© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Fifty Years in Sail (1)

Vivid extracts from the log of the late Captain James William Holmes, who served in famous vessels in the heyday of the sailing ship era. His experiences before he achieved command are related here and illustrated from some of his own paintings

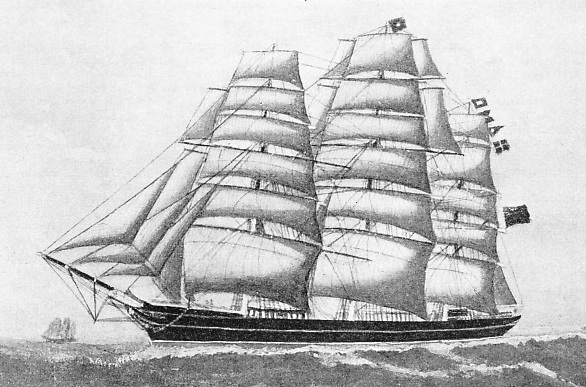

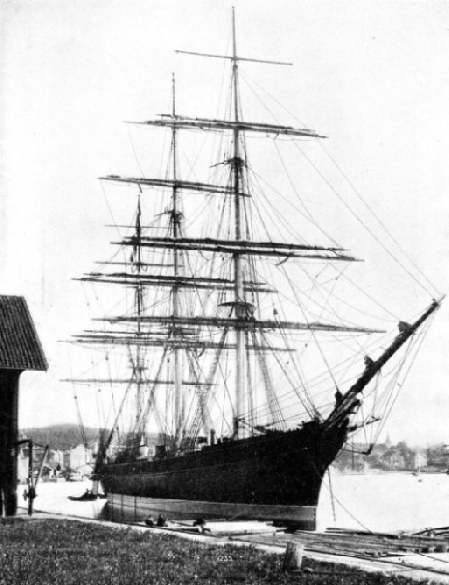

A SOARING MAINMAST 150 FEET HIGH was one of the distinctive features of the Salamis. Captain Holmes, who sailed in her as third mate and painted the original of this illustration, thought “she was the most beautiful thing afloat”. She was an iron ship of 1,130 tons gross, built at Aberdeen in 1875.

THE last half-

Whereas before the war of 1914-

Then, in the height of their pride and perfection, they pass completely. The moment of their departure was unnoticed, but their glory was undimmed. They continued to make fine passages,

they fought for every inch through the fury of the gale when the world had ceased to mark their exploits and bets were no longer taken on the date of their arrival.

With the object of preserving the memory of those glorious ships of yesterday, I have painted all those in which I sailed between 1869 and 1921. And for the life on board them, let memory recall the days that were.

I cannot say I chose the sea as a career; that was done for me before I was born. All my ancestors were sailors from Deal and Dover. My father, grandfather and great-

She was a regular West Indian trader, loading sugar at St. Kitts (Leeward Islands) at Christmas and reaching London the following March — and the five months of that round voyage were a nightmare of starvation. The tea I poured into my numbed little body that first night at sea made me heave my inside up. I think it was concocted from coir and broom bristles, but it never owned a tea-

The salt beef had to be chopped through like a block of mahogany, and the salt pork — streaked with green — could be smelt all over the ship when the first cask was broached.

Well do I remember the morning we arrived in London. The overlooker was awaiting us. As he came aboard he said “Had any breakfast?” knowing I had had none for about 150 days, and adding, “Go ashore and get some”, as he gave me half a crown. And all that half-

As this trip was intended as a trial before my apprenticeship, it is perhaps unnecessary to remark that I did not repeat it, but was apprenticed next December in the Blair Athol, which, if not better, was perhaps “not quite so bad”.

The Blair Athol was a wooden barque of 443 tons register, built at Shoreham, Sussex, and was the biggest vessel belonging to that then busy little port; for Shoreham could boast 350 brigs and barques built for the Mediterranean and other trades. The Blair Athol — a Mediterranean and Black Sea trader — was a nice-

We made our first trip to Alexandria (Egypt), and on the way through the Mediterranean we passed a ship in the night. Hailing her, we asked her name, and through the twilight came a name famous a generation before. “The Marco Polo!” thinly floated back, as the gallant old veteran, then a Norwegian, passed like a ghost of her former days.

A Brutal Skipper

In Alexandria I saw another ship renowned in bygone days. This was Captain Marryat’s ship, the Ariadne, in which he wrote his novels. She was then used as a coal hulk for the P. and 0. Company, a pathetic but common fate for ships that were not “sold foreign”.

I painted a picture of her for her skipper, and it is almost unbelievable that a man who has seen the Marco Polo and Ariadne afloat should live to see the Queen Mary built, and remember all the famous ships between them. The next trip we made from South Shields to Alexandria, the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov reaching the latter in the depth of winter. And here we suffered all that a Russian winter and a brutal skipper could inflict upon us.

We lay seventeen miles off the port of Berdianski, inside a fourteen-

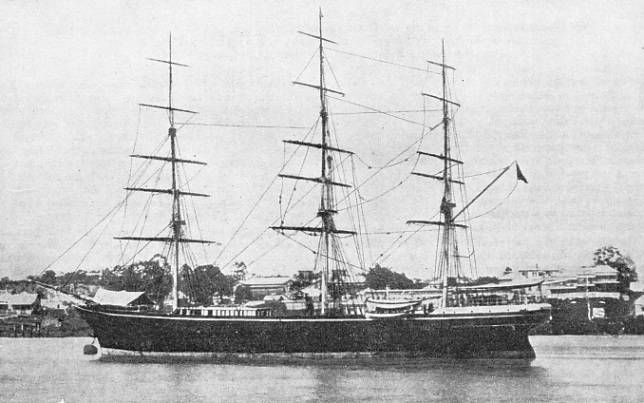

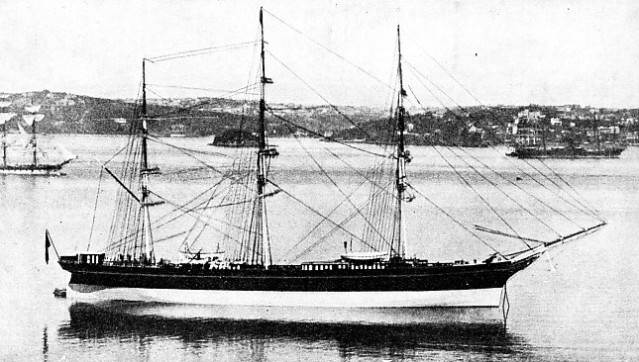

BUILT IN 1870 by Maudslay and Field for J. Willis and Son the Blackadder (970 tons gross) was the sister ship of the Hallowe'en, which came home from Shanghai in ninety-

So the days passed with ever-

There was, however, a 14-

The Blair Athol’s end came before our time was out, and we boys were transferred to the Argosy to finish our apprenticeship. And here befell an incident which might have finished it indeed. We took coals from Shields to Montevideo (Uruguay), and sailed from there in ballast to Valparaiso (Chile) and Iquique for saltpetre.

We were twenty-

There remained but one hope between us and destruction, and that was muscle. So we put out our boat, with four men rowing, to pull the ship from the jaws of death — a frail tug surely to be pitted against the relentless force of the open Pacific swell. We four apprentices, left to man the ship, took spells of rowing two hours on and two hours off with the four A.B.s, while the skipper and his wife took turns at the wheel.

So we toiled and strained through the long hours of that day and night, towing a ship with four men’s arms against the might of the ocean swell, which, lifting the ship’s boom with every roll, carried the boat back and broke several oars.

Then on Monday morning a puff of wind blew from the shore and so we “came into the haven where we would be.”

Rusty Mud as Drinking Water

But on our homeward voyage from Iquique we narrowly missed the worst of sea tragedies — no water. Before leaving Valparaiso we filled up from the water-

We were straightway put on rations of three half-

At the end of this voyage I passed for second mate at the age of 19 and returned to Deal for Christmas with my certificate in my pocket. And there it was destined to remain for many weary months. I could not have struck a less favourable opportunity for putting it into action. All the January wool ships were coming in. Nothing was sailing. Paid-

Moreover, such was the fashion of those times, that the very beauty of my clean-

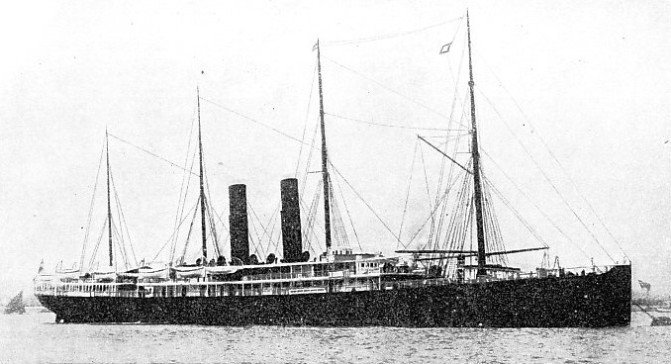

STEAMSHIP WHICH SANK IN A LANDLOCKED HARBOUR. When Captain Holmes was in the Hallowe'en at Sydney, Australia, he saw the Orient liner Austral, reputed to be unsinkable, go down in 49 feet of water. The curious disaster was due to negligence during coaling operations The Austral was later salved and returned to service. Built in 1831, she was of 5,524 tons gross. Her length was 456 feet, her beam 48 ft. 2 in. and her depth 33 ft. 10 in.

So after many cold and fruitless days of weary dock tramping, and cutting allusions to my chin, I joined the Kosciusko as A.B. The wooden ship Kosciusko was built in 1863 for the Aberdeen White Star Line. She was 1,192 tons register, built of pitch pine, and painted green with a yellow stripe, and with towering white masts like all Thompson’s ships. Her figurehead was Kosciusko himself, the Polish patriot.

She was a passenger ship with a poop 70 feet long taking up half her deck length, and we had four or five passengers aboard. Perhaps it was in deference to their presence that we burned sidelights all the voyage, but the Kosciusko was the first ship I was in which showed her lights in mid-

The Kosciusko carried twenty-

Compliment to Plimsoll

Samuel Plimsoll, pleading his Bill for a loading line in Parliamentary debate, instanced George Thompson’s as the one line that never loaded their ships deeply, and in return for this compliment they called their next ship the Samuel Plimsoll. They thought of calling the Salamis the Sarah Plimsoll, but she was built as sister ship to the Thermopylae, so she was named accordingly.

Thompson’s ships sailed two a month all the year round, one for Sydney and one for Melbourne, always leaving London on a Saturday and anchoring at Gravesend till Monday to allow the crews to sober up. The same thoughtful practice was followed by Wigram’s and Green’s Blackwallers.

A VIVID PAINTING of the Blackadder by Captain Holmes. The Blackadder had a gross tonnage of 970 and was built in London in 1870. She had a length of 216 ft. 7 in., a beam of 35 ft. 2 in. and a depth of 20 ft. 6 in. These measurements were also those of her sister, the Hallowe’en built at the same time, except that the Hallowe’en had a gross tonnage of 971.

We made a splendid run to Sydney, which at that time could boast of little but its harbour, and that was just as Nature left it, for it was a day’s work to moor a ship at a stage. Two anchors were dropped off the shore side, and two trees, 80 or 90 feet long, were lashed to the rails, and a platform built on them. But every inch was crowded with ships loading wool, and great was the race between them for the January wool sales.

We arrived on New Year’s Day, 1876, and the skipper, on paying off the ship’s company, offered me the third mate’s job, but I was not anxious to sail again in the same ship. Fine ship though she was, there were then more ships than parish churches.

In February 1876 I sailed as third mate of the Salamis, and a lovelier ship it would tax the imagination to conceive. She was built by Hood’s of Aberdeen for George Thompson in 1875, and was a companion in iron to the Thermopylae in composite. She was the first iron ship I was in, though Thompson’s Patriarch, built in 1869, was the first iron ship from Aberdeen yards. The Salamis had a billet or fiddle figurehead, with a little Grecian warrior on each side, and the yellow stripe round her green hull was not painted, but gilded. She was glorious to behold. I think she was the most beautiful thing afloat.

We were seventy-

We were thirty-

W e lay a month in Shanghai waiting for something to load. Still nothing could be found for one of the fastest and handsomest of a gallant fleet. The lovely queen was indeed a beggar maiden seeking anything available, and finding nothing; so at last we loaded ballast and ran down to Hong Kong, making an extraordinary passage of two days through the Formosa Channel in the north-

e lay a month in Shanghai waiting for something to load. Still nothing could be found for one of the fastest and handsomest of a gallant fleet. The lovely queen was indeed a beggar maiden seeking anything available, and finding nothing; so at last we loaded ballast and ran down to Hong Kong, making an extraordinary passage of two days through the Formosa Channel in the north-

CONSORT TO THE FAMOUS THERMOPYLAE, the Salamis was built by Hood’s of Aberdeen for Thompson’s Aberdeen White Star Line in 1875. An iron vessel of 1,130 tons gross, she had a length of 221 ft. 7 in., a beam of 36 feet and a depth of 21 ft. 8 in. She had a billet or fiddle figurehead with a Grecian warrior on either side. Her hull was painted green Captain Holmes sailed as third mate of the Salamis in February 1876.

No steamboat could do it then, and perhaps not even now in similar circumstances. Fast she undoubtedly was. Although the smallest iron ship of the fleet, her average from Melbourne to London was eighty-

The Kinfauns Castle, a beautiful ship, previously commanded by my uncle, Captain W. Holmes, who took her from the stocks in 1868 for the tea trade, was the most talked-

An Extraordinary Disaster

The Loch Fergus was built at Glasgow in the early 1870s by D. And W. Henderson with all the lavishness that the builders’ art could bestow on her, all her deck woodwork being varnished teak, and her cabin panelled in mahogany and bird’s-

The Hallowe’en was the first of Willis’s ships in which I sailed as mate and, like the Blackadder in which I sailed later, she was built in London by Maudslay and Field in 1870. She was intended for a tea clipper, and justified her short existence in that trade by coming home from Shanghai in ninety-

When I sailed in her we were bound for Sydney, where she had already established her fame in the wool trade, having made her maiden trip there under Captain J. Watts in sixty-

While lying in Sydney Harbour on her next trip, I saw the most curious disaster I have ever witnessed. Looking from my porthole one night I saw the fine new steamer Austral (reputed “unsinkable”) go down in forty feet of water in a landlocked harbour. Calling the second mate and all hands, I lowered our boats and picked up some hundred survivors.

Next day we learned the cause of this disaster. She was coaling through large square ports apparently without proper supervision, till the ports reached the water-

On her next outward voyage the Hallowe’en might have been my first command had Fate but delayed my letter of resignation for a few hours. For the very night I wrote it was the captain’s celebration, and, failing to receive Willis at his usual hour, 9 a.m., he was fired on arrival. “The ship would have been yours,” said Old John to me, “but you are no longer in my employ”.

That was the second time I had missed command by a few hours, the first being at the age of twenty-

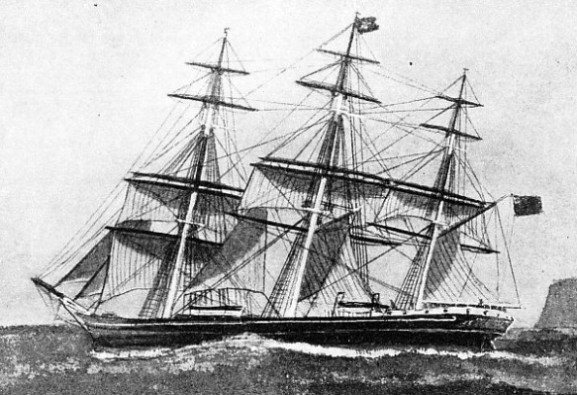

AN ABERDEEN WHITE STAR CLIPPER in the same fleet as the Salamis and the Thermopylae. The Miltiades was built at Aberdeen in 1871 for George Thompson and Company, owners of the famous fleet of clippers. With a gross tonnage of 1,495, she had a length of 240 ft. 6 in., a beam of 39 ft. 3 in. and a depth of 23 ft. 3 in

You can read more on , “Fifty Years in Sail 2”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and

“Thermopylae and the Cutty Sark” on this website.