© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Britain’s Changing Coast Line

The loss of land due to the encroachment of the sea is serious and spectacular. The principal cause is the combined action of waves, tides and currents. Various measures have been devised to deal with the problem, but they have to be applied with prudence and caution

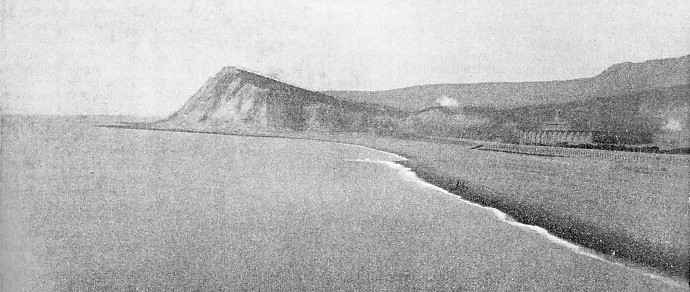

SHAKESPEARE CLIFF at Dover, Kent, now 350 feet high, was once much higher and more prominent than it is to-

COAST erosion and the allied subject of coast accretion make a fascinating study which does not receive nearly as much attention as it deserves.

From time to time big cliff slides are reported, or the summer visitor sees where the sea has gnawed a huge mouthful out of the land. There is a general tendency to think that the British Isles are steadily disappearing, although so gradually that the process must take thousands of years.

The balance, however, is in the other direction. Between 1875 and 1900 the Ordnance Survey showed that about 4,692 acres were lost in England and Wales and 35,444 acres were gained, a net gain of over 30,750 acres. In Scotland during the same period the gain was 3,889 acres, and in Ireland 6,721. This included natural and artificial accretion. It is also surprising that the agricultural land which is gained is often of more value than the land washed away, especially if the accretion is protected by walls.

Although the balance is favourable, can prevent the impression of steady loss. The erosion is generally intermittent, always conspicuous and sometimes dramatic, and occurs almost entirely on the open coast where it can attract the most attention. The growth of land, on the other hand, is almost entirely in tidal estuaries and bays, and is so slow that the conversion from marsh to valuable grazing land is almost unnoticed.

Erosion is a serious concern to the authorities, but there is an unfortunate confusion of authority. The Board of Trade is the manager, on behalf of the Crown, of most of the foreshore in the United Kingdom. Where the Board does not act as manager of the foreshore it acts only in the interests of navigation.

The Board of Trade has certain limited powers of veto inherited from the Admiralty under the Harbours Act of 1914, but has no funds to carry out works. The Ministry of Agriculture is interested, and also the Catchment Boards under the Land Drainage Act. The influence of the Ministry of Health arises through local authorities borrowing money. The Ministry of Transport is concerned where there is a road to be protected. The Commissioners of Crown Lands are the owners of a large part of the foreshore, and local authorities and property owners are intimately concerned in the matter.

It has been decided that erosion is primarily a local affair, and, in the absence of Government grants, local authorities who cannot afford expensive sea defence works have had to watch villages disappear, as happened to the village of Amroth, on the Pembrokeshire coast.

Arrangements for dealing with accretion depend on circumstances. If the gain is “gradual and by small degrees” it goes to the adjoining landowner, but if it is “sudden and considerable” it belongs to the Crown as the normal owner of the foreshore.

The matter occupied the attention of a Royal Commission from 1906 to 1911. The commission examined every point with the greatest care, and finally issued voluminous reports which, if they are not exactly light bedside reading, are at least fascinatingly interesting and contain a mass of detail on a subject about which all too little is generally known.

So far-

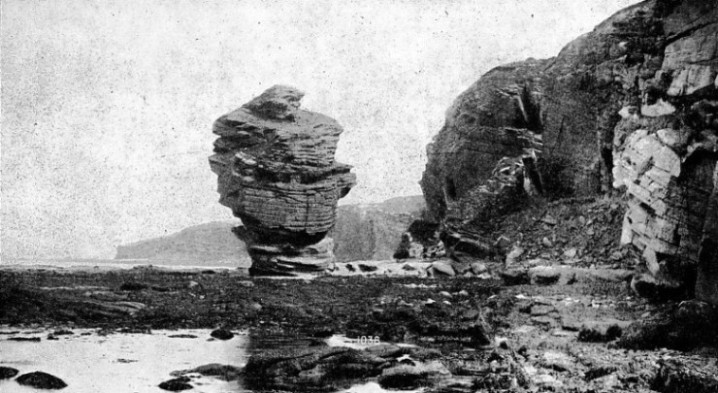

Coast erosion has been going on for many thousands of years, ever since the British Isles were formed, and before that to the very dawn of geological history. Most of the boldest headlands round the coast must have been the result of erosion round them in the distant past. The patches of harder rock have survived where the softer material on either side has been weathered away, and the ragged outline of the land which faces the mighty force of the Atlantic is due to the same cause. For the most part, however, it is only necessary to go back a hundred years or so to find plenty of dramatic instances of land being overwhelmed by the sea.

On the coasts which are particularly exposed to the force of the Atlantic the process of erosion is especially conspicuous. Early in the present century hundreds of acres of rich pasture land

at Youghal, Co. Cork, were flooded through a breach in the shingle ridge which protected them. On various occasions since then, however, successful reclamation work has caused a considerable accretion of useful land in this area.

On the Cornish coast, St. Michael’s Mount, now cut off from the land except for a small causeway, is believed once to have been a granite mass rising out of a swampy wood. Erosion on the Cornish coast is slow, due to the hardness of the rocks, even in spite of the force of the Atlantic, but a tremendous amount has taken place in the past, and in places there is still danger.

Lost Land of Lyonesse

The mysterious Land of Lyonesse, constantly mentioned in the legends of King Arthur as being under the rule of the wizard Merlin, is supposed to have existed between Land’s End and the Scillies. Although the details of Lyonesse are fabulous and its extent greatly exaggerated, there is certainly a substratum of truth in the story of large areas of land lost to the sea.

In North Devon, too, there has been considerable loss. There is every evidence that the land at Bideford Bay once extended far out to sea. Much land has been lost between Minehead and the mouth of the River Parrett, Somerset, within recent years. The trouble here had been made worse by the landslides and by the removal of limestone for industrial purposes.

The famous pebble ridge at Northam and Westward Ho, Devon, familiar to every reader of Kipling’s Stalky and Co., is the most remarkable shingle beach on the west coast. It is over two miles long and protects a large tract of low-

The beach is conspicuous by the large size of the boulders which go to make it up, most of them the waste from the cliffs along the coast to Hartland Point. Normally these boulders form the finest protection possible, provided by Nature herself, but when they are breached, as they were in 1926, the effect is exceedingly serious.

TO CHECK THE ACTION OF THE SEA, in an attempt to preserve houses situated close to the shore, members of the Kessingland (Suffolk) lifeboat crew are shown building sea defences. A trench has been dug and the men are burying faggots in it, to bind the soil together. The sea has made many inroads on this part of the East Anglian coast.

All along the northern coast of the English Channel the problem has to be faced in some form or another, sometimes seriously, sometimes as a comparatively minor matter. On the Strait of Dover erosion and accretion are major concerns. In the matter of accretion Romney Marsh, Kent, is a wonderful tribute to the enterprise and scientific care of our forefathers.

The Marsh was “inned” in Roman times. A huge area of shallow water and useless marshland made the finest grazing land in the country, with the mighty Dymchurch Wall running for miles along the coastline as a trusty guard. This wall has been greatly strengthened by the building of groynes outside it. These have had the effect of checking the drift of shingle and sand and building up an outer natural defence at the foot of the wall.

The finest possible prevention of coast erosion is the one provided by Nature herself, a protecting belt of shingle or sand at the foot of a cliff, against which the waves break their force. Groynes, the erections which are popularly but incorrectly known as breakwaters at every seaside resort, are built of wood, stone or concrete to catch the shingle, and sand as it moves along the coast. Thus they form a sound defence on that particular strip of coast-

The materials which protect the base of the cliff are shingle — stones of various sizes — and sand. It is curious that as they are derived entirely from the erosion of the land, a certain amount of erosion is necessary to supply the material to the beach for the protection of the land. Shingle and sand are always on the move and with the inevitable friction are always getting smaller in their particles. The finer materials appear to be carried out to sea and lost entirely, but the shingle and sand last for long periods.

It is, therefore, most important in coast defence to study carefully the drift of material. It is not an easy matter, for there are innumerable local influences at work. Normally the drift follows the path of the flood tide and the net drift is remarkably constant.

On the south coast of England the drift is from west to east. On the east coast, from the River Tweed to the Thames, the drift is from north to south. On the west coast it is from south to north as far as Morecambe Bay, Lancs, but north of that the drift is from north to south. In Scotland on the southwest coast it is from west to east, on the west coast from south to north, on the north coast from west to east and on the east coast from north to south.

Those, however, are only the general principles and there are constant variations. Many of these are due to the wind, but some are stable, due to local circumstances. In many bays, for instance, the shingle circulates round and round but does not leave the bay at all, the general drift passing outside it. The drift is most considerable and most easily recorded between high-

Castles Engulfed by the Sea

Therefore, while immense use can be made of this material for the protection of the cliff, it has to be carefully dealt with or it will cause trouble. Henry VIII built Deal, Sandown and Walmer Castles a quarter of a mile from the shore, which was composed of shingle and seemed to offer an impregnable defence against the sea. Then he built his big pier at Dover, the beginning of the huge national harbour. This checked the natural drift and piled it up along the Shakespeare Cliff. The shingle protection to the three castles began to disappear, and the building of the huge harbour, offering a complete bar to the drift, has completed the trouble. Sandown Castle has long disappeared into the sea because of the previous harbour works, and the other two castles are right on the edge of the land, although they are now protected by the shingle collected by the groynes which have been put up by local authorities.

Close under the lee of Dover Harbour, however, there is no space to collect beach material to compensate for that washed away, and the erosion and cliff falls at St. Margaret’s Bay and Kings-

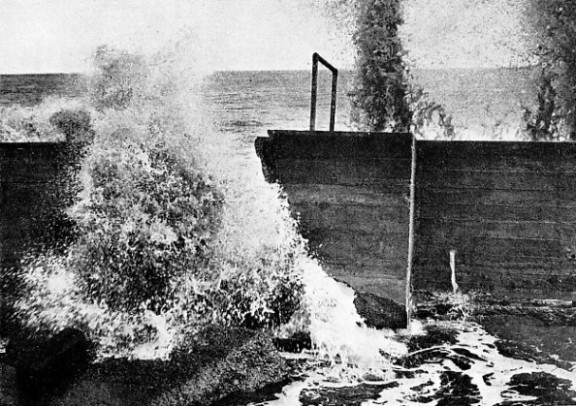

THE RELENTLESS SEA entering a breach in a newly-

Opinions are divided as to whether the Goodwin Sands are an example of erosion or of accretion. Many people are familiar with the legend of how the sins of Earl Godwin caused the fertile land of Laumea to be engulfed by the sea. If there is any truth in this story, this is an instance of the results of neglect in coast protection. There are also many who believe that the sands have been caused by the peculiar currents all round them collecting material from the sea-

A little farther round the coast of Kent, the Reculver Towers, near Herne Bay, were once well over a mile inland. That stretch of coast has always been specially subject to erosion, although the final ruin of the Saxon Church to which the Towers were attached was due to the vestry selling to a company which proposed to build a pier at Margate the stones of the sea-

Herne Bay, a short distance west of the Reculver, has been deeply bitten into and the Isle of Sheppey more deeply still. It is estimated that the present island is only about two-

Submerged City

The greater part of the East Anglian coast is even more susceptible to erosion than Kent. It is generally believed that when the land stood at a relative level of about 60 feet higher than it does now, most of the east coast was surrounded by a belt of low-

Almost the whole of that coast of England still demands constant attention to prevent erosion. It has received such attention for many years past, sometimes with and sometimes without success. The famous Roman post of Bradwell, in Essex, one of the most important protected ports in the country in its day, has been overwhelmed by the water. Many other seaboard towns have either shared its fate or else have been saved only by huge effort.

At Aldeburgh, in-

Perhaps the most interesting, and certainly the most frequently described instance of erosion is that of Dunwich, Suffolk, formerly one of the most important cities in East Anglia, but now completely submerged by the sea. The erosion on this part of the coast has not been regular.

For some periods, the erosion has been disastrous, and these have always been followed by others in which little harm has been done. It is suggested that the movements of the outlying sandbanks have had a good deal to do with this, but, although much good has recently been done by rows of faggots placed in the sand and bound together by marrum grass, the district is particularly difficult to protect because of the nature of the ground.

IN THE FALKLAND ISLANDS. The encouraged growth of rice-

Our forefathers had no knowledge of modern scientific protection and the town had to go. The bishopric there was founded in the year 630 and there is still a Suffragan Bishop appointed to-

As in almost every other part of the coast where erosion has submerged a town, there are many local legends about the church bells being heard from under the sea on certain occasions.

Round about Lowestoft, Suffolk, there has been a good deal of trouble in the past. Erosion at Lowestoft itself was attributed to defence works at Corton checking the drift of shingle. So Lowestoft looked after its own interests and put up such efficient groynes that at Pakefield, near by, no fewer than three sea-

A hundred years ago the town of Cromer, Norfolk, was in the gravest danger of being swallowed as Dunwich had been. A fierce storm in 1836 breached the beach defences and threatened not only the town but also the hinterland.

Temporary steps were immediately taken, and in 1845 the protection of the district was definitely placed under the control of the Cromer Protection Commissioners, who built a sea-

Under a further Act of 1899 the Commissioners continued to function — the pier is part of their responsibility — but their activities have caused a considerable amount of trouble farther round the coast.

Reclamation of 32,000 Acres

In the Wash the trend of events is reversed and there has been great accretion. In the earliest days the Wash was much bigger than it is now, the reclamation being largely natural but greatly helped by the walls and banks which have been built at various times since Roman days.

In 1846 there was a great increase in activity. The Norfolk Estuary Company obtained an Act of Parliament permitting the reclamation of 32,000 acres. The company undertook to build a new channel four miles long connecting the port of Lynn with the sea. The cost of the work was more than £230,000, but the liabilities of the company were heavy and to reclaim the land cost about £25 an acre, only about 2,200 acres having been saved by 1910.

Similar reclamation work on the River Humber, which contains more silt than any other river in England, was begun in the reign of Charles II. Round Sunk Island a total area of about 7,000 acres has been converted from waste into rich arable land, first by the efforts of private owners and then by the Office of Woods and Forests.

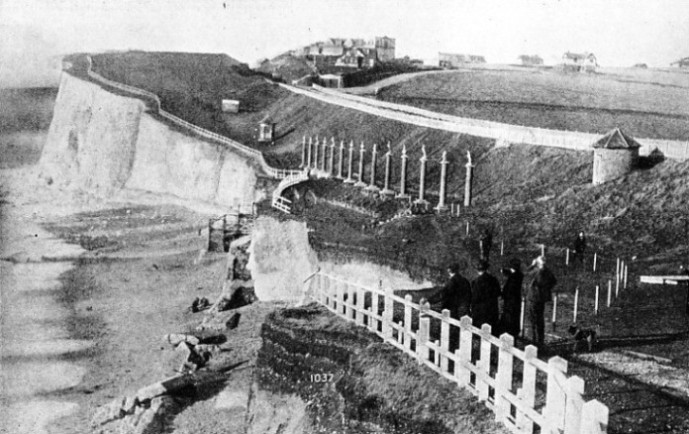

ENCROACHMENT IN SUSSEX. Two gaps have been formed by heavy seas in the cliff walk at Saltdean, eight miles east of Brighton, on the main coast road to Eastbourne. The sea wall also has been destroyed and its fragments are lying on the beach at the foot of the cliff. All round the coasts of Great Britain erosion, balanced by accretion, is going on. Contrary to the general belief, more land is annually won from the sea than is lost by its encroachment.

North of the Humber there is another stretch of coast where erosion is bad. Holderness, between Spurn Point and Flamborough Head, Yorks, has been subject to excessive erosion for centuries, vying with East Anglia for the doubtful privilege of being the most serious instance in Great Britain.

Twelve towns and villages are known to have been washed away. Ravenspurn was an important port when Henry IV landed there in 1399. Edward IV in 1471 also landed there on his return from exile, but the town has now disappeared. Between 1848 and 1893 no fewer than 774 acres in this area were lost. This is the position all round the coast, erosion here and accretion there, but naturally the individual, or the community, is more concerned with the disappearance of his land from under his eyes than with the gain which is gradual and almost imperceptible.

The principal cause of coast erosion is the action of waves, tides and currents combined, with the waves as the dominant factor. Their hammer action has been shown by observations in some parts of the coast of Scotland where they showed a pressure of three or four tons to the square foot. Despite this, the waves themselves have little effect against hard rock. The debris and material which they throw against the face of the cliff do the most damage.

Cliff slides occur for a variety of reasons. Hard material over soft always has a tendency to move, and the weight of a high cliff will often cause trouble by breaking down its foundations of clay or sand, or even of rock. Ill-

This remarkable plant, which is an accidental hybrid of mixed British and American origin, was first found growing in Southampton Water, where it had apparently been started by seeds accidentally dropped from some ship.

Complicated Sea Defences

It was discovered to be an excellent material for checking erosion and for binding the sand. It will flourish even where it is covered by four or five feet at high water, but in Great Britain never grows above high-

The placing of groynes may do immeasurable harm to adjacent property and their design is difficult to determine. Concrete groynes are expensive, especially in view of the difficulty of finding a sound foundation, and their life is problematical. If they are not well cast groynes will not last for long, and once a concrete groyne is built it is difficult to alter when experience suggests the desirability. Plank groynes built of stout timber are preferred in many places, for it is easy to build them from two to three feet above the beach only, which checks erosion on the other side, with their piles left long enough for them to be built up as the shingle or sand collects.

Similarly sea walls may prove an excellent protection or they may be so much money thrown away. There are several types, of which the principal are the step type, the batter type, or a compromise of the two to deal with the effects of a critical state of the tide, and finally the curved type. Each design has to be chosen for the conditions which it combats, and the conditions are always liable to change. Generally a sea wall is supported by a number of small groynes, but some are successful without them. The undermining of the base of the wall by the action of the water is the principal cause of trouble with that type of defence.

All sea defences have to be constantly examined, for the least sign of failure and neglect of this causes great trouble and often disaster which proves irreparable. The sea defences of the country are the care of a number of experts whose work, almost unknown to the general public, cannot be praised too highly. Unfortunately, they are hampered sadly by the present state of the law and the division of responsibility which often prevents definite and well-

BEYOND THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS. The Castle Rock, Hopeman Bay, Moray, near the fishing villages of Hopeman and Lossiemouth, is an excellent example of the survival of hard rock after the sea has washed away the softer material. Most of the boldest headlands round the coasts of Great Britain must have been formed by erosion in the distant past. The process has been going on for untold years from the dawn of geological history.

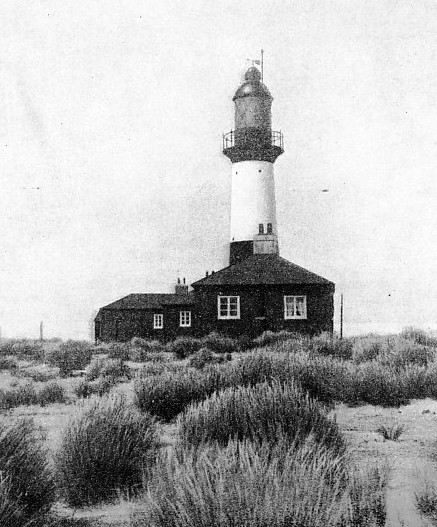

You can read more on “Pilots and Their Work”, “The Restless North Sea” and “Signposts of the Sea” on this website.