© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Captain Fryatt and the “Brussels”

One of the most tragic and yet heroic episodes of the war of 1914-

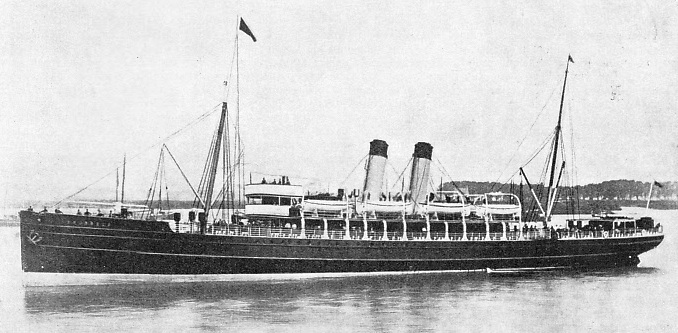

A SYMBOL OF HOPE. The Brussels, by maintaining her services between Harwich (Essex) and the Continent at the beginning of the war of 1914-

WHEN Gourlay and Company launched the twin-

The war of 1914-

To the Germans she signified frustration. So long as she sailed, she and her sister ships heartened the neutrals and induced them to continue their traffic with Great Britain. To stop that traffic the Germans were prepared to go to any lengths, for they realized that the outcome of the war would in the last resort depend upon the courage of the men of the Mercantile Marine of the Allied and neutral states. It was to destroy the moral of the seamen as well as the ships which traded with Great Britain that the Germans instituted their relentless submarine campaign.

Some crews of neutral ships, impressed by the havoc wrought by the submarines, refused to sail. That was what the Germans desired. But the Dutch at Rotterdam and at the Hook of Holland saw the Great Eastern steamers maintaining their service, in spite of the submarines.

It was a most anxious time for the masters. Although the vessels were unarmed passenger steamers subject to the usual international sea law of search and capture, they were now menaced by the torpedoes of the submarines which could and would sink without warning — a risk to which the shipping of the world had never before been subjected.

Early in February 1915 there came into the hands of Captain Charles Fryatt, of the Brussels, a secret paper from the Admiralty concerning the steps to be taken if he should meet with a submarine. It was marked Confidential, and was worded as follows:

“In no circumstances is this Paper to be allowed to fall into the Hands of the Enemy.

“This paper is for the Master’s personal information. It is not to be copied, and when not actually in use is to be kept in safety in a place where it can be destroyed at a moment’s notice. All previous orders on this subject are hereby cancelled.

“Such notices as call for immediate action may be communicated verbally to the officer concerned. 10th February, 1915.”

There is no need to quote the whole of the orders here, except the notes headed A: “No British merchant vessel should ever tamely surrender to a submarine, but should do her utmost to escape. . . If a submarine comes up suddenly close ahead of you with obvious hostile intention, steer straight for her at your utmost speed, altering course as necessary to keep her ahead. She will probably then dive, in which case you will have ensured your safety, as she will be compelled to come up astern of you.”

So Captain Fryatt learned how he might counter the attack of a submarine by steering straight at her and forcing her to dive. These were the orders of the British Admiralty as to how he should act if he met with a submarine.

On March 28, 1915, the Brussels pulled out from Parkeston Quay with Captain Fryatt on the bridge, bound for Rotterdam. Steaming at full speed on the course laid down by the Admiralty, she was nearing the Maas Lightship, off the coast of Holland, when Captain Fryatt saw some four or five miles away a big submarine approaching on his starboard bow.

It was the U 33, under Commander Gansser, who was just starting out from Zeebrugge to carry out a raid on shipping.

What might have happened if Captain Fryatt had obeyed the signal of the U 33 to stop is open to conjecture. Captain Fryatt, however, paid no attention to the signal. The instructions of the Admiralty were clear in his mind, and he at once acted upon them to escape. Having signalled down to the engine-

His change of course was followed by a change of course on the part of the submarine, and Captain Fryatt realized that she was manoeuvring into a position to torpedo the Brussels, as was afterwards admitted. Both vessels were now converging at full speed, with the distance between them rapidly decreasing. As soon as Captain Fryatt saw what was about to happen he

swung the bow of the Brussels dead at the submarine.

A Marked Man

At once the submarine dived, exactly as the Admiralty instructions had suggested, and for the next ten or fifteen minutes Captain Fryatt and his Chief Officer, Mr. Hartnell, watched tensely for her.

The U 33, travelling blindly under water, pushed up her periscope to gain a sight of her quarry when the Brussels was only two or three yards away. Captain Fryatt saw the periscope emerge by the port bow and slide away as the steamer travelled ahead at top speed. The Brussels had covered four or five miles before the U 33 came up again, by which time the steamer was out of danger.

Captain Fryatt reported the matter, as he was in duty bound to do, and the entry in his log is so quiet and restrained that it is worth placing on permanent record in these pages:

“1.10 p.m. Sighted submarine two points on starboard bow. I altered my course to go under his stern. He then turned round and crossed my bow from starboard to port. When he saw me starboard my helm he started to submerge and I steered straight for him. At 1.30 his periscope came up under my bows, port side, about 6 feet from the side and passed astern. Although a good look out was kept, I saw nothing else of him. I was steering an E. by S. course at the time of sighting him, and brought my ship to a north-

Gansser also reported how the Brussels had forced him under. From that moment the captain of the Brussels was a marked man.

There was no doubt that the German authorities at Zeebrugge were determined to bring him and the Brussels to account for having escaped from the U 33 so boldly. Four times in the next three months the Brussels was attacked by a submarine, and under the skilful direction of other masters she managed to escape.

BETWEEN FOUR LIFTING VESSELS, the Brussels, raised 22 feet from her position in the mud off the head of Zeebrugge Mole, was taken to Heyst, on the neighbouring coast. Commander G J. Wheeler, who was responsible for the raising of the Brussels, was in charge of the enormous task of clearing Zeebrugge Harbour of the obstructions that had been deliberately placed by the Germans on evacuation. The Brussels was towed to Heyst on August 4, 1919, the fifth anniversary of the declaration of war by Great Britain.

Meanwhile Captain Fryatt carried on his accustomed duties, while the Germans carefully collected every scrap of evidence they could find concerning him. An account of his exploit was given in the House of Commons, and was added to his file against such time as the enemy could use it. The sole concern of Captain Fryatt was to bring his ship and passengers safely to port, and the increasing intensity of the submarine campaign made him the more intent on safeguarding the lives committed to his care. On June 22, 1916, the Brussels lay at the quay at Rotterdam embarking passengers and mails.

Entrusted to the care of Captain Fryatt was a sealed diplomatic mail bag containing confidential documents from the British Consul General at Rotterdam. Captain Fryatt had orders to call at the Hook of Holland to pick up another batch of mails.

The mails at the Hook were duly shipped and about 11 o’clock at night the Brussels was moving out of the harbour, bound for the Thames, when Captain Fryatt and his first officer saw a rocket sail up in the sky from the shore.

They passed the Maas Lightship and had dropped it a dozen miles astern when they detected a small vessel in the darkness. Captain Fryatt could not make out what it was, but as the Brussels passed he saw a flash-

He and his first officer, Mr. Hartnell, kept sweeping the seas with their night glasses as the Brussels sped along at her best speed. Somewhere in the darkness Captain Fryatt knew that there was another steamer showing no lights and following the same course as his own. Not knowing where the other steamer was and failing to pick her up in the darkness made it rather trying to those on the bridge of the Brussels.

At last, about 12.30, Captain Fryatt ordered the port and starboard lights to be switched on for a minute or two, to warn the other steamer, wherever she was, of his own whereabouts and thus avoid any risk of a collision.

Confidential Papers Destroyed

But there were other vessels abroad that night looking for the Brussels, and a quarter of an hour later the blow fell. All round the steamer the forms of German destroyers suddenly appeared. There was no escaping them. Captain Fryatt saw that they surrounded him completely, so when they threatened to fire if he did not stop there was nothing for him to do, if he wished to preserve the lives of his passengers, but to obey.

Having moved quickly to his cabin, he gathered his confidential papers and the diplomatic mail bag, then he went to the engine-

The German officers, full of excitement, rang the telegraph of the Brussels for full speed ahead. There was no response. They had forgotten that the engine-

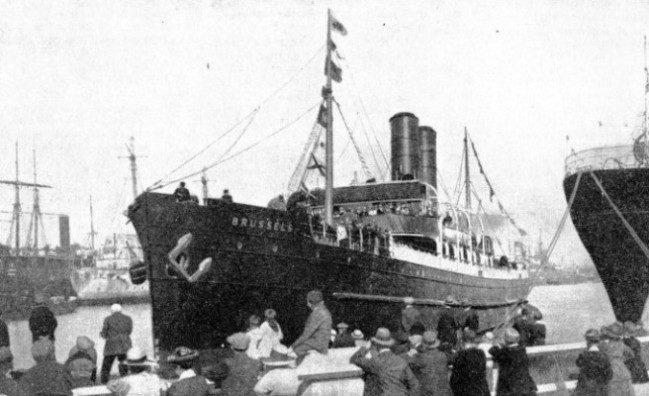

Without delay the Germans sent some of their own men below, and after one or two unexpected movements which taught them how to control her, they brought her by daylight to the occupied Belgian coast, where they hoisted the German colours over her. That morning of June 23 she came to Zeebrugge, where she remained for nearly six hours before proceeding along the canal to Bruges, the banks of the canal being lined with soldiers as she passed.

RISING TO THE SURFACE after having lain in 58 feet of mud. Sixteen 9-

On June 28 Captain Fryatt and Mr. Hartnell were taken to Ruhleben Internment Camp, from which they were removed under escort on June 30. By July 2 they were imprisoned at Bruges. What followed was an attempt to intimidate the master mariners of England and prevent them from sailing. As with all other similar forms of intimidation, it failed.

For three weeks Captain Fryatt was confined alone in a cell, pressed hard with questions by which the Germans sought to incriminate him as well as to induce him to incriminate Mr. Hartnell and other masters of the Great Eastern ships.

Meanwhile the Foreign Office asked the American Ambassador in Berlin, Mr. Gerard, to engage a counsel for him. Mr. Gerard wrote to the German authorities on July 20 and, getting no reply, wrote again, marking his note “very urgent”, on July 22. Not until July 26 was he informed that Captain Fryatt was to be tried on the following day.

Without having received any advice or assistance, Captain Fryatt stood before his accusers on July 27. The only charge that could be brought against him was that he was “strongly suspected of having attempted to cause injury to the forces of Germany”.

Major Naumann, a German officer, did his best to defend him. Had Captain Fryatt mentioned that he was acting under Admiralty instructions in heading for the submarine with a view to escaping, the court would not have condemned him, for the German code gave protection to an enemy in these circumstances. On this point alone a counsel appointed by the American Ambassador would have saved him. But no mention of the confidential orders passed Captain Fryatt’s lips. Not once did he refer to them.

“I have done no wrong”, said Captain Fryatt to his accusers.

Mr. Hartnell said afterwards: “When he rose to his feet to speak for himself there was not a German present who could face him”.

By 4 o’clock, after having considered for a minute or two, the court condemned him. For a little while he was allowed to walk in the prison yard, but he had not long to wait for the climax.

Harbour in Chaos

Two hours after the verdict had been given his captors took him from his cell and led him to the prison yard, where they tied him to a convenient post and shot him.

As Sir Archibald Hurd says in his official history, The Merchant Navy: “Captain Fryatt’s innocence is alike attested by British history, by British laws and by British privileges at sea. He upheld a right which is vital to those who go down to the sea, and defended it with constancy, loyalty and unflinching courage”.

The Brussels, which had escaped the submarines so often, was used by the Germans as a submarine depot ship at Zeebrugge. It was generally thought in British naval circles that she was torpedoed and sunk by a British coastal motor boat just off the head of the Mole, but it appears that the coastal motor boat had torpedoed a dredger and not the Brussels.

With the end of the war came the vital question of clearing the Belgian ports. Commander G. J. Wheeler a clever Admiralty salvage officer who had salved dozens of ships during the war and had just cleared up the wrecks in Spain and Portugal, was instructed by the Admiralty to take charge of the clearing of the harbour of Zeebrugge, so that the navigable channel and Mole could be used as soon as possible. Clearing the entrance to the Bruges Canal was of secondary importance, and Commander Wheeler was told to work there only when bad weather made work impossible elsewhere.

He found the port in chaos. The Germans had sunk all the ships they could. They had obstructed the place with overturned dredgers, submarine pontoons and seaplanes. They had sent a lightship to the bottom, upset cranes and trucks from the Mole, and generally done their best to prevent the harbour from being used for a long time to come. Off the head of the Mole the enemy had sunk the Brussels to serve as a breakwater and boom defence, filling in intervening spaces with an odd trawler or two.

It fell to Commander Wheeler to remove alp this wreckage in the shortest possible time. He pressed into his service some 400 Belgians and as many salvage craft and officers as he could obtain, and set about his task. His was the brain that planned and directed the whole of the operations. He was wrestling with the dredgers, the trawlers, the lightship and the Brussels, as well as with the other conglomeration of wreckage, all at the same time. If operations were stopped on one wreck because of something unforeseen, Commander Wheeler transferred the men to work on another to save time. When the weather prevented work on the lightship or the wrecks at the end of the Mole, he brought the squads in to work on the wreckage alongside the Mole.

THE SALVED SHIP’S DECK as it appeared when she was raised from Zeebrugge Harbour. The Brussels was overgrown with barnacles and weeds. She had been under water for about a year.

Having put Lieutenant R. Brooks, R.N.V.R., in charge of the work to be carried out on the Brussels, Commander Wheeler sent down divers to learn as much as possible about the state of the ship. They found she had settled about 18 feet into the mud and was full of ooze. She was fully submerged at low water, which ruled out any possibility of pumping her out to raise her, but fortunately she was on an even keel.

The fact that he had no plans of the Brussels was rather a handicap to Commander Wheeler. She was 18 feet in the mud, which almost filled her. The erroneous report that she had been torpedoed led him to think she was badly damaged somewhere below, so he saw that the only way of dealing with the steamer was to lift her bodily. He was able to gain a good idea of her length, beam and depth. So far as he could calculate from the data at his disposal, he would have to lift a weight of nearly 4,000 tons, allowing for 1,000 tons of mud in the hull. He rather over-

He considered all his factors. The tide at Zeebrugge rises 18 feet, which gave him sufficient lift to bring the steamer to the top of the hole in the mud. Four of the lifting craft would enable him to lift 5,000 tons, which gave him an ample margin. By filling their tanks when he pinned them down and pumping out the tanks as the tide rose, he could gain another 4 feet of lift, which would enable him to carry the wreck over the lip of the hole.

A trawler had broken the foremast of the Brussels, so the shattered mast was burned off and lifted ashore. Cutting away the top hamper of a ship is always impressive, but Commander Wheeler was not concerned with doing anything spectacular. His sole aim was to do as little damage as was necessary and lift her out of the way as soon as possible so as to clear the harbour.

On June 7, 1919, he wrote in his diary: “Result of survey on Brussels shows that vessel was not torpedoed, but internally mined”. She had two holes on the starboard side about 5 feet in diameter, one being down near the bilge keel. There was another hole about 5 feet long and 6 feet wide near the bilge keel on the port side of the sunken vessel. The brass ports of the steamer had all been removed — that was an indication of the Germans’ need of brass metal in those days — and Commander Wheeler set the carpenters to work making covers for the port-

The demand for salvage craft and gear elsewhere made it no easy matter to collect the lifting vessels and wires for the Brussels. Eventually, however, the salvage officer’s urgent demands brought one or two more lifting craft out from England. He was thus able to assemble the necessary four lifting craft and the sixteen 9-

Unexpected Delays

Every day brought its troubles. Often the weather was too bad to allow work to be done on the steamer. Wires and chains chafed or broke on the other jobs. The lightship was found to have a fractured keel and had to be blasted to pieces and lifted out of the way. The overturned dredger, with its chain of buckets, was an endless source of trouble.

Then, to make matters worse, there was trouble with some of the riggers of the Reindeer, one of the lifting vessels. The Belgian authorities were pressing the salvage officer to clear the Mole so

that it could be opened at the earliest moment, and the riggers were asked to work overtime on Thursday, June 12. They refused. Next day was Friday the 13th, and Commander Wheeler’s diary explains how he dealt with men who would not work in an emergency: “Sacked riggers of the Reindeer”, he wrote.

By June 14 his work was sufficiently advanced for the Mole to be opened officially and for a train to be run along it. He thus anticipated by one day the official opening of Ostend.

A day or two later President Wilson proposed to pay an official visit with the King of the Belgians to see the damage done by the enemy during the evacuation and to inspect the operations in progress. By then, Commander Wheeler was busy pumping out the dredger which had proved so difficult. To his surprise there came an order to stop pumping. He promptly obeyed, for he had enough troubles on his hands without seeking more.

THE SHATTERED FOREMAST of the Brussels. As she lay in the harbour of Zeebrugge, where she had been sunk on the evacuation of the harbour by the Germans, a trawler had broken her foremast. Before the Brussels was raised, the mast was burned off and lifted ashore.

On June 18 the King of the Belgians and President Wilson, under the guidance of the Naval and Military authorities, paid their visit to Zeebrugge, and the officer who had ordered the pumps to be stopped now ordered them to be started up, thinking to stage the spectacular and impressive feat of lifting the dredger before the eyes of the distinguished visitors. The unspeakable dredger refused to move. The officer who had given the order to stop pumping had done so without consulting the salvage officer on the spot, and had overlooked one vital factor. Directly he had stopped the pumps, the dredger had filled up with mud again. She continued to sit stubbornly on the bottom all the time the visitors were at Zeebrugge.

It was July 3 before the salvage ship Linton swept the first 9-

The bridge of the Brussels, which the heroic Captain Fryatt knew so well, obstructed the work, so they picked it up with their derricks and lifted it out of the way. More bad weather gave the Brussels a few days’ respite, but on July 16 Commander Wheeler got five wires under her, and by July 26 the sixteen wires were in place.

Three of the lifting craft that had been used in the interval on the other wrecks were now prepared to lift the Brussels. By the time work was finished on Saturday, August 2, the four lifting vessels were in position with the sixteen 9-

On Monday, August 4, the lifting vessels, their tanks full of water, were pinned down tightly to the wreck. The pumps, having emptied the tanks of the lifting craft, lightened them sufficiently to give them that extra 4 feet of lift which, added to the 18-

Doomed by the Slump

To Commander Wheeler’s consternation, when he came to tow her she would not move. The lifting vessels were all pulling at full power, but they made no impression.

One of the young salvage officers, in the excitement of the moment, had forgotten to slip the anchor wire on the starboard lifting vessel aft, as he was instructed to do. That was the reason why the Brussels did not shift. The oversight was quickly remedied, and the collection of salvage craft moved in a compact body slowly over the sea for two miles until the wreck touched bottom off Heyst in 37 feet of water.

Next day the salvage officers pinned the lifting craft down again and carried the Brussels inshore until she lay in 30 feet of water at high tide. By August 6 the task was as good as completed, for when the tide ebbed there were only 7 or 8 feet of water where she lay. After that it was merely a question of patching and pumping to refloat her. She was a sorry mess, all overgrown with barnacles and weed, as different from a spick-

For the moment it rather looked as though her useful life was finished. Instead of being broken up, however, she was converted at Leith into a cattle boat, and the passenger steamer whose name once resounded round the world served her country in a humbler guise, carrying cattle between Ireland and England.

Bad times loomed up. A change took place in her owners. The British and Irish Steam Packet Company, to which she had been transferred, changed her name to Lady Brussels.

For a year or two longer she went on her uncomplaining way, with cattle lowing between decks and the smell of the byre about her. But age and her wounds and her sojourn on the sea-

RETURNED TO SERVICE, after having been successfully salved, the Brussels acted as a cattle boat, sailing between Preston, Lancashire, and Dublin, I.F.S. Her first sailing from Preston, above, aroused considerable popular interest. Her owners changed her name to Lady Brussels, and she served on the cattle service until 1929, when she was broken up at Port Glasgow.

You can read more on “The British Admiralty”, “Dramas of Salvage” and “Raising the German Fleet” on this website.