© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Wild Boat of the Atlantic: the “Dreadnought”

The career of the clipper “Dreadnought” is a stirring chronicle of romance and recklessness on the Atlantic

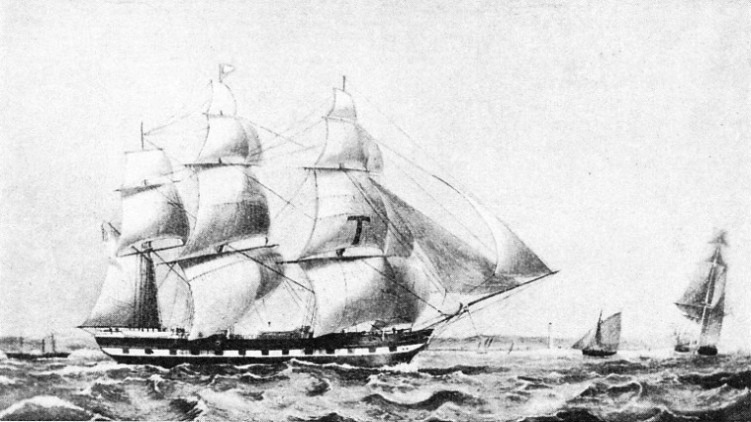

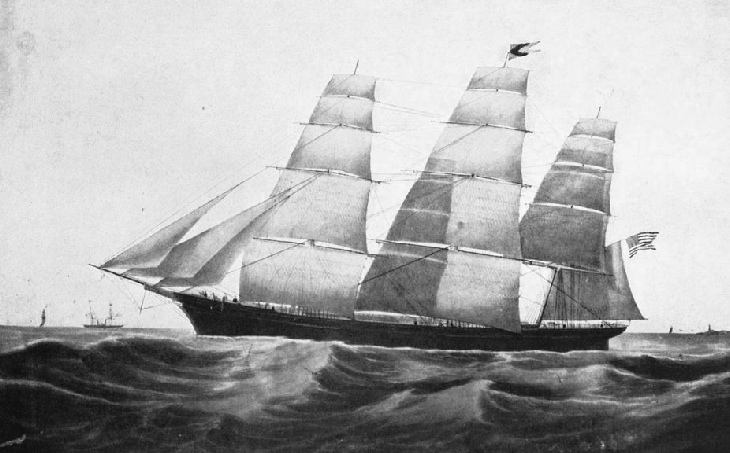

RACING HOME ACROSS THE ATLANTIC. A fine study of the Dreadnought, one of the fastest of all sailing ships. This vessel was built for the American Red Cross Line in 1853 to compete with the steamships of that period. She was 200 feet long on her keel, 212 feet on her deck, had a beam of 41½ feet and a hold depth of 26½ feet. Primarily an emigrant carrier, the Dreadnought could take 200 passengers in her ‘tween decks; she had, in addition, accommodation for a number of saloon passengers.

THE clipper packet Dreadnought of 1853 may be regarded as the high-

When she was built, steamers had been running regularly across the Atlantic for fifteen years, during which time sailing packets had been steadily losing ground. Until 1850 they had, at least, retained the profitable trade of carrying emigrants, but after that date, when the Inman Line of steamers was started, sailing ships had lost even that monopoly and their position was desperate. Throughout the ’forties stories of the horrors of the emigrant trade in sailing ships appeared in the press. When William Inman, a young man of twenty-

Even before Inman’s venture there had been considerable improvements, and the poorer class of sailing ship was gradually being forced off the trade. Emigrants were able to discriminate, and speed alone was no longer the sole inducement. Transatlantic passages were given much publicity in the press, and the ship with the best reputation secured the business. The more reputable packet owners improved their tonnage and aimed at a better average speed without undue discomfort to their emigrant passengers.

Donald McKay was the outstanding figure among New England shipbuilders catering for this policy. In 1843 the packet St. George, the second ship that he designed and built, was the first passenger packet owned by the American syndicate which ran its ships as the Red Cross, or St. George’s Cross Line. The heads of this syndicate were David Ogden, E. D. Morgan, F. B. Cutting and others, all practical shipping men with an eye for a fine ship. The St. George was of 845 tons register, but by 1846 the standard tonnage for this trade was over the 1,000 mark.

When the Inman Line began there was a sharp division of opinion among the clipper shipowners and builders as to whether this new menace should be met by the most extreme type of fine-

The shrewd directors of the Red Cross Line saw the danger and realized that they needed a remarkable vessel to check the inroads of the steamer into their business. Speed was a necessity, but the new type of ship must also have the maximum comfort possible in a sailing clipper, especially if she hoped to attract passengers of the cabin class. The Red Cross Line chose excellent builders in Currier and Townsend, many of whose designs had proved fast; in addition the owners aimed at getting the views of the practical seamen from among whom they intended to select the ship’s master.

The directors persuaded Captain Samuel Samuels, a young man who had already made a high reputation as a captain of emigrant packets, to join their venture. They offered good terms, including a present of shares in the ship, commission on all that she earned and good pay; in return he had to take partial responsibility for her design and was to be wholly responsible for the supervision of her construction.

They could not have chosen a better man, although he had not yet had the opportunity of showing all those qualities which were to make him successful. Practically self-

That was a rough school, better for seamanship than for manners, and young Samuels made the most of it. Crimps and West Indian pirates were incidents in his boyhood. At the age of twenty-

The “Packet Rats”

Samuels took a passage home in the sailing packet Catherine. He made so great an impression on her master that he was offered the post of mate for a voyage while waiting to take up the promised command of the Angelique, then homeward bound. He commanded the Angelique for three years on the emigrant trade between Amsterdam and New York, although she was by no means a crack vessel, Samuels made the most of her and gained a high reputation.

On the strength of this he was selected by the Red Cross syndicate for the command of what was intended to be one of the finest, although not the largest, of the clipper packets. The respect paid to the master of such a ship in shipbuilding and shipping circles in New England was both a revelation and a lesson to him.

In his own words: “Swearing, which appeared to me so essential in the make-

She was a fine ship, however, universally admired by the critical seamen who sailed the Atlantic in the ‘fifties: 200 feet long on her keel, 212 feet on her deck, she had a beam of 41 ft 6-

The Dreadnought, which was primarily an emigrant carrier, as were all the sailing packets, could accommodate over 200 in her ‘tween decks, which were available for cargo on the eastward run. She had also accommodation for a number of saloon passengers who preferred the sailing ship to the steamer, in a big saloon or cuddy aft with cabins leading out of it. Her captain’s manner and reputation soon proved a great advertisement, and the fact that he carried his wife and family on board was a guarantee of the respectability of the ship’s conduct, by no means then universal among packets. This made a special appeal to saloon passengers, and the ship was fully booked a season in advance.

THE REPUTATION OF A FAMOUS SHIPBUILDER, Donald McKay, was made in the middle of the nineteenth century by the number of fast clippers built by him. Above is the Joshua Bates, one of Enoch Train’s transatlantic packets, designed by McKay. The large “T” in the fore topsail, more conspicuous than the normal house flag, will be noticed. This clipper marks the transition stage between the former square-

Her lines would not permit her to ghost along in the faintest of airs as did the extreme clippers, but faint airs were not the normal condition on the Atlantic, and she had the reputation of never having been passed by a sailing ship in more than a four-

In eleven years she made thirty-

During the year 1859, the most eventful in the ship’s history, occurred her much-

“Dear Mr. Morrison, -

“Yours,

“S. S.”

Official sources confirm the fact that the Dreadnought had a series of westerly gales to help her all the way to Queenstown, and her build let her take full advantage of this. Samuels himself attributed much of his success to the good discipline of his crew and to his belief in forcing the ship at night as well as by day. Within a few years of the time when it was almost universal to snug down at night-

“Night is the best time to try the nerves and make quick passages. The best shipmasters that I have sailed with were those who were most on deck after dark, and relied upon nobody but themselves to carry canvas. The expert sailor knows exactly how long his sails and spars will stand the strain; the lubber does not, and therefore is apt to lose both.”

Unfortunately the owners did not keep their copies of the official log, and the captain’s own were destroyed in the accident which ended his Western Ocean career; but there is little reason to doubt the passage, considering its long acceptance by expert critics.

The other incident in 1859 was the suppression of a mutiny which might have become one of the most disgraceful in the history of the sea. The clipper packets were manned principally by a special type of seamen known as “packet rats”, for the most part

Liverpool Irishmen, who were magnificent seamen but among the wildest afloat. Any sign of weakness displayed by the afterguard led to trouble, and the methods of the bucko mates, brutal as they seem nowadays, were necessary. Many surviving sailing ships were almost controlled by these hands, and the sight of the Dreadnought running regularly with perfect discipline on board, and a reputation which put many others to shame, was distasteful to them.

A plot was hatched out in a boardinghouse for sailors, one of the worst in Liverpool. A gang, the “Bloody Forty”, was responsible for it. A few of this gang in the forecastle of the Columbia had recently murdered Captain Bryer for offending their dignity, and it was decided to treat Samuels in the same way. Liverpool detectives and the Board of Trade learned of the affair anti advised Samuels to refuse to sign on a crew composed almost entirely of the gang; his professional pride was touched, and he boasted that he would master them before he reached New York. He took the precaution, however, of drawing their teeth as far as possible before they left Liverpool, while the officials were still on board. He made every man have the point of his sheath knife broken off in the carpenter’s shop. Then, laying all hands aft, he addressed them, saying that he knew of the oath that they had taken in the Liverpool boarding-

The storm soon broke. The helmsman was insolent and attempted to knife the captain, who promptly knocked him senseless and had him put in irons, the second mate taking the wheel. The crew refused duty until the man was released and assumed a threatening attitude, while a number of emigrants on board huddled as close to the poop as they were allowed. Samuels armed himself with two revolvers and, with his faithful dog Wallace, a huge creature, went forward and drove the mutineers into the forecastle, although he had good reason to know that all their knives had been repointed.

Some of the passengers wanted the ship put into Queenstown; others, including a number of former German soldiers, volunteered to help the captain. The first mate was an old man, the second a coward, and the third fully occupied with the wheel, so that Samuels wanted more support than his loyal apprentices could give him. Starvation soon took the heart out of the mutineers and they gave in after a final fight. When the ship berthed in New York the men who had tried to murder Samuels cheered him to the echo.

Dogged By Misfortune

In 1863 the ship’s luck turned. Until then she had never reduced sail below double-

She was put on the San Franciscan run, protected by law from foreign competition and made a number of miscellaneous voyages before she sailed from Liverpool to San Francisco in April, 1869, under new owners. At daylight on July 4 she was discovered to be among the breakers; she soon struck and was obviously doomed. Her captain and crew contrived to land on Cape Penas on the island of Tierra del Fuego.

After seventeen days of terrible hardship, living on such shellfish as they could find on the beach, they reached Cape San Diego, where they succeeded in attracting the attention of a Norwegian barque which carried them to Talcahuano, in Chile.

The news of the loss of the Dreadnought created a sensation in all parts of the world. Her fame was such that seafaring men of all the maritime countries knew of her exploits and talked of her records. Her beautiful lines had captured the imagination of many who resented the success of the steamship, and the passing of the Dreadnought seemed to them to symbolize the doom of the clipper ship.

THE SOVEREIGN OF THE SEAS of 1852, a contemporary of the Dreadnought and almost the final development of the big American clipper ship for the services to the Californian gold-

You can read more on “The Last of the Giants”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and

“Speed Under Sail” on this website.