© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Yokohama

Symbol of the changing East, Yokohama has developed in a hundred years from a fishing village to a port that handles more than three million tons of shipping annually

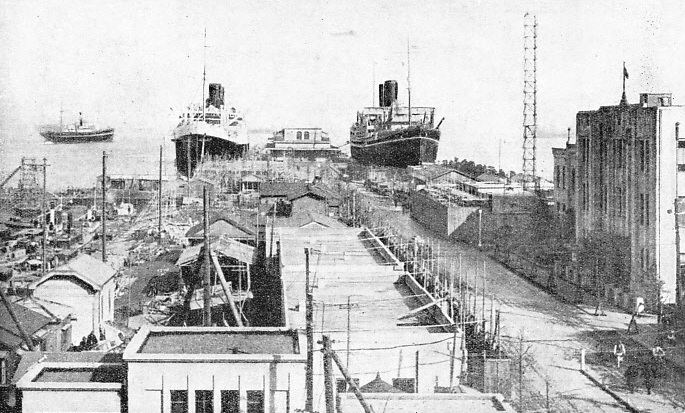

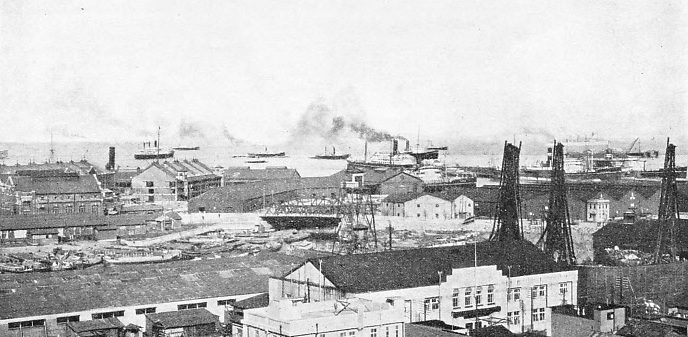

THE GATEWAY TO THE CAPITAL OF JAPAN. Yokohama is only some eighteen miles from Tokyo, the capital, and transport facilities between the two cities are excellent. The harbour affords good and safe anchorage for vessels of any size which can load or discharge at the quays, piers or buoys. There are also wet and dry docks and shipyards, with facilities for repairs and overhaul. In one year 3,456,000 tons of shipping entered Yokohama and 3,359,000 tons were cleared.

IN a few moments at noon on September 1, 1923, the great city and port of Yokohama, Japan, was shattered by an earthquake. Fire swept the city. About eighteen miles away, Tokyo, the capital, was devastated by the same earthquake. The Japanese were faced with a terrible loss of lives, an appalling roll of injured, and the task of rebuilding their capital and their famous port. A reconstruction bureau was set up, the ruins were cleared away, and on their sites arose still greater cities, built on a new plan.

The seafarer entering the port of Yokohama sees before him a monument to the courage, engineering ability and resource of the Japanese. All is new, and the port is growing steadily -

Yokohama is the port for ships from the West and East. Before the arrival of the white man, less than a century ago, there were a few score of poor fishermen’s homes huddled together. When the modern city was rebuilt after the disaster of 1923 it had an area of 50·87 square miles; in 1934 the population had grown to 703,900, including foreigners, from the total of 442,600 eleven years before. It took some six years for the Government and the municipality to reconstruct the city and the breakwaters, piers and equipment of the harbour. The boundary was widened to bring in neighbouring towns and villages, so that the area is about three times that of the old city.

One of the best known and most used of modem ports, Yokohama is either a terminal or a point of call for a number of great steamship lines which link it with capitals as far distant as London and New York. It lies on the west side of Tokyo Bay, and is approached from the Pacific through the Uraga Channel. Vessels, whether from Great Britain or from America, approach through this channel, which lies between the Miura Peninsula on the west and the Boso Peninsula on the east. In clear weather the majestic cone of Mount Fuji can be seen rising 12,467 feet into the sky. To the south is the volcano of Mount Mihara, on the island of Oshima.

As the vessel nears the entrance to the Bay of Tokyo, the town of Uraga, where the modern history of Japan began, is to port, and later the naval base of Yokosuka opens out. Here are naval dockyards, and the battleship Mikasa, flagship of the Japanese Fleet at the time of the Russo-

A NOVEL METHOD OF COALING at the port of Yokohama. Coal is handed up from the barges at the side of the ship by scores of workers who form living conveyer bands. This illustration shows men and women “coal-

Soon the passengers see the masts and funnels of the ships lying in Yokohama Harbour. A new outer breakwater that, at the time of writing, is being built is nearly completed. After the medical authorities have given her pratique, the ship passes through a gap in the inner breakwater to her berth. Tokyo lies at the head of Tokyo Bay, about eighteen miles from Yokohama, but the bay shallows. Much dredging has been done recently, and 6,000-

Yokohama Harbour affords good and safe anchorage for vessels of any size, which can load or discharge at quays, piers or buoys, and there are wet and dry docks and shipyards, with facilities for repairs. The port opens to the southeast. Low hills to the south-

Rival Ports

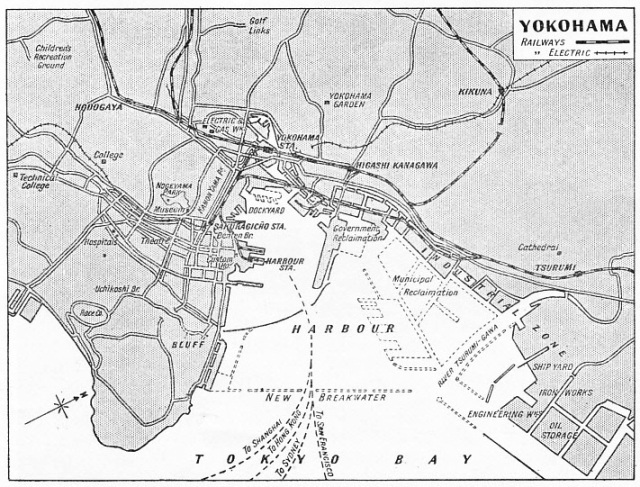

The inner breakwaters extend in a curve from north to south so that the inner harbour, of about 1,121 acres, is well protected. The new outer breakwaters have been designed to give an additional sheltered area of some 2,040 acres.

The channel leading between the north and the east breakwaters of the inner harbour has been dredged to a depth of over 40 feet, and there is a lighthouse on either side of the entrance to the inner harbour. Quays along the embankment already afford berths for seventeen ships, as follows -

6,000 tons, and three of 3,000 tons. A long pier projects from the south-

Half of the eighteen-

Half of the eighteen-

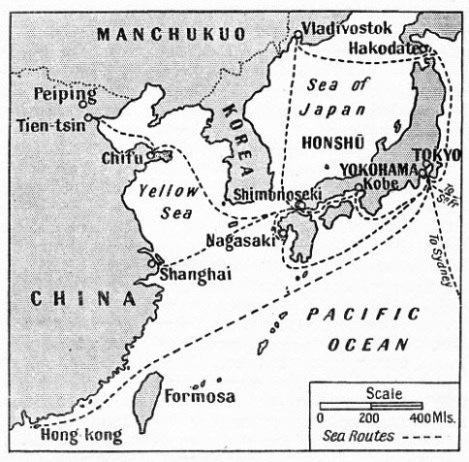

OF PARAMOUNT IMPORTANCE to the industrial life of the Japanese Empire, the port of Yokohama is clearly indicated on this map. Near the entrance to the Bay of Tokyo is a big naval centre where there are many dockyards.

The biggest floating crane lifts 120 tons, and there are five others which lift from 30 to 100 tons. The wet dock of the Yokohama Dock Company is 600 feet long and 180 feet wide, and the same company’s dry docks are -

As the region comprising Yokohama and Tokyo is one of the most densely populated in Japan, the port is one of the busiest in the country. Its rival is Kobe, which, as with Yokohama, is of mushroom growth, and is the larger. After the earthquake Kobe secured much of the trade, but Yokohama soon recovered. It is the natural gate to the capital and is a portal through which have flowed those Western ideas which have changed much of Japanese life.

Uraga, on the west side of the entrance to Tokyo Bay, was the scene of the landing of Commodore Perry of the United States Navy in the ’fifties of the last century. After his landing a treaty was signed and a part of the foreshore of what is now Yokohama was leased to foreigners. The town, thus founded, began to grow from 1859, but eight years later was swept by a disastrous fire. At that period there were only two mail-

The first railway in Japan was that between Yokohama and Tokyo. The coastal shipping trade had been fostered, and foreign and Japanese banks concentrated at Yokohama as the great port of enterprise. A ten-

A PLAN of the city and port. The inner breakwaters extending in a curve from north to south provide about 1,121 acres of protected water; the new outer breakwaters have been designed to give an additional sheltered area of about 2,040 acres. Considerable dredging has been carried out in the harbour; the channel between the north and east breakwaters of the inner harbour has been dredged to a depth of over 40 feet.

Then disaster came. A few minutes before noon on September 1, 1923, the earthquake occurred. In every little home in the town the housewife was preparing the mid-

The landing pier collapsed, nearly all the quay walls were damaged, part of the breakwaters crumbled and disappeared under water, sheds and warehouses tilted and caught fire, cranes toppled into the harbour, and the work of many years lay ruined. Ships in the harbour came to the rescue of people on shore by taking refugees to other ports and by landing supplies.

Within two months of the catastrophe, on October 20, the enormous task of reconstructing the harbour was begun. Almost every inch of the 6,800 feet of quay walls had been damaged, and only the corners were intact. The earthquake had tossed debris into the water, so that much of the area alongside was foul. In some places the walls had tumbled towards the water, and in others away from it, so that every section presented difficult problems to the builders. The earthquake did not affect the depth of water in the harbour, but much wreckage had to be removed, as a number of burning lighters and boats had caught fire while alongside wharves and, having been blown off the shore by the wind, had foundered.

The essentials of reconstruction were speed and strength; the port had to be put in order quickly but the repairs had to be made sufficiently strong to stand any further shocks. The heads of the breakwaters, including the two lighthouses, had sunk about 12 feet, and, although the parts near the land were not badly damaged, considerable lengths were shattered just where protection was most needed. As the quay walls were destroyed and ships could not get alongside, cargo had to be discharged into lighters. In bad weather the sea rolled in over the sunken and damaged breakwaters so that all work of unloading had to stop. It was clear that the first task was to reconstruct breakwaters and to repair quay walls. Newly extended parts on either side of the landing pier had escaped much damage, and temporary repairs made them fit to receive ships.

Triumph Over Disaster

Old concrete blocks from the broken quays were used to repair breakwaters and sea-

Repairs were carried out in advance of schedule. The breakwater was repaired first, then the quay walls and the barge walls, and finally the landing pier. Concrete blocks were set along the edges of the sunken break-

Huge masses of concrete, which had broken when the quay walls at one part of the harbour had collapsed, were so heavy that the cranes could not lift them. The rubble had to be removed by dipper dredgers, grab dredgers and sand pumps before the huge concrete blocks, 36 feet long, which had fallen into the harbour, could be tackled. These big masses were broken up by explosives so that the cranes could lift them. The surface of the concrete was cleaned, tins of explosive were attached to the surface at suitable places, and the charges were fired by electricity. The cement between the blocks was cut by explosives or by a rock-

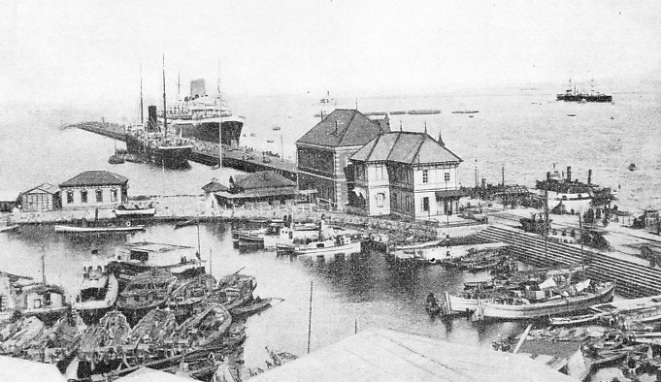

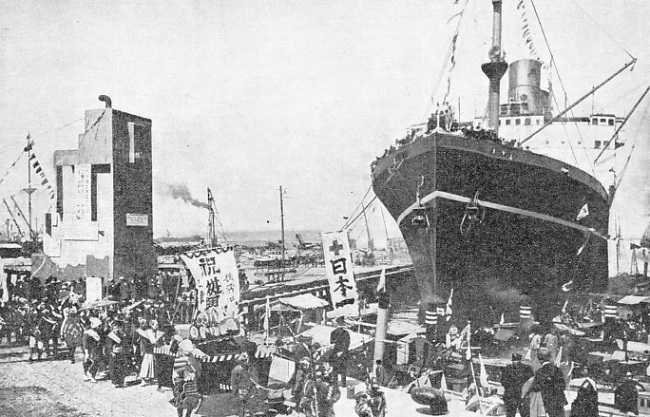

A BUSY QUAYSIDE at Yokohama. This picture shows only a small section of the great port. Harbour craft seen in the foreground carry cargo from the big ships to the shore. Some 3,000 lighters and numerous other vessels work in the harbour.

Sand and mud under the ruins were cleared so that there was space to level the foundations for the new caissons with bag-

Clearing the harbour and the basins of wreckage was in itself a great task. More than 400 sunken lighters and eighty other vessels were dredged up as well as great quantities of cargo that had sunk with them. Within two years of the earthquake reconstruction was completed, and the programme of extension, which had been interrupted by the catastrophe, was resumed.

Railway facilities are excellent, and the equipment of the port is first-

The principal imports are cotton, wheat, wool, oil, beans, fertilizers, timber and machinery; the chief exports are silk and silk piece-

Equipped as the port is with modern machinery and having been rebuilt, those who look for the glamour of the East there will see only business-

The Inland Sea

One of the best-

Outwards from the port of London the first call on this route is at Gibraltar, 1,315 miles. To Marseilles is 695 miles, after which the vessel steams 457 miles to Naples. The next call is at Port Said, 1,115 miles, the gate to the Suez Canal, Suez being over eighty miles from Port Said. The vessel steams through the Red Sea, and stops at Aden, a run of 1,310 miles, and 2,100 miles farther bring her to Colombo, Ceylon. It is another 1,280 miles to Penang, after which the ship steams 390 miles to Singapore and then 1,440 miles to Hong Kong. The distance to Shanghai is another 830 miles, and the next run of 550 miles is to Moji, the port at the western entrance to the famous Inland Sea of Japan. The width is only about four miles between Moji and Shimonoseki, which is opposite. The Inland Sea teems with fish and has played a prominent part in the story of Japan. The distance from Moji through these tranquil waters to Kobe is 240 miles.

THERE ARE BERTHS FOR SEVENTEEN SHIPS at the quays in the port of Yokohama. In the entire inner harbour there are also twenty-

Called the Seto-

Kobe -

The P. & O. line runs a fortnightly service from London by a route that is slightly different from that of the Japanese company. These liners call at Gibraltar, Marseilles, Port Said, Aden, Bombay, Colombo, Penang, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Moji and Kobe.

The Blue Funnel liners start from Liverpool and the service is monthly, via the Suez Canal and Shanghai. Other lines connecting with Europe are the Hamburg-

On the other side of the world, fast liners link Yokohama with Canada and the United States. The Canadian Pacific liner Empress of Japan holds the Blue Riband of the Pacific, and this company operates between Yokohama and Vancouver. The biggest liner on this route, the Empress of Japan, is the largest and fastest ship operating between North America and the Orient, having a gross registered tonnage of 26,000. Her sister ship is the Empress of Canada, 21,500 tons. The two liners on the direct route are the Empress of Asia, 16,900 tons, and the Empress of Russia, 16,800 tons. The distance by the direct route is 4,283 miles, and the time is ten days; the passage via Honolulu takes thirteen days. These all-

The Empress of Japan, speed 23 knots, is the flagship of the company’s Pacific fleet. She has a red and gold palm court and ball-

The Empress of Canada is noted for her long gallery, her card-

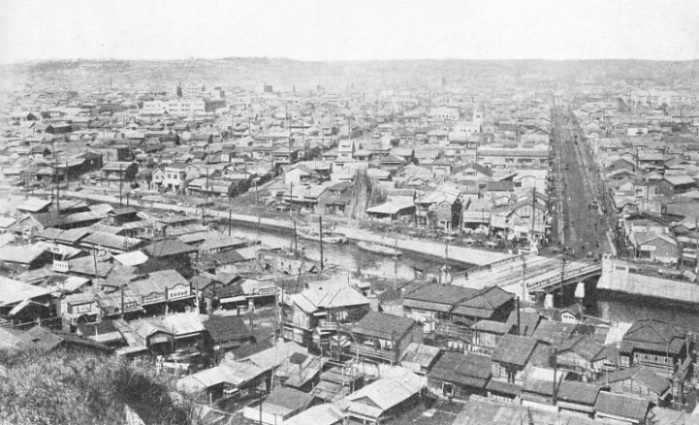

OUT OF CHARRED RUIN AND WRECKAGE rose the modern city of Yokohama, after the terrible disaster of September, 1923, when the port was devastated by fire and earthquake. It took two years for the Government and the municipal authorities to reconstruct the harbour after the earthquake. The reconstruction of the city took six years and was carried out on the American plan, and the city is now divided into five wards. The present population of Yokohama is over 709,003.

The sister ships Empress of Asia and Empress of Russia sail direct to Yokohama in ten days, Kobe in eleven, Nagasaki in twelve, Shanghai in fourteen, Hong Kong in seventeen and Manila in twenty. These vessels and the crack ships of other lines are making the Pacific the playground of western Americans, as in their luxury and speed they compare with the great Atlantic liners.

Twenty-

Another famous company which makes Yokohama a port of call is Dollar Steamship Lines, the vessels of which include two 22,000-

In addition, there are services to South America, South Africa, and to Australia, so that Yokohama is one of the most accessible ports in the world.

The city has been re-

All the other parts of the city are Japanese. The theatres and cinemas are in Isezaki-

Yokohama Park, which was laid out in the early days of the Settlement, was a place of refuge during the earthquake. A good view of the city and harbour is obtained from Nogeyama Park, the largest in the city, which is on the side of a hill. This park was made after the earthquake, and relics of the disaster are housed in the Earthquake Memorial Hall near by. A reservoir of the waterworks is in the park.

Although the Bay of Tokyo between Yokohama and the capital is shallow, the sea quickly becomes choppy in a strong wind, especially in winter, and hampers sampans, barges, and lighters heavily laden with goods to and from Tokyo, many small craft and their cargoes being damaged in bad weather. As big vessels on foreign routes cannot reach Tokyo, import and export manufacturers find Yokohama more suitable for their factories.

The road and railway facilities between Yokohama and Tokyo are excellent; fast trains cover the distance in about half an hour. There are five railway stations in the port and Yokohama Station is on the main line between Tokyo and Kobe. The fortunes of Yokohama are bound up with those of the capital, to which Yokohama is the gate.

At the time of writing the population of Tokyo is estimated at approximately 5,663,000, making it the third city in the world. As the deep-

GENERAL VIEW of Yokohama. Half of the eighteen-

You can read more on “Japanese Bulk Cargo Carrier”, “Japanese Inland Sea Passenger Ship” and “Japanese Shipping” on this website.