© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The “Chelyuskin” Rescue

For the first time in history wireless and aviation were responsible for the rescue of an Arctic expedition when in 1934 Russian aeroplanes saved the lives of more than a hundred men, women and children stranded on the Polar ice pack, after the sinking of the ill-

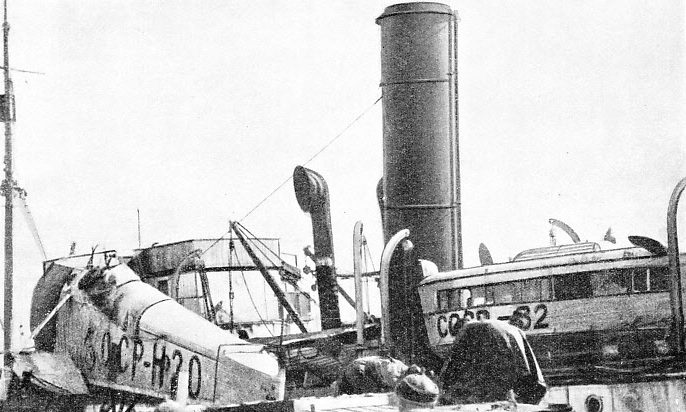

THE ARCTIC OCEAN was the scene of the wreck of the Chelyuskin and of a remarkable rescue by aeroplane. In August 1933 Professor Schmidt and a party of scientists sailed in the Chelyuskin in an attempt to prove that an ordinary cargo vessel could voyage through the North-

THE conquest of the Arctic Ocean has long been the dream of mankind. As far back as the sixteenth century brave men felt the lure of the Polar regions. Many English sailors attempted to reach the Pacific Ocean by a northern route.

The expeditions of Willoughby and Chancellor in the middle of the sixteenth century reached only as far as the mouth of the river Dvina, where Archangel now stands. Willoughby and most of the members of his expedition perished from the privations they endured. Their ships were found gripped in the ice-

During the succeeding centuries scientific explorers studied the Arctic and Antarctic; but as yet no one had discovered the North-

In 1878, however, Nordenskjold set out from Gothenburg (Sweden) in the small ship Vega, and reached the northernmost point of the Old World, Cape Chelyuskin in Siberia, which had for centuries been the goal of unsuccessful struggles. A week later the mouth of the river Lena was safely passed. There were good prospects of completing the voyage in one season, but towards the end of September the weather intervened. The Vega was frozen in the ice and securely imprisoned for the winter. The vessel survived the ordeal and when release came in the following July the Vega had been frozen in for 294 days. On July 20, 1879, the Vega passed the Bering Strait. Nordenskjold joyfully declared: “After a lapse of 326 years, when the gallant Englishman Sir Hugh Willoughby made the first attempt at a North-

The Vega finally arrived at Stockholm on April 24, 1880, after a voyage of 22,189 miles.

Death Intervenes

While the Vega was passing through the Bering Strait, an American expedition, in the Jeanette, equipped by Mr. Gordon Bennett, steamed out of San Francisco harbour to attempt the voyage from the Pacific to Europe through the Bering Strait. Sixty days after she had left San Francisco the ship was wedged in the pack ice. Three whaling vessels later reported the Jeanette in the neigh-

After having been trapped in the ice for twenty-

Meanwhile the leader, De Long, had landed with twelve men, and set out for Bulun, a settlement on the Lena. One after the other the men died from weakness. Two of the strongest men were sent ahead for assistance, and eventually found some natives out-

The next day, November 2, 1881, as they lay on their crude beds, too miserable to move, a man dressed in furs looked in. For a moment they did not recognize him. Then he spoke to them. It was Melville, the ship’s engineer.

“We thought you all had perished!” exclaimed Noros, one of the men sent on ahead.

“Where is De Long?” asked Melville anxiously.

“We left him travelling southward towards Bulun”, was the reply.

Melville set out with native guides, dog teams and provisions. Through blizzards he pursued his search, travelling more than 600 miles; but he could find no trace of De Long. Winter passed and a relief expedition sailed from America. The relief ship caught fire off the coast of Siberia, but the relief parties found Melville and Noros. The search for De Long continued. Suddenly, on a March day, the discovery was made. Melville tells how he saw a tea-

Melville recognized them as Captain De Long, Doctor Ambler and Ah Sam, the cook. Seven miles away, at the top of a bold promontory overlooking the Polar sea, De Long and his brave comrades were buried. The relief party erected a cairn over the bodies, and made a cross from a spar. After two years De Long and his comrades were brought home to America in 1883 by the order of the Government and given a final resting place with military honours under their country’s flag.

Amid the wars and revolts, the famine and fears which gripped the new Soviet Union after the two Russian Revolutions of 1917, the North-

The Government put everything necessary at the disposal of the scientists -

Ambitious Planning

In 1929, the second year of the Five-

They collected rich scientific material, and gave the world a better knowledge of weather conditions and of the laws and movement of ice-

In 1932 the Soviet Union scientists already possessed sufficient information and experience to follow with new force the old aim initiated by the Englishmen of the sixteenth century -

Professor Otto Julius Schmidt set himself the task of making the North-

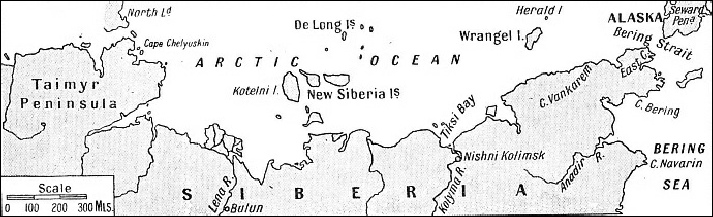

UNLOADING THE SEAPLANE FROM THE CHELYUSKIN. For reconnaissance purposes, the expedition took a small seaplane on board. It was soon after this seaplane had reported open sea, six miles ahead, that the pack ice finally held the Chelyuskin in its relentless grip and carried her far northward to destruction.

After calls at several points on the route, the expedition proceeded to the mouth of the River Lena, and reached open water in the neighbourhood of the Taimyr Peninsula. A visit was made to the scientists at the research station on Tiksi Bay. Then the Sibiriakov escorted two cargo steamers as far as the Kolyma Eiver. The ice conditions were dangerous but not impossible, and all three vessels reached that point safely.

The expedition continued on an easterly course, and shortly encountered heavy pack ice. Conditions were similar to those which had held up Nordenskjold sixty years before. A smashed propeller was repaired, and once more the Sibiriakov went ahead and came up to more heavy pack ice. Once again the propeller was jolted by the pack ice and broken. Further repairs were out of the question, and the vessel began to drift helplessly with the current. The hardy Russians improvised a temporary sail, and this enabled them to make slow progress. The Bering Strait was reached in October, two months and four days after the vessel had left the White Sea. There the crippled ship was taken in tow by a trawler, and the expedition reached Yokohama on November 5. The North-

Heartened by the success of the Sibiriakov, Professor Schmidt organized a second expedition to discover whether ordinary cargo vessels could voyage through the North-

Only Six Miles from Safety

On August 8, 1933, this expedition set forth in a stoutly built vessel called the Chelyuskin. Aboard her were not only explorers and crew, but also a group of famous scientists. One hundred and three people were in the vessel, including ten women and a baby. A second baby was born during the voyage. The vessel, having reached Wrangel Island, took off a party of scientists that had been left there some months before. The Chelyuskin now steamed eastward through hundreds of miles of pack ice, beset by blizzards, storms and fog. Then came the day when the little seaplane carried by the vessel rose into the Polar air for a reconnaissance flight. The seaplane returned with the tidings that open water lay ahead, barely six miles distant.

They were six miles from the Pacific and their goal. Had the Chelyuskin traversed the distance that separated the vessel from open water, it is probable that her name would not have been given to a story which is one of the finest epics of Polar exploration. The world might never have heard of either the ship or her mission.

In Polar regions, as explorers know, anything may happen in a few minutes. The Chelyuskin was destined never to reach ice-

When success was in sight the gentle breeze developed into a raging blizzard blowing straight off the distant coast. The ice pack, several feet thick, piled up and drifted in a northerly direction. Within a few hours the Chelyuskin was as securely cut off from the open sea ahead as if she had been at the Pole itself.

Wedged between hard-

There was only one hope of salvation, and that was the radio. In January 1934, after the long Polar night had set in, listeners in the radio watch-

In simple words Professor Schmidt, the leader of the expedition, gave the news of its plight. He reported that all were then in good health, but that their vessel was trapped and that the Chelyuskin was in danger of being crushed by the pressure of the surround-

More messages were received during the three long months that followed, and each message came from farther northward as the trapped adventurers were carried slowly and relentlessly away from human aid.

THE DANGERS OF THE ICE PACK were constantly harrying the Chelyuskin expedition during its long sojourn on the drifting ice of the Arctic Ocean. Fissures would suddenly appear without warning, and this photograph shows how on one occasion a fissure cut completely through one of the huts in the camp.

There could be only one conclusion to that vigil with death. The end came on February 13, 1934. The pressure of the ice round the Chelyuskin tore out one side of the vessel and sent her to her doom.

A final catastrophe was averted by splendid discipline and foresight. During the drift, officers and scientists had prepared to abandon ship. When the time came and the ship was slowly sinking, everything movable, including stores, scientific instruments and wireless apparatus, was passed out on to the ice floe. Then the world heard the news that the Chelyuskin had gone and that one hundred and four persons were marooned on floating ice somewhere in the Polar wastes.

To the men and women huddled on that drifting mass of ice the radio S.O.S. must have seemed a forlorn hope, yet their moral was unbroken. As soon as the ship had gone, the men set about the task of erecting a hut for the women and children, to shelter them from the blizzards and intense cold. After that, they built shelters for themselves, and settled down to wait patiently for rescue -

The leader wirelessed that he had sufficient rations for two months and sufficient oil for lighting and heating. He added that within two miles of the camp was a flat stretch of ice where aeroplanes could land in good weather.

On the mainland, active preparations were made to rescue the expedition. The famous ice-

Every morning at six o’clock, Professor Schmidt sent wireless messages to Moscow reporting on the position. Breakfast followed at eight o’clock. During the day working parties were kept busy improving the camp and heating arrangements. The women were always busy mending clothes or cooking. Dinner was taken at noon, and another meal at eight o’clock in the evening.

Rescue by Air

Professor Schmidt frequently delivered lectures in the evenings. He would call all hands together and read out the wireless messages that told of the preparations made by Stalin for their rescue. No cheering messages, however, could alter the fact that they were drifting northward every day.

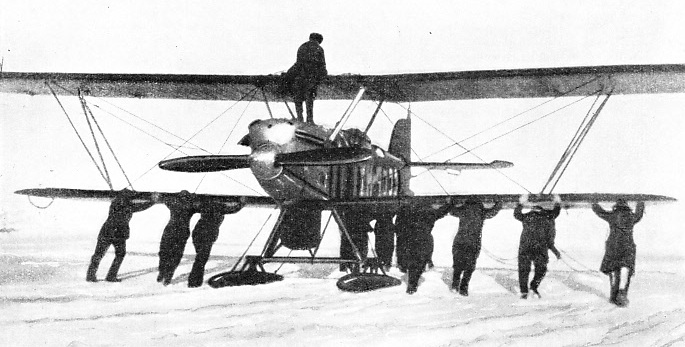

The rescue was effected by a small group of Soviet airmen, including four young men named Lapedievski, Sliepner, Kamanin and Molokov. Molokov was a pilot employed in the Soviet Air Service. He and Lapedievski read the wireless messages from the stranded expedition and volunteered to go to the rescue. Their offer was accepted by the authorities, and the aeroplanes were ordered to air bases, at Capes Vankarem and Weller, on the Siberian coast, about one hundred miles from the marooned expedition. Those with knowledge of flying at the Siberian aerodromes must have told them they were attempting the impossible. They had to fly a distance of only one hundred miles either way, but every inch of that journey lay over ice-

Before their water-

It was in March, three weeks after the sinking of the Chelyuskin, that the miracle happened. The men and women trapped in the Arctic silence suddenly heard a strange sound from the skies. Rushing out of their primitive huts they saw an aeroplane circling overhead.

The airman looked for a flat place where he could land without wrecking his machine. At last he was down -

The age-

Meanwhile, the other rescue detachments were making their way northward in the face of terrible obstacles. They were delayed at one aerodrome for five days by a fierce blizzard which buried their machines in ten feet of frozen snow. “The petrol is not only unfit for aeroplanes, but would be dangerous to use even in a tractor”, wrote one of the pilots in his diary.

At last Kamanin and Molokov reached Cape Weller. A third machine arrived at Cape Bering and a fourth landed in a fog before reaching the coast. The mechanic of the fifth aeroplane reached Anadir, frost-

On April 6, three pilots -

An Arctic Miracle

It was a miracle that Molokov’s machine rose into the air at all with its load of seven, but once in the air the little engine carried them to safety. Molokov returned on the next day and was able to take off six more of the marooned explorers.

By April 10 Sliepner had repaired his machine, and he flew to the mainland with a cargo of ten men. That same day Kamanin and Molokov rescued another seventy-

On April 13, daybreak brought the last three rescuing aircraft piloted by Molokov and two comrades. The last of the stores were loaded on board. Then Camp Schmidt sent out its final radio to the world: “April 13. Radio stopping. In half an hour, I, Captain Voronin and Wireless-

Every single soul was rescued, and even the dogs were saved. The scientific instruments were brought to the mainland, and nothing of value was left behind.

Modern courage -

For their heroism in carrying out these rescues the Soviet Government awarded special decorations to all concerned. Molokov, Lapedievski and Sliepner received, as a special recognition, a holiday to London.

Thus the Chelyuskin and her crew endured all the perils and hardships of Arctic exploration to add another chapter to the annals of navigation.

AN ARCTIC AEROPLANE is specially fitted with skis for landing on the ice and snow. This photograph shows a Soviet Russian aeroplane before a reconnaissance flight. It was in aeroplanes of this type that the members of the Chelyuskin expedition were rescued. The aircraft were operating from the base aerodromes at Capes Vankarem and Weller on the Siberian Arctic coast.

You can read more on “Adventures of the Ice-

“The North Atlantic Ice Peril”on this website.