Penshurst loosed off two rounds from the 12-pounder and 6-pounder guns, and three rounds from the 3-pounders. All shots fell close to the target, although it was difficult to aim at a black spot against the sun’s glare. The enemy dived and went off, pursued by the decoy, who dropped a depth-charge over the disturbed water. Nothing further occurred. Within a short hour the ship had fought her first engagement and had suffered the keenest disappointment.

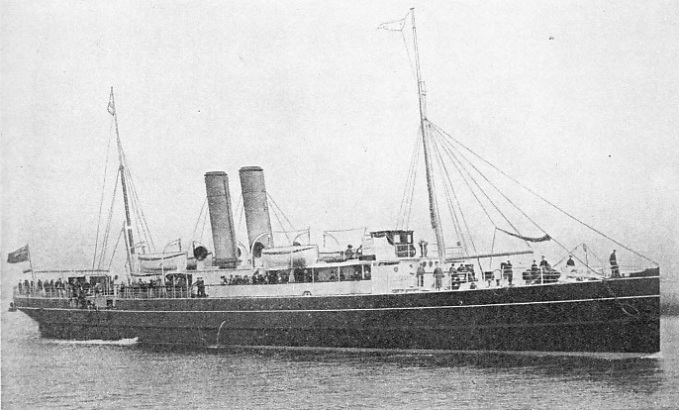

At noon the next day, in mid-Channel between Portland Bill and the Casquets, the Penshurst intercepted a radio from the Weymouth-Guernsey steamship Ibex that a submarine had been sighted at 11.44 a.m. twenty miles north-west of the Casquets. This news was most welcome, and the Penshurst now altered course. That also was the day when two British sailing vessels were sunk in much the same area; the Behrend (141 tons) thirty-five miles south-west of Portland Bill, and the Heinrich (98 tons) twenty-nine miles south by east of the Start.

The Q-ship did not have long to wait. At 1.50 p.m. the conning-tower of a submarine showed up five miles to the southward. After a few minutes the submarine turned east and dived. Overhead, coming from the Portland base, flew a seaplane. The seaplane saw the enemy and dropped a bomb, but without effect. What should Captain Grenfell do? It seemed improbable that the German would come back to the surface. The only chance of success was to drop a depth-charge. The maximum speed under water of such a submarine would be 6 knots, so that the Penshurst with her 8 knots might be able to get in a lucky explosion.

Aid from the Air

First, Grenfell spoke to the seaplane and explained what his ship was. The seaplane alighted alongside. It was arranged that the air pilot should guide the ship to the spot by dropping a signal-light, after which the depth-charge could be released. Unfortunately the seaplane had scarcely taken the air again when she crashed, broke a wing, knocked off her floats and began to sink.

The steamer lowered her gig and picked up the men, then she got alongside the wreckage, grappled it and was about to swing it inboard with her derrick when shells began falling round. On the port quarter some 6,000 yards away a submarine was on the surface.

Captain Grenfell stopped all salvage work, let the seaplane go, swung in his derrick, and made ready to fight. The gig was towed along the starboard side of the Penshurst, in the hope that the submarine would not see it, and the Q-ship jogged along again to the southwest. The German came up dead astern and course was altered to the eastward with the intention of keeping the submarine on the Penshurst’s port quarter, thus hiding the gig.

The submarine held on, firing occasionally and overhauling her prey, but still on the surface. When nearly in the position that the Ibex had indicated, the time and place were fit for final conflict. The Penshurst stopped her engines, the “panic party” rowed off in two boatloads to starboard, but the fighting men remained ready, hidden and expectant. Captain Grenfell watched his rival swerve out to port, motor round the steamer’s stern and approach the boats to get the ship’s papers from the captain.

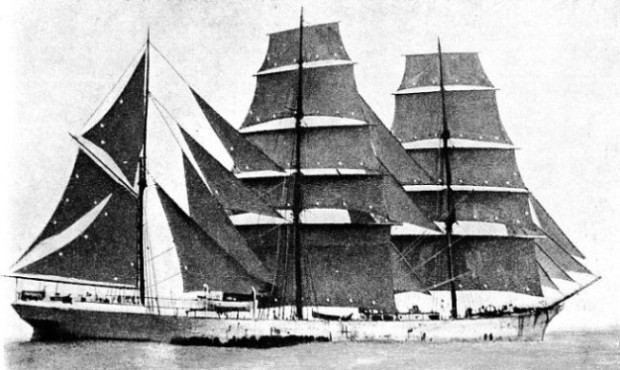

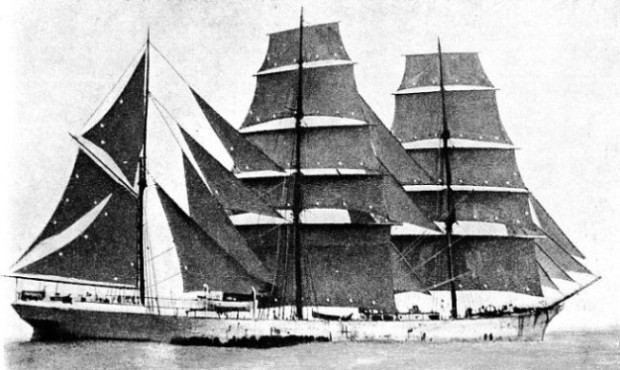

SUNK BY A SUBMARINE IN FEBRUARY 1917. The steel barque Invercauld (1,416 registered tons) was nearing the end of an Atlantic crossing when she was torpedoed and sunk by U 84 about 22 miles south-east of Mine Head, Co. Waterford, I.F.S. The crew of the barque escaped in the boats. Soon afterwards the Penshurst went in chase of the submarine, which fired a torpedo. The Penshurst, having avoided the torpedo, sent off the “panic party”, opened fire and hit the submarine’s conning-tower U 84 then made a crash dive. On her reappearance she saw the sloop Alyssum and retreated. Though damaged, the U-boat reached Germany safely.

There was a wait of less than a quarter of an hour. The submarine had reached the Penshurst’s starboard quarter, and was only about 250 yards distant. So satisfied and unsuspecting was the enemy that no one stood by her 8.8-centimetres gun forward of the conning-tower. Interest was directed on the boats.

With every gun bearing, the Penshurst opened fire and continued to fire at maximum speed. The second shot from the starboard 3-pounder penetrated the enemy’s hull into the engine-room and prevented her from diving. Over eighty shells were fired and almost all found their mark. The submarine’s hull was riddled and large portions of her conning-tower were blown away. After ten minutes she went down bows first. The Penshurst’s boats picked up Lieut.-Commander Erich Noodt, Lieut. Karl Bartel, Ingenieur-Aspirant Eigler and thirteen of the crew. Seven were killed by the shelling.

This submarine was UB 19, 118½ feet long, nearly 15 feet beam, carrying four torpedoes, one gun, one machine-gun and numerous bombs (for sinking captured ships). She belonged to the Flanders flotilla and had left Zeebrugge on November 22 to operate in the English Channel at a time when the U-boat campaign had become serious. That the Penshurst should have fought two engagements in two consecutive days after an eventless year, and that her fresh disguise should have completely fooled Noodt, must be remembered with interest. Captain Grenfell was awarded the D.S.O., one of his officers the D.S.C., and one of the crew the D.S.M. The sum of £1,000 was divided, and after the war a further sum came in the form of prize bounty from the Prize Court.

The Q-ship’s luck had changed suddenly from inactivity to achievement. A few weeks later she returned to the Casquets area, where another German submarine of the same type as UB 19 (though slightly newer and 2½ feet longer) was on duty. The enemy attached considerable importance to that section of the British trade routes. He could generally rely on meeting some cargo steamer bound up Channel from Ushant. The lost UB 19 was replaced by UB 37 (Lieut.-Commander Gunther). Steering on a north-easterly course from the Casquets, on January 14, 1917, the Penshurst sighted this Flanders boat.

In Action at Short Range

Five minutes passed, only 3,000 yards separated them, and Gunther opened fire, the shell falling short. After the usual “abandon ship” tactics the Penshurst waited, and the enemy closed until at 700 yards he stopped off the steamer’s starboard bow, broadside on. He then began firing, striking the Q-ship twice in succession. These two hits broke an awning ridge-pole, damaged the lower bridge, and severed the engine-room telegraph as well as the pipe to the hydraulic gear controlling the release of the depth-charge aft. Much more serious, however, was the human injury. The gunlayer and loading-number of the 6-pounder were killed while waiting hidden at their station, two men being wounded. They were the 6-pounder breech-worker and the signalman standing by ready to hoist the White Ensign, which was always run up immediately before engagement.

At first Captain Grenfell estimated that Gunther was going round to the boats on the port quarter, and there would be a chance of fighting the German at short range; but that estimate had to be revised and the action begun at once.

The White Ensign was run up at 4.24 p.m. The Penshurst with the first shot from her 12-pounder struck the base of UB 37’s conning-tower. Some German ammunition was struck, for a black cloud of smoke issued and then large portions of the conning-tower were noticed to be missing. The second shot brought further damage to the hull, and the starboard 3-pounder sent at least four more shells into the conning-tower. Thus riddled, UB 37 sank; but, to make certain, the Penshurst steamed over the spot and dropped depth-charges. Having cleared the neighbourhood of a dangerous ambush, Captain Grenfell picked up his boats and steamed northwards to Portland, where he arrived at 10 o’clock the same evening and sent his wounded into the Naval Hospital.

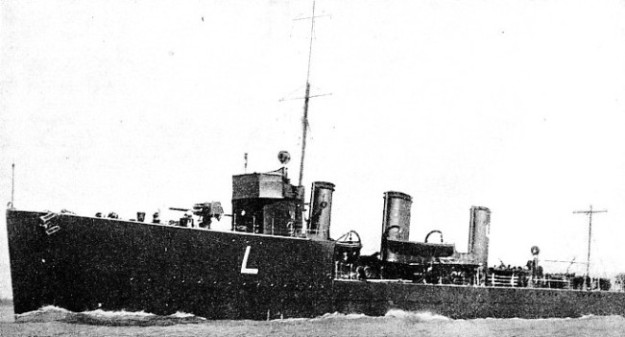

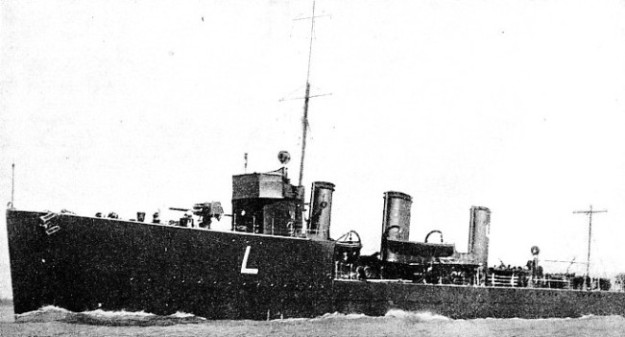

THE TIMELY ARRIVAL of H.M.S. Leonidas, a destroyer of the L class, saved the Penshurst during an engagement with an enemy submarine. On August 19, 1917, the Q-ship had been struck by a torpedo and was filling with water. She was in danger of sinking when the arrival of the Leonidas frightened off the submarine. Destroyers of the L class had a tonnage of 965-1,000 and a speed of 29 knots. Their length was 269 feet and their beam 27½ feet The armament included three 4-in. guns and four 21-in. torpedo tubes.

Only a few weeks after the UB 37 incident, the Penshurst was in the western approaches of the English Channel. On February 20, 1917, at 12.36 p.m., a submarine rose to the surface and began shelling. Half an hour later the Penshurst replied and hit the enemy's hull above the water-line. The U-boat managed to submerge without serious damage and, despite the depth charges which followed, got home safely.

Two days after meeting with this stranger, the Penshurst was off the south Irish coast steaming on a westerly course, some time before noon. Shortly before daylight that day the steel barque Invercauld (1,416 registered tons) was coming eastward from across the Atlantic and had only 120 more miles to travel before reaching port. She was about twenty-two miles south-east of Mine Head (Co. Waterford, I.F.S.), when right astern a submarine rose.

The wind was northerly and light. All sail had been set, but the Invercauld was not doing more than 2½ knots. The submarine had no difficulty in approaching and shelling. She fired a torpedo which blew 150 feet out of the Invercauld's side. The barque turned turtle, and the last her captain saw of her was the keel pointing to the sky. The boats got away before she capsized, but the cook (who had gone back to fetch some ham that was being fried) was blown through the galley door and over the ship's side, though he was picked up later, unhurt. The captain (who went below to save his chronometers) also had a narrow escape. In his boat was a man with a broken leg and a terrible gash in his head, as well as other injuries. “We had great difficulty,” relates the Invercauld’s captain, “in being able to pull at all with him laid across the thwarts.”

Famous Barque Destroyed

At 11.34 a.m. the Penshurst noticed that a submarine was steering west in the same direction as herself. Captain Grenfell made towards her at top speed but could not get near. And no wonder, since she was the modern U 84 (Lieut. Commander Rohr) with a surface speed of 16½ knots, twice that of her pursuer. Measuring 230 feet long, armed with one 4.1-inch gun, one 22-pounder and a dozen torpedoes, able to travel under surface at 9 knots, this submarine was a formidable foe. In twenty-one minutes she had disappeared.

Eight miles off could be seen H.M.S. Alyssum (one of the Queenstown “Flower” class sloops) escorting the large four-masted steamer Canadian. At 12.18 p.m. the Penshurst saw one of the boats from the Invercauld, and a few minutes later the barque’s upturned hull. Then a pair of periscopes was sighted rising from the sea 400 yards distant on the port beam, followed immediately by the track of a torpedo. It made straight for the Penshurst’s side, but by starboarding helm just in time the Penshurst dodged it by 15 feet.

Just after one o’clock the German was within 3,500 yards and began firing. The Penshurst’s panic party “abandoned” ship. At 1,500 yards the German submerged and made a thorough periscope inspection of the supposed coaster; but no one showed on board.

Rohr brought his vessel to the surface again and lay only 600 yards off the Penshurst’s port quarter. The only thing that remained was to order the steamer’s captain alongside with his papers and destroy the ship. An officer hailed the boat near him, but the British petty officer in charge of the boat knew what to do and (to gain time) pretended not to understand. The order was repeated. He answered that he was bringing the boat round by U 84’s stern: the secret intention was to give Captain Grenfell a clear range.

MORE THAN ONE ENEMY SUBMARINE WAS SUNK BY THE Q-SHIP PENSHURST. On January 14, 1917, she was attacked by UB 37. After the usual “abandon ship” tactics, the Penshurst awaited developments. The enemy closed to within 700 yards and began firing. Though hit, the Penshurst replied effectively. The first shell from her 12-pounder struck the base of UB 37’s conning tower. Other shells found their mark and the submarine sank. To make certain the Penshurst dropped depth-charges at the position where her enemy disappeared.

The boat’s crew had scarcely rowed more than three strokes when the Penshurst ran up the White Ensign and opened fire. The conning-tower was struck. Inside there was a flash, and explosive gases filled that compartment, injuring one man. Two more shells also hit, and the hull itself was holed. The German officer leapt down the hatch barely in time, and U 84 did a crash dive, but the forward hydroplanes jammed and she came up at a steep angle bows first. She was greeted with a further salvo of shells and dived again. Two depth-charges were dropped, and at 65 feet Rohr felt the fierce shocks. His craft trembled violently, most of the electric lights went out, and the climax was reached with the breakdown of such items as the gyro compass, the main rudder, and the trimming pump.

Had this been one of the Flanders eight-knotters, she would have been sunk. U 84 had to rise to the surface and all her crew came out on deck, while the Q ship’s gunners kept loading and firing. With his superior armament, Rohr now replied, but H.M.S. Alyssum arrived on the scene and her weight of fire decided the matter. The Germans took her for a fast destroyer — bows-on she did have that appearance — and sought safety in flight. As the greater-part of U 84’s damage was above the water-line she could still travel on the surface and the holes were plugged as well as possible. Away went the submarine, and for three hours she raced for her life. The Alyssum had been originally built for minesweeping, and her best speed was about 13 knots. Neither she nor the Penshurst could get near the enemy, and at 5.12 p.m. the fight ended with U 84 on the horizon.

By motoring always on the surface, keeping well out to sea during daylight, passing headlands by night, and generally avoiding our patrols, Rohr took U 84 back to Germany. There she received extensive repairs, and eventually Rohr took her back to the Irish area. Less than a year later — on January 26, 1918 — U 84 met her fate.

Torpedo and Gunnery Duel

After her indecisive struggle with U 84 the Penshurst had only a month to wait before taking part in another tussle. This time the scene was the eastern end of the English Channel, and again neither side was victorious. Q-ships were almost at the peak of their success; some had begun to show their limitations Their lack of speed and of armour meant inevitable weakness, whereas the big submarines with their 4.1-in. guns and 164 knots could attack from long range and approach only at the end for a final knock-out with torpedoes. Moreover, German commanding officers, warned by previous narrow escapes and taught by what they heard narrated, rarely allowed themselves to be surprised. Q-ship warfare had become fairly equally balanced.

This time not only did the Penshurst fail to sink the enemy, but she also was so seriously maimed that she had to be towed the following day into Portsmouth. The strain of the trying months had begun to tell, Captain Grenfell was invalided ashore, and by the time the ship had completed her refit a new commanding officer had been appointed. This was Lieut. Cedric Naylor, R.N.R.. who, as Captain Grenfell’s second-in-command, had taken part in the fights and knew the game.

On the afternoon of July 2, 1917, in the western approaches to the English Channel, an enemy just missed torpedoing the Penshurst by about 10 feet. Afterwards there was a gunnery duel for half an hour, and the Q-ship claimed to have hit her foe sixteen times. The arrival of three destroyers frightened the submarine away.

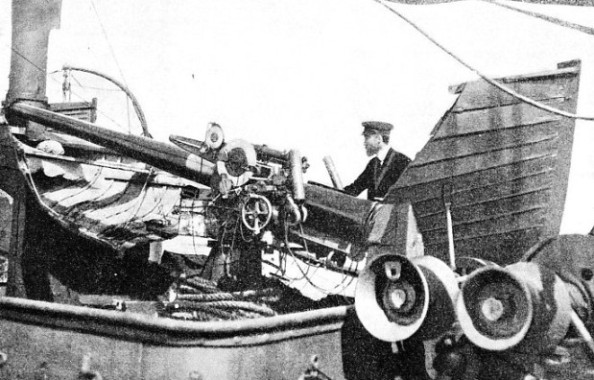

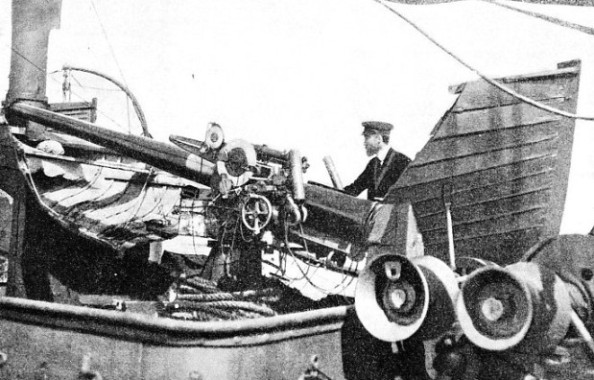

ONE OF THE PENSHURST’S 12-POUNDERS hidden in a dummy boat. Another 12-pounder was hidden on the starboard side ol the lower bridge. In addition, the Penshurst was armed with 6-pounders and 3-pounders. Effective concealment of armament, combined with the deception by the “panic party”, was a cardinal factor in the success of a trap-ship engagement. Other devices adopted for disguise in the Penshurst included the lowering of the aftermost of her three masts and the alteration of her colour-scheme.

A much more complicated and trying experience came the following August, also in the western approaches. In the the late afternoon of August 19 the Penshurst saw an enemy submarine six miles away crossing her bows, evidently getting into position for attack. The U-boat dived, and Lieut. Naylor calculated a torpedo would soon be fired. One was seen to break surface 1,000 yards from the ship, three points on the starboard bow.

The torpedo made a glancing blow just below the bridge. The explosion that followed sent a huge volume of water into the air, and flooded the upper and lower bridges as well as the after deck. With so much water on board the ship took a heavy list to starboard.

In addition. No. 2 hold had been penetrated, the starboard side of the lower bridge Was stripped, and the 12-pounder gun that had been concealed there was exposed to view. Moreover, the magazine had been flooded; and all controls from the bridge, and the Penshurst’s compasses, had been put out of action.

In spite of what had happened, within fourteen minutes of the explosion the steering gear had been connected up with the steering engine, the wireless repaired, a general signal for assistance sent out to H.M. ships and the Penshurst was steaming ahead prepared to fight.

At 6.5 p.m. the submarine again appeared. The range came down to 5,000 yards, and after a quarter of an hour the mystery ship opened fire with all guns from the port side. It seemed as if the enemy had been hit, for at the end of three minutes he dived. A period of suspense followed.

In the Penshurst the steering again went wrong. She got out of control and steamed round in circles. Shortly before 7 p.m. H.M.S. Leonidas (a destroyer) wirelessed to say she would reach the Penshurst at 7.30. It seemed unlikely that the Q-ship would still be afloat, and at 7.5 p.m. the submarine once more revealed herself on the surface, 7 miles astern.

The Last Encounter

At 7.26 the Leonidas came in sight, and the submarine dived and went into safer waters. Help had come, but it became advisable to place on board the destroyer every man who could be spared. The Penshurst trudged along in the direction of Plymouth, while the pumps just managed to keep her from sinking during the night and following forenoon. From the Scillies Naval Base a tug and two armed trawlers had been sent out, and at 1.30 p.m. the Penshurst was taken in tow. On August 21 the Penshurst arrived in Plymouth Sound.

The next time she went to sea, still commanded by Lieut. Naylor, she was armed with a 4-in. gun. On Christmas Eve, 1917, a U-boat was known to be operating in the Irish Sea. Hoping to intercept her, the Penshurst was steaming along, and about noon saw a submarine five miles ahead, steering at right angles for the usual “approach” tactics. The enemy disappeared, and shortly after came the track of a torpedo fired from only 300 yards, towards the port side of the steamer. Although the Penshurst put her helm hard a-port, she was struck between boilers and engine-room. The explosion made a great hole, the ship stopped dead and began to settle down aft. The sides of the dummy boat and the after gunhouse collapsed with the explosion. Lieut. Naylor decided to send away his panic party in the one remaining boat and on rafts. After having circled below surface round the ship, the submarine rose and started shelling at 250 yards range. The Penshurst being so low in the water could make her guns bear only as the ship rolled and pitched. Six rounds were fired, of which one scored a hit abaft the conning-tower.

The arrival of a P-boat frightened the enemy away. The Penshurst, however, could not be saved, and she sank that night at eight o’clock after the crew had been taken off. She was lost in the Irish Sea where her former rival, U 84, was to perish a month later.

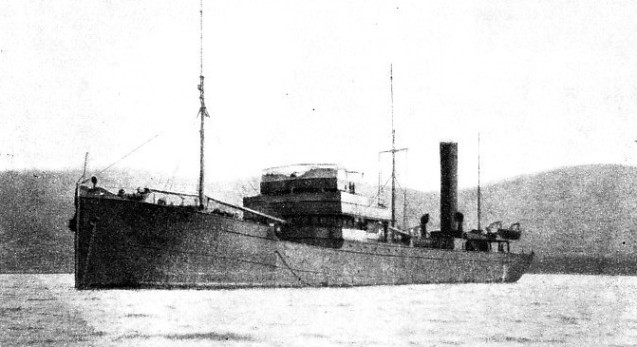

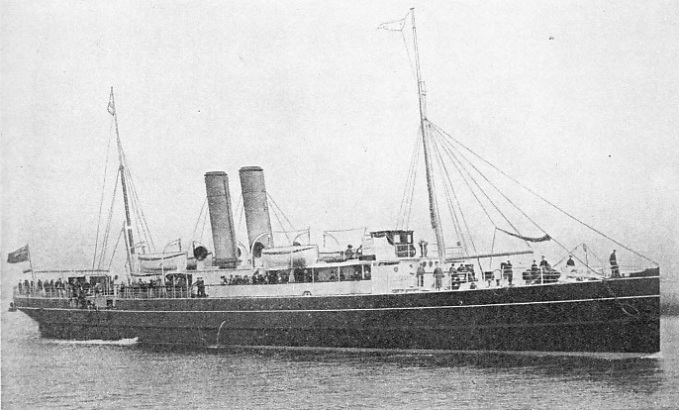

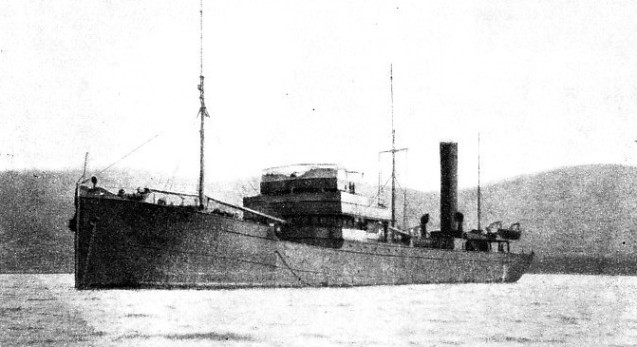

A RAILWAY STEAMER INVOLVED. On November 30, 1916, the Ibex, a cross-Channel steamer of the Great Western Railway, plying between Weymouth and the Channel Islands, reported by wireless that a submarine had been seen at 11.44 a.m. twenty miles north-west of the Casquets. This submarine proved to be UB 19, sunk the same day by the mystery ship Penshurst. The Ibex, built at Birkenhead in 1891, had a gross tonnage of 1,150 Her length was 265 feet, her beam 32 ft. 8 in and her depth 14 ft. 2 in.

You can read more on “The Convoy System”, “The Fortunes of War” and “Trap-Ships of the Fishing Fleet” on this website.