© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Heroism and Disaster at Sea: HMS “Victoria” and HMS “Birkenhead”

The extraordinary sinking of HMS “Victoria” in 1893 in the Mediterranean and the loss of the troopship “Birkenhead” off Danger Point, near Simon’s Bay, South Africa, on February 26, 1852, will long be remembered for the heroism that these catastrophes called forth

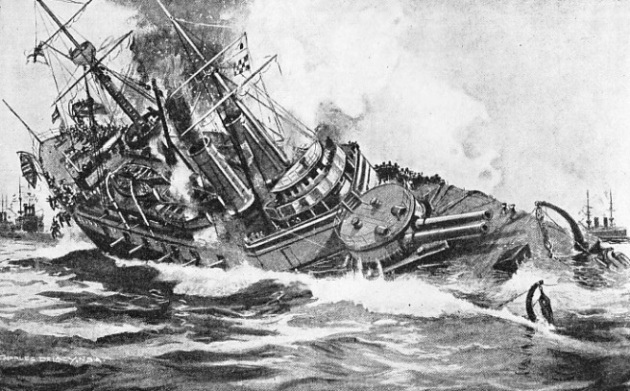

LAST MOMENTS OF THE SINKING BATTLESHIP. An impression of H.M.S. Victoria a short time before she went down by the head causing great loss of life. The forward turret of the Victoria carried two guns, each of which weighed 110 tons. The Benbow, the Sans Pareil and the Victoria were the only ships of the Royal Navy to be fitted with this type of gun.

ON Thursday, June 22, 1893, the British Mediterranean Fleet left Beyrout, on the coast of Syria, at 10 a.m. for Tripoli, about sixty miles away. This Fleet was under the command of Vice-

It was a perfect Mediterranean day. sunny and calm. The Admiral did not intend to anchor again until the evening, so that there was plenty of time, to carry out a few manoeuvres. For some time after they had left the anchorage, the ships steamed in one long line abreast of one another, at a speed of about 8 knots. These thirteen sea giants made a fine sight on the azure blue of the

summer sea.

At 2 p.m. the Admiral ordered a manoeuvre which brought the ships into two divisions, steaming in line ahead. In one division were the Nile, Dreadnought, Inflexible, Collingwood and Phaeton, led by the Victoria, and in the other division were the Edinburgh, Sans Pareil, Edgar and Amphion, headed by the Camperdown, which was the flagship of Rear-

This was an order which caused a great deal of surprise, for it was customary when ships steamed in two lines for the distance between to be sufficient for the ships to turn round towards one another without any fear of collision. As the ships of the Mediterranean Fleet required at least three cables, or 600 yards, to turn in normal conditions, it was obvious that if they were only six cables apart they could not turn inwards without a collision. On board the Victoria, the staff decided that possibly the Admiral had made an error when he had said “six cables”. So before the signal was made, the Admiral was asked again and reminded that the ships could not turn without more space apart than six cables. The Admiral was quite determined as to what he meant — namely, that the divisions were to be six cables apart. He wrote the instructions on a piece of paper which he gave to the Flag-

The signal was therefore made and all the Captains in the Fleet were surprised at the order. Although unusual, however, it did not involve any immediate danger,as perhaps the Admiral intended to do some manoeuvre other than turning the ships towards one another. The Fleet therefore steamed on in the same order.

At 3.15 the Admiral, who had been down below, went up to the bridge and surveyed his Fleet. At 3.25 he directed two more signals to be made. One ordered the Victoria to swing round to port sixteen points — a left-

Every one wondered if the Admiral had made a mistake. As soon as Admiral Markham saw the signal he questioned it, but when another signal was made asking him what he was waiting for, he decided in his own mind that probably Admiral Tryon was going to wheel his division round him and make a long about-

The captains of all the other ships, including the Camperdown, were satisfied that all would be well, and these ships hoisted a signal indicating “Your signal is seen and understood”. When this was reported to Admiral Tryon he ordered his signals to be hauled down, which meant “Obey my orders instantly”.

Even at this juncture there was a little apprehension. What had he in his mind? Was he going to wheel right round outside Admiral Markham’s Division? Did he expect Admiral Markham to wheel round him? Was this why he had laid such emphasis on the six cables, to make it obvious that the ships could not turn towards one another in safety? To preserve the order of the Fleet did he

mean that the Camperdown was to finish up with the Victoria still on her starboard beam? If this was intended the Camperdown would have to make a big wheel outside the Victoria’s division.

As the signals fluttered down, they were obeyed without hesitation. All concerned had complete and unreserved confidence in their Commander-

So in broad daylight in a flat calm, the Victoria and Camperdown, each flying an Admiral’s flag, slowly but surely turned towards each other.

Disastrous Manoeuvre

It was obvious to anyone who watched them that a collision was inevitable. The Admiral remained unmoved, but Captain Bourke of the Victoria ordered one engine to be put full speed astern to turn the ship in a smaller circle. Captain Johnstone of the Camperdown did the same thing. “Full speed astern both engines”, was the next order given in either ship, followed quickly after by “Close watertight doors” and “Collision stations”, but it was too late.

With a tremendous crash the Camperdown, still moving ahead, rammed the Victoria on the starboard bow. Splinters of steel flew in all directions as she pushed the Victoria over several degrees. For some minutes the two ships were locked together until the Camperdown, less badly damaged, backed astern with her engines. The captains of the other ships saw the disaster and handled their ships with great skill, thereby avoiding any further collisions. The Nile and Edinburgh were close behind the Victoria and Camperdown.

The Victoria was badly holed, and immediately began to settle by the bow with a list to starboard. The other ships at once began to lower their boats, but Admiral Tryon, standing calmly on the top of the bridge, ordered a signal to be hoisted not to send them. It is possible that he hoped to get the Victoria beached in shallow water in safety.

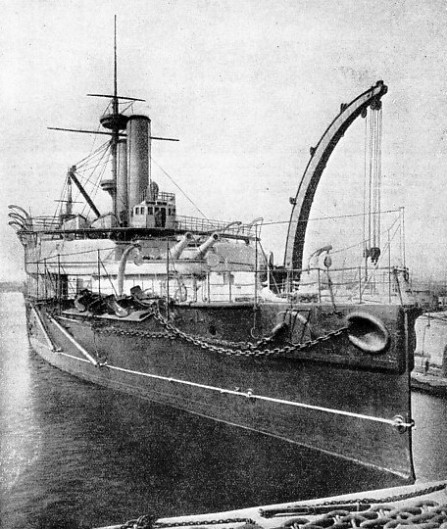

THE FIRST BATTLESHIP of the “Admiral” class, H.M.S. Collingwood was begun in 1880. On June 22, 1893, she was in the same division of the Mediterranean Fleet as the ill-

Meanwhile, the officers and men of the Victoria went about their duties as quietly and efficiently as had those of the Birkenhead forty years before. Captain Bourke was ordered to go below to see that all the doors were closed and to ascertain the extent of the damage done. While doing this, he was able to observe that there was “no panic, no shouting, no rushing aimlessly about”, and remarked on the discipline and self-

Some were closing watertight doors and scuttles, others were trying in vain to place a collision mat over the hole. Others, again, were getting the boats ready for lowering, and in the bowels of the ship the engineer officers, engineers and stokers were going about their business as usual. The doctor was attending to his patients, keeping them calm and arranging to have them brought on deck. Among these was the Commander of the ship, later to become Admiral of the Fleet Earl Jellicoe. Although in bed with fever, Commander Jellicoe made his way on deck and went to his post as the others did.

As in the sinking of the Birkenhead, the men not required for special duties were ordered to “fall in”, facing inboard. They remained fallen in four deep, as the ship settled more and more.

Admiral Tryon stayed on the bridge and ordered the ship to be headed for land, but the helm would not work although the engines moved ahead. He soon realized that his ship was doomed for he remarked to the Staff Commander, “I think she is going”, and gave instructions for another signal to be made, “Have the boats ready, but do not send them”.

Sunk in Thirteen Minutes

Captain Bourke completed his rounds and was on his way back to the bridge to report — but he never got so far. The men working on the forecastle remained there calmly with water up to their waists till the order was given for “all hands on deck” and “fall in”.

The effect of their arrival, dripping wet, must have made the men already fallen in realize to the full the danger their ship was in —but not a man moved. Finally an order was given to “turn about and face the sea”, which was obeyed with a stoicism beyond all praise, for not a man fell out.

Suddenly the ship gave a tremendous lurch to starboard. Men fell, and crashes of crockery and furniture resounded through the decks. High above the noise of falling debris could be heard the voice of the chaplain, the Reverend Samuel Morris — “Steady, men, steady”.

To the horror of those who witnessed the accident, all at once the ship quickly turned right over and then plunged head foremost to the bottom of the sea only thirteen minutes after she had been rammed.

As the ship turned over the order was given to “jump”, and all the men who could jumped overboard or through the ports. Others were sucked down with the ship; those below were drowned as if they were rats in a trap. The last seen of the Victoria was her screws revolving madly in the air, showing that the engineers and stokers had remained gallantly and boldly at their place of duty to the end.

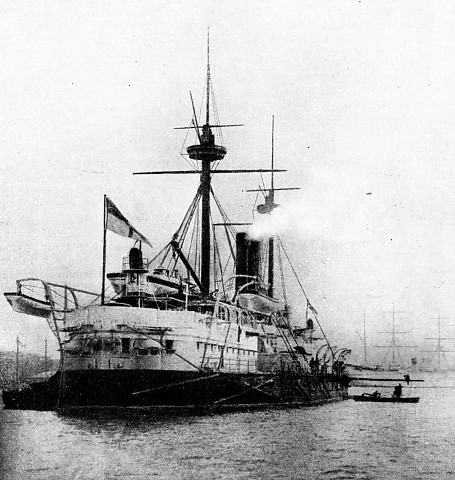

IN THE SAME DIVISION AS H.M.S. CAMPERDOWN, the battleship which rammed the Victoria, H.M.S. Edinburgh avoided a similar fate by skilful manoeuvring. The Edinburgh was a steel battleship of 9,480 tons displacement. With her sister ship, H.M.S. Colossus, she had a speed of 14½ knots. The two ships were the first to be given compound armour.

Boats from all the other ships now rushed to the assistance of those in the water, but before the scene could be reached many had been taken under by the confused water which covered the surface where the Victoria had disappeared. Others had been hit by wreckage and stunned, or caught by the propellers and killed instantly. Some were able to cling until rescued, to objects floating about, but others unable to swim had little chance of survival. As Captain Bourke said, it is scarcely to be imagined that there was a single survivor who could give a clearer reason for his being saved than that he was more fortunate than his neighbours. In all, twenty-

In this manner a noble man went to his death showing his greatness to the end. His last words were to Midshipman Lanyon, who was standing bravely by his side: “Do not stay there, youngster, go to a boat”. Neither of them was ever seen again.

Meanwhile, the Camperdown was in a bad way, but she was damaged less than the Victoria and not in such a vulnerable place. The command of the Mediterranean Fleet had now fallen on Admiral Markham, who was able to carry on in his own flagship, thanks to the skill of her men, who patched her up and saved her, although it looked at one time as if the tale of disaster was not yet completed.

The whole world rang with the news of this terrible collision. Great Britain’s finest battleship had been lost and the bravery and courage of her crew set a world-

A court-

When great disasters occur at sea two things are generally the outcome-

In the long roll of disasters there are two which are outstanding — the sinking of the Victoria and the loss of the Birkenhead —because they are examples of mass discipline and will be told and retold as long as men take a pride in their race. Curiosity as to the cause of the disaster is outweighed by admiration for those men of the Army and Navy who were not to blame.

In 1852 one of many wars in South Africa was in full swing. Reinforcements and drafts of troops were continually needed to keep the military strength up to establishment. Among the many ships employed to carry troops was the 1,400-

She sailed from Cork Harbour on January 7, 1852, with 680 souls on board. The military personnel of officers and men comprised drafts from ten different regiments, the 2nd Queen’s Foot, the 6th Regiment, the 12th Royal Lancers, the 12th Regiment, the 43rd Light Infantry, the 45th Regiment, the 60th Rifles, the 73rd Regiment, the 74th Regiment and the 91st Regiment. All were under the command ot Lieut.-

The Birkenhead reached Simon’s Bay, near Capetown, the naval base of the Cape, on February 23. There, fortunately, some of the women and children were landed, leaving twenty on board. Having received his sailing orders from Commodore Wyrill, the Senior Naval Officer, Captain Salmond left Simonstown on February 25 for Port Elizabeth, on the south coast, to land drafts. The total number on board was now 648.

It was a fine evening when the Birkenhead steamed down Table Bay and a course was set which it was calculated would keep her well clear of the land. A calm, still night followed, but a heavy swell was coming in from the South Atlantic which gave the ship a gentle roll. There was no reason to anticipate any danger, for although it was dark, the night was clear and lights ashore could easily be distinguished. Soon after 10 p.m., Captain Salmond and all those not required for duty turned in.

A Hidden Reef

At midnight, the beginning of the middle watch, Mr. Davis, the Second Master, took charge of the bridge and saw that the look-

The ship was proceeding at a speed of about 8 knots when shortly before 2 a.m. the man in the chains sounding shouted out, “By the deep twelve”, indicating that the water had suddenly shoaled and there was a depth of only twelve fathoms. He hastily started to take another sounding, but before anything could be done, the Birkenhead had crashed on to a reef of rocks off Danger Point. The whole ship quivered from stem to stern so violently that there was no need to give an alarm, for all on board knew that something had happened. They were quickly on deck in any odd clothes they could scramble into over their night attire.

The ship was proceeding at a speed of about 8 knots when shortly before 2 a.m. the man in the chains sounding shouted out, “By the deep twelve”, indicating that the water had suddenly shoaled and there was a depth of only twelve fathoms. He hastily started to take another sounding, but before anything could be done, the Birkenhead had crashed on to a reef of rocks off Danger Point. The whole ship quivered from stem to stern so violently that there was no need to give an alarm, for all on board knew that something had happened. They were quickly on deck in any odd clothes they could scramble into over their night attire.

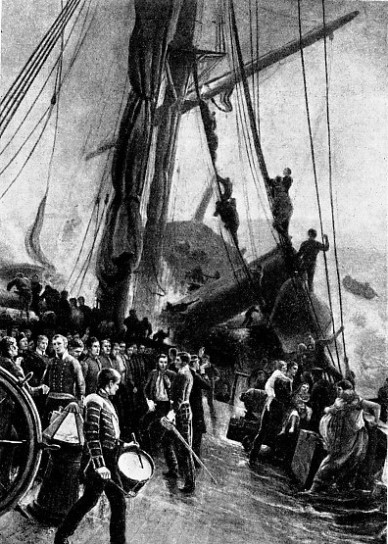

THE WRECK OF THE BIRKENHEAD is portrayed by Thomas M. Hemy in this striking illustration. The Birkenhead was an iron paddle-

Captain Salmond rushed on to the bridge and at once ordered an anchor to be let go and the engines to be stopped. Soundings taken indicated that although the water was only twelve feet under the bows, there were sixty feet under the stern. Salmond ordered the engines to be put astern. This turned out to be unfortunate, because the ship was held fast by a pinnacle rock which protruded through the bottom. The effect of the order was to cause the ship to rip a hole in her bottom.

Water rushed in, extinguishing the fires and putting the engines out of action. The lower decks were soon flooded. Meanwhile, Colonel Seton had arrived on deck. He called his officers together and impressed on them the necessity for discipline and silence. Then he ordered the troops to fall in. This they did as if on the parade ground, although the ship had begun to list. Captain Wright of the 91st was detailed by the Colonel to attend on Captain Salmond and to see that all his orders were carried out. They were issued quickly. “Sixty men man the pumps”. “Sixty help to hoist out the boats on the paddle-

Officers and men obeyed these orders calmly and without confusion as if it were all part of a day’s work. There was little hope of help from anywhere, as this was before the days of wireless. The best chance of attracting attention was to fire guns; but when the gunner tried to reach the magazine, he found that part of the ship flooded. He had to be content with burning blue lights and firing rockets in a vain hope that they might be seen. These spluttering, meteoric flashes merely helped to make the scene on deck more ghastly and terrifying than before — ghastly, but grand, for troops could be seen heroically standing on the poop.

Captain Salmond had already given orders to lower the boats because it was evident that the ship could never be saved, and safety lay in this direction if the boats could be released quickly enough. But the odds were against them in every way. The ship was pounding heavily and rolling with the swell and some of the boats were so wedged by the bulging of the deck that they could not be moved. In some instances the gear for lowering the boats was found to be in bad condition.

“Women and Children First!”

In the darkness the men struggled with ropes, but the tackles of one boat broke and those working on it fell overboard and were drowned. The clearing away of the boats took such a long time that there was no time to clear them all. Only two cutters and a gig got away in time, which left only three boats for more than 600 persons.

In the stillness of the night, to the ears of all, almost all doomed to die, came the order from the bridge: “Women and children first — place them in the cutter”. Colonel Seton passed the order on and an ensign and sergeant superintended its execution. It was a difficult task because the women, dishevelled, scantily clad and carrying their sleepy children, were loth to leave their husbands. A cutter under the charge of one of the Master’s assistants was alongside and Colonel Seton stood at the top of the gangway with sword drawn to ensure a safe passage for the women — but his sword was not necessary.

As soon as they were safely stowed in the cutter, Colonel Seton ordered the boat to be cast off and to lie clear of the ship. The other cutter, which had about thirty men in her, was ordered to do likewise, but the gig did not get away until later. Meanwhile, on deck, orders were given that the horses should be blindfolded and put overboard, thus giving them a chance to swim ashore.

Scarcely were the boats clear of the side when the surging of the ship caused her to break in two near the foremast. The funnel fell crashing down on top of the men releasing the boats on the paddle-

The men manning the pumps remained at their post to the bitter end, in the vain hope that they were doing some good, but all were drowned, faithful unto death.

When Captain Salmond realized that the ship was doomed, he gave orders for all those who could swim to jump overboard. This order was heard by Colonel Seton and his officers, but their first thought was that the boats were already crowded with women and children and they might be swamped. An appeal was made to the soldiers, but they did not need it.

The last definite order received from their own officer was “Fall in”. It was never cancelled. The officers quietly shook hands with one another, some vainly hoping to meet again ashore. Others were unable to swim and could only hope to survive by clinging to flotsam.

A few minutes later the Birkenhead broke in halves, and as the poop went slowly down the bravest of the brave went down with it and disappeared just twenty-

They had little hope. Although land was not far away dense kelp seaweed made approach to it difficult and perilous. Some found wreckage and driftwood to cling to, but most were doomed to an awful death, for the sea was infested with man-

The Captain and Colonel Seton went down with their men, setting the example of bravery and courage. They had saved the women and children — they could do no more.

Faultless Discipline

Nothing now remained of the Birkenhead except one mast showing above the surface of the water. To the mast some fifty men were clinging in the hope of survival. Only the fittest were left next day, as many exhausted with the cold and the shock slipped into the water; others thought floating wreckage offered a better chance of safety and went for it. It was a sheer trial of endurance and pluck, and forty were eventually rescued the following afternoon by the schooner Lioness.

This vessel, coasting near the land, had previously met with the two cutters, sighting one at 10 o’clock; the other attracted her attention later. Hot drinks, warm clothing and rest Were given by the skipper to the weary-

The sea was searched without any result, but searchers on the coast soon came across sixty-

Luckily Captain Wright had been in South Africa before. He knew the district and cheered his comrades with the assurance that there was a village a few miles distant, so that they were able to endure until assistance came. A final count was then taken; 648 had sailed from Simonstown — 193 were saved — not a woman or child was lost.

As the senior surviving officer, Captain Wright made an official report to the Military Commandant which sums up all that need be said of the discipline maintained. “The order and regularity that prevailed on board, from the time the ship struck till she totally disappeared, far exceeded anything that I thought could be effected by the best discipline; and is the more to be wondered at, seeing that most of the soldiers had been but a short time in the service (and came from different regiments). Everyone did as he was directed; and there was not a murmur or cry among them until the vessel made her final plunge.”

Queen Victoria expressed her “high admiration of the discipline, fortitude and devotion displayed by all the officers and troops on this occasion” and her people agreed wholeheartedly.

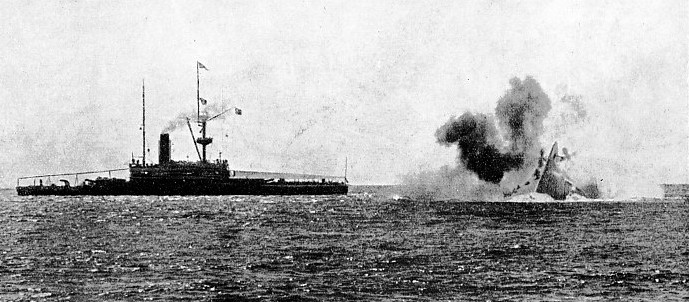

THE FINAL PLUNGE. An amazing photograph of H.M.S. Victoria as she disappeared beneath the water on June 22, 1393, with her propellers still revolving. The Victoria had been completed only three years before. She had a displacement of 10,470 tons, a length of 340 feet and a beam of 70 feet. Her speed was nearly 17 knots, and in addition to her two 110-

You can read more on “The Drama of Life-

“Medals for Acts of Bravery” on this website.