© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Diving Adventures

Scientific experiment and research have now made it possible for men in flexible diving dresses to descend to depths as great as 300 feet below the surface of the sea. The perils that are met at such depths cannot be paralleled elsewhere.

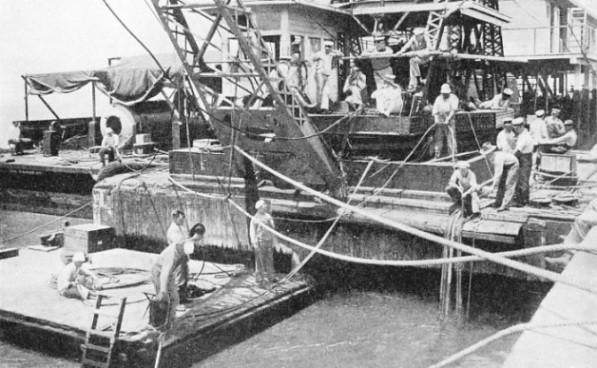

ANXIOUSLY WAITING ON THE SURFACE while divers of the United States Navy established a world’s record by descending to a depth of 304 feet. The submarine F4 sank near Honolulu, in the Pacific Ocean, on March 25, 1915. The divers went down to see that the salvage slings were in place under the sunken submarine.

IF a ship loses her anchor in the mud of the harbour, it is the diver who is sent down to search in the filth until he recovers it. If she happens to sit on a sandbank, it is the diver who is called upon to see that she has suffered no harm. If a rope has become twisted round her propeller, it is the diver who has to fight, to disentangle it.

The diver is the handy man of the shipping world, one who is called in during emergencies and expected to put everything right again. In doing his job he sometimes meets with the most hair-

A few years ago a diver who was seeking to unwind a cable from a propeller ordered the shaft to be slowly turned. To his consternation he found the men were turning it the wrong way, and before he could extricate himself he was caught in one of the loops of the cable and drawn tightly against the shaft. In a flash he ordered the men to stop -

Another diver was caught in the strangest way, because of a slight misunderstanding. He was struggling to manoeuvre a patch over a hole in the hull of a sunken ship. It was a difficult task as the patch was large and unwieldy under-

At last he got the patch almost where he wanted it, hanging over the hole but a little distance away from the side of the ship. Seeing his chance, he called to the men above to start up a pump inside the ship, knowing that directly the pump started, the sea, flowing through the hole, would draw the patch against the hull, where he could fix it.

Unfortunately for him there happened to be a number of powerful pumps installed in the steamer ready for pumping her out, and instead of one pump being started, as the diver instructed, all of them began working at full pressure. The result was amazing. In place of the gentle flow of water which the diver wanted, there was a perfect cataract through the hole. The patch was sucked against the side of the ship, leaving a slight gap. At the same instant, the diver was whisked up and sucked hard into the gap. Every second he felt that his diving dress would be split and dragged off his back. He could not move, but remained stuck to the side of the ship as a fly sticks to a flypaper.

Faced with disaster, he managed at last to send up a frantic signal and those on top, realizing that something was amiss, stopped the pumps, when the diver dropped away from the hull. He was a rather taciturn diver who generally went about his job without wasting words, but he gave tongue as never before when he was drawn up to the surface. He and his friends came to regard the incident as an amusing interlude, but it might easily have been a tragedy for the diver.

Morecambe Bay, Lancs, was the scene of a thrilling diving adventure in September 1926, when John Lee was destroying the wreck of the steamer Glencona by blowing her to pieces. He was walking circumspectly among the wreckage on the deck, taking care that his air-

The sea flooded him out instantly and an involuntary movement made him slip over the side of the ship and fall to the bottom. As he fell, the glass of his helmet struck against part of the ship and was broken. It was a dreadful position. If only the glass had been unbroken, he could have raised his head upright and continued to breathe, for the compressed air in the helmet would have kept the water down from his mouth. Now, as the air gushed out, the pressure of the sea began to crush him. As the pain doubled him up, he strove to cover the broken glass with his hands to prevent the air from escaping, and somehow managed to give the emergency signal, but only just before his senses left him.

His tender (the man on the surface looking after him) was fortunately on the alert and hauled him up without delay. Lee was bleeding and unconscious when they ripped his diving suit off him and hurried him to hospital, where he recovered.

That sudden squeeze, caused by the pressure of the sea, is a grave danger to the diver. So long as the compressed air coming down his pipe equals or slightly exceeds the pressure of the sea at the depth in which he is working, he is quite safe. If the air pressure is too great, his dress will become a little too buoyant and he experiences difficulty in keeping his feet on the bottom. To counteract this difficulty he opens his air valve to let sufficient air escape until he begins to feel a little pressure at the pit of his stomach. Then he can make his way about without feeling that he is liable to float upward at any moment.

Dangers of Pressure

A fall of twenty or thirty feet from the deck of a sunken ship might easily cause the death of a diver, for the sudden increase in the pressure of the water as he drops is not counterbalanced by any increase in the pressure of the air, and so he is crushed. It was not uncommon in earlier days to find a diver bleeding from the eyes, nose, ears and mouth when he was drawn up after a slight fall.

Many an unfortunate man has been crushed because an accident interfered with the air supply, and the balance between the pressure of the sea and the pressure of the air was not maintained.

From the earliest ages the problem of enabling a man to breathe and work at the bottom of the sea has perplexed the minds of clever men. The ancients were quite as alive as the moderns to the advantages that would accrue to them if men could be equipped to live under water while they cut sponges, gathered pearl oysters or recovered valuable articles from wrecks. But the miracle was beyond their working. It was a superhuman feat only possible to the gods. Men were therefore compelled to rely upon the skill of the natural divers who could hold their breath long enough to gather a few sponges or oysters or articles from a wreck and then come up to breathe before they made another descent.

Some of the races of native divers were almost amphibious and came of stock that had been diving and swimming in the sea for untold generations. The best of them might hold their breath for two minutes, and perhaps a few seconds longer. Their usual practice was to take a heavy stone to which a rope was attached and plunge into the sea with it.

The weight of the stone would take them down without effort, and they would thus not use energy in getting to the sea-

There are pictures more than four centuries old showing an early form of diving dress, with a man, encased in a leathern helmet and jacket, breathing through a pipe attached to a bladder on the surface of the sea. Some of these old pictures seem rather crude, yet there is no doubt that the men who invented the earliest diving dresses had a fair grasp of the problems involved. An Italian inventor who described his diving dress in 1682 made a good attempt to purify the air that the diver exhaled under the surface of the sea.

There are pictures more than four centuries old showing an early form of diving dress, with a man, encased in a leathern helmet and jacket, breathing through a pipe attached to a bladder on the surface of the sea. Some of these old pictures seem rather crude, yet there is no doubt that the men who invented the earliest diving dresses had a fair grasp of the problems involved. An Italian inventor who described his diving dress in 1682 made a good attempt to purify the air that the diver exhaled under the surface of the sea.

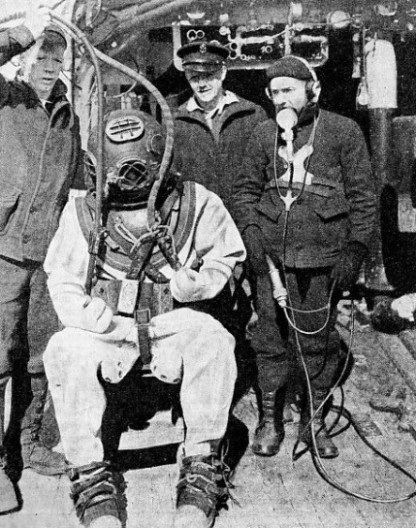

PREPARING TO MAKE A DIVE to examine the scuttled German warships on the sea-

Whether Roger Bacon in the thirteenth century invented something to enable a man to work under water, as is stated, seems indefinite; but his prophecies of the ultimate invention of the steamer, aeroplane and motor car were so wonderful that it would not seem beyond his inventive and intellectual powers to have invented a form of diving dress or diving bell.

The famous Dr. E. Halley of the Royal Society is generally regarded as the inventor of the first real diving bell in 1717. An experimental type of Swedish diving bell was already in existence in 1683, for in that year the adventurous Andrew Miller went down in one to seek the treasure from the galleon sunk off Tobermory, in the island of Mull, Scotland. He managed to recover a silver bell weighing four pounds from the ship. He also described some pewter plates and other things which he could see but not reach. The things that Andrew Miller saw were recovered more than two centuries later by Colonel Foss. Miller’s historic letter is now preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

A Devon man, John Lethbridge, made experiments in a barrel at the bottom of a well. In 1715 he devised a cylindrical dress of wood, with watertight arm-

Another century was to pass before the diving problem that Lethbridge tackled so doggedly was within sight of being solved. It was in 1819 that Augustus Siebe announced the invention of his open diving dress, fastened round the waist. The diver was supplied with air from an air pump. The dress had a metal helmet strongly resembling that in use to-

The firm that Augustus Siebe founded still exists under the name of Siebe, Gorman. Experiments are continually being made in their works. Sir Robert Davis, the head of the firm, has to his credit the invention, among other things, of the submarine escape apparatus that allowed Petty Officer Willis and several of his companions to escape to the surface of the China Sea when their ship, the Poseidon, went down in June 1931. This apparatus is now supplied to every man in the British submarine service.

Where Divers are Trained

Another invention of Sir Robert Davis was the submarine decompression chamber. This can be lowered to a great depth in the sea, where the diver may enter it and be drawn up to decompress in comfort instead of hanging about on the shot (weighted) line, as was the recognized practice.

Air pressure and water pressure, new ways of making diving safer as well as newer ways of enabling pilots to fly safely in the stratosphere, are the problems over which the experts ponder to-

The diving expert watches them through the window and shows them how to operate the air valve to reduce their buoyancy and enable sufficient air to escape to allow them to go down easily on their hands and knees if they wish to seek something on the bottom. Then he will show them how they can turn the valve to diminish the escape of air and increase their buoyancy so that they can rise without difficulty to the surface.

In this tank, powerfully illuminated by electricity, with skilled men standing above and the technical instructor keeping an eye on him outside the windows, the novice feels quite safe and soon learns to have confidence in his dress and in himself.

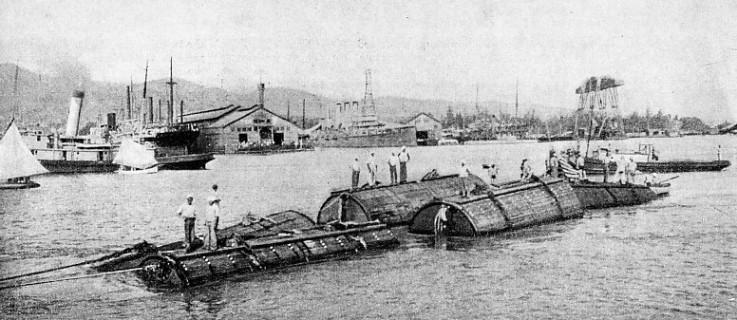

A WORLD’S RECORD DEEP-

The divers of the Royal Navy receive their first lessons in the diving school at Whale Island, Portsmouth. Here they are sent down in the diving tank to gain their initial experience in the use of the diving dress. After this they graduate to the open sea, going to greater depths as they gain in knowledge, skill and self-

It is much easier to work on dry land than to work under water, even in shallow depths, and the deeper the diver goes the greater the difficulty in working and the more his movements are slowed down by the increasing pressure. The danger, too, increases with the depth. The precautions that are taken to protect the diver may seem rather elaborate to the uninitiated, but they are absolutely essential, and it is only by following the rules laid down that the deep-

Those rules were the direct outcome of tests in which Captain G. C. C. Damant, then Inspector of Diving for the Royal Navy, risked his life along with Chief Gunner Catto to reach what was then the record depth of 210 feet in 1906. They worked at this depth and, by taking precautions which have since become standardized, they were drawn up unharmed. Once Catto’s lines got foul and he was caught for twenty minutes, but luckily he kept his head, his lines were cleared and he suffered no harm after his hazardous and alarming experience.

The effects of breathing air compressed at roughly 100 lb. to the square inch and of being subjected to a similar water pressure were most carefully studied by the late Professor J. S. Haldane. He was able to learn by his examinations of Captain Damant and Chief Gunner Catto how much harmful nitrogen the blood absorbed when subjected to air at these pressures and how long was needed to reduce the pressure and work the nitrogen out of the blood before the men could safely emerge at the surface, where the air pressure was normal.

Those bubbles of nitrogen may reach the heart and produce fatal results. They may cause permanent paralysis in the legs, deafness, double vision, intense pains in the limbs or body. Such are the symptoms of compressed air sickness, or “bends”, which used to be known as divers’ palsy. These dangers are avoided by following the Admiralty diving tables; but sometimes a diver is forced up to the surface by accident or circumstances which he cannot control. Then it is necessary to place him in the air-

In the last deep-

The fact that these were scientific tests carried out by the greatest experts who had the latest knowledge at their command is an outstanding proof of the danger that dogs the diver who seeks to penetrate the depths. Going to 300 feet subjects the human body to pressures about ten times greater than the body has to stand in normal conditions. It proves not only the courage of the man, but also the remarkable physical powers of the human body.

The fact that these were scientific tests carried out by the greatest experts who had the latest knowledge at their command is an outstanding proof of the danger that dogs the diver who seeks to penetrate the depths. Going to 300 feet subjects the human body to pressures about ten times greater than the body has to stand in normal conditions. It proves not only the courage of the man, but also the remarkable physical powers of the human body.

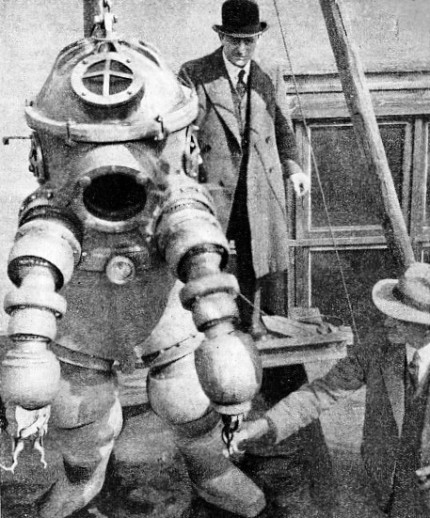

AN ALL-

It was Captain J. A. Furer, of the United States Navy, who first sent a diver in a flexible dress down to over 300 feet in an attempt, which was generally considered by the authorities as hopeless, to raise the American submarine F 4. This ill-

A search revealed a big streak of oil about a mile and a quarter from the harbour mouth, where the water was 1,200 feet deep. After having studied the oil and the air bubbles, however, the naval officers concluded that F 4 was lying much nearer shore than the bubbles indicated, and guessed that she might be in about 300 feet of water. This was a greater depth than man had ever reached before, but in the opinion of Captain Furer one not impossible of attainment.

Two of the crack divers of the United States submarine service, named Evans and Agraz, volunteered to go down to investigate. Agraz was a brilliant diver, quite fearless, who preferred to dive in a helmet unencumbered by a diving suit, so that if anything went wrong and his lines were caught he could easily withdraw his head from the helmet and escape to the surface. This practice, which was fairly common in those days, is now forbidden in the United States Navy.

Agraz and Evans, wearing only helmets, got down to a depth of 190 feet, but they failed to find the submarine. Then Agraz, still wearing only the helmet, penetrated to a depth of 215 feet, an astounding performance in any circumstances. He came up after this record dive without suffering any harm.

It was 11 o’clock on the morning of March 26 that F 4 was located by sweeping. By this time it was obvious that the crew were no longer alive. Captain Furer, however, was bent on salving her to discover the cause of the disaster, and he successfully accomplished one of the outstanding feats in salvage history -

The struggle took him five months, during which he built four pontoons, with a combined lifting capacity of 320 tons. To shackle the pontoons as close as possible to the submarine, he hit on the new idea of building two hawse pipes through them, so that the cables could be brought up these pipes near the ends of the pontoons instead of being fixed round them. It was a sound and clever improvement.

The American naval divers at that time broke the world’s record by penetrating to 304 feet to see that the cables were properly in place under the sunken submarine; but the pressure was so great that they could not work at this depth, and one diver struggled for fifteen minutes to make a simple knot in a light line. To move about in the sea at all was difficult and, as the divers ascended or descended, the tendency of the tide was to turn them slowly round and round.

Spinning round the shot rope in this way nearly cost Diver Loughman his life, for his lines became twisted when he was at 200 feet and he could move neither up nor down. When they learned how he was trapped, those above at once sent Diver Crilley to his help. Crilley struggled desperately to disentangle the lines, at the same time having to exercise the greatest care that his own did not become entangled. After two hours he managed to rescue his companion and bring him up. By that time Loughman was in a bad way, a severe attack of double pneumonia developed, and it was five months before he pulled through. He never dived again. Crilley, after his fine rescue work, hung about on the shot rope and decompressed in the ordinary way, and was none the worse for his effort.

Dressing a diver is almost a ritual. When I went diving in Scapa Flow to see the German warships after their long immersion, I first donned the regulation thick woollen socks, then heavy woollen drawers were put on and tied under my armpits over my own socks and trousers. After this heavy woollen stockings that came right up the thighs were put on, and a heavy sweater slipped over my head. On my head I wore the regulation red woollen cap, which gave me a piratical air.

Then I was helped to get through the hole in the neck of the dress and wriggle down until my feet were settled comfortably into the toes of the dress. After this a little soft soap was smeared round my wrists and I put my arms into the arms of the dress. By using a good deal of strength and not a little skill, the tight cuffs of the diving dress were induced to slip over my wrists, aided by the soft soap.

Then I was helped to get through the hole in the neck of the dress and wriggle down until my feet were settled comfortably into the toes of the dress. After this a little soft soap was smeared round my wrists and I put my arms into the arms of the dress. By using a good deal of strength and not a little skill, the tight cuffs of the diving dress were induced to slip over my wrists, aided by the soft soap.

AN AMERICAN NAVAL DIVER wears three-

The heavy boots, with their 16 lb. leaden soles, were laced and lashed on my feet. The helmet was fitted, the front glass being left open. Then the compressed air was turned on to see that pipes were clear and all was well with the pressure, which was tested by the pressure gauge.

When the front of the helmet had been fastened, I made ponderous movements to the diving ladder, down which I walked till my feet were in the water. Then I stopped while the heavy back and breast plates were fixed. When I was fully equipped in this way the weight seemed enormous and quite sufficient to carry a man to the bottom for good, for it was not easy for me to move under the handicap. The compressed air, however, which was already in my dress, made it difficult for me to duck under water. My submergence was followed by a great bubbling as the excess air was forced up in my dress and out of the safety valve.

At once the weight seemed to vanish as by a miracle. I was in another world. The sea was the loveliest shade of jade green and, as I slid down the shot rope, countless bubbles of gas, no bigger than pin points, passed ever upward all round as far as I could see. Arrived at the bottom, my feet, moving to find my balance, stirred up the sand into a dense fog that instantly obscured the diver who was my guide.

He disappeared from sight completely, although he was only eighteen inches away. Directly I stopped moving my feet, the fog of sand settled, and I followed my guide, making peculiar long steps in slow motion. A great jelly fish a yard high obstructed my path, looking for all the world as if it was some fairy tree made of glass growing in a magic land. Then I swept past it and lost it in the gloom.

Suddenly I saw what seemed to be a big fish swimming straight at me and, as I stretched out my hand to grab it, it turned aside and shot off in another direction. Instead of a fish, my astonished eyes saw a cormorant, with neck stretched straight out and wings acting as propellers, swimming fast in search of a fishy meal some fifty feet below the surface.

Now the great bulk of a battleship loomed up, with weeds growing upward all over her sides, with the guns, for ever silenced, hanging over my head in the inverted turrets. It was the greatest object lesson I have ever seen. Here were wealth and ingenuity misapplied and lying wasted on the sea-

An invisible current began to turn me round in the wrong direction, and I had to struggle with all my strength to get back again and face in the way I wished to go. Yet it was only a gentle current swirling round by a conning-

There is little to fear in British waters, but the diver in foreign seas may find himself pestered by inquisitive sharks. As a rule this dreaded scourge is easily scared away if the diver opens the air valve and lets a gush of bubbles escape.

Although divers have managed to penetrate to more than 300 feet in the flexible diving dress within the last twenty years, it is a remarkable fact that the record made by Angel Erostarbe remains unbeaten. He worked for two seasons in 1896 and 1897 to recover £10,000 of silver bars from the wreck of the Skyro, which had gone down off the Mexico reef, off Cape Finisterre, N.W. Spain. The depth he worked in varied from 171 to 186 feet, the greatest depth at which real salvage work has ever been done in the flexible dress.

T he late Sir Joseph Lowrey refused to award the contract for the salvage until he was handed some token to prove that the diver had reached the wreck. Erostarbe went down and brought up a ship’s dinner plate, which Sir Joseph retained as a valued souvenir.

he late Sir Joseph Lowrey refused to award the contract for the salvage until he was handed some token to prove that the diver had reached the wreck. Erostarbe went down and brought up a ship’s dinner plate, which Sir Joseph retained as a valued souvenir.

A REMARKABLE UNDER-

You can read more on “Dramas of Salvage”, “Raising the German Fleet” and

“Seven Years Under the Sea” on this website.