© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The World’s Most Famous Ship: HMS “Victory”

HMS “Victory” has played a noble part in the making of British naval history. To-

A LINE OF FAMOUS ADMIRALS, including Nelson, Hyde Parker, Kempenfelt, and Sir John Jervis (afterwards Lord St. Vincent), hoisted their flag in HMS Victory. The photograph shows the Victory before she was removed to dry dock in 1922; at various times before that date she had been in danger. Shortly after the end of the Napoleonic wars she was saved from the scrappers’ yard. Then Princess Victoria’s (afterwards Queen Victoria) personal interest in the Victory made the public realize that the ship was a national heritage. In 1908, after having been rammed by an obsolete warship, the Victory was saved from the shipbreakers by King Edward VII.

MOST of the world’s navies have contrived to retain some historic ship as an object of veneration and of inspiration to the younger generation. Of all these ships there is none to compare with Nelson’s flagship, Victory, which, restored with infinite care to her Trafalgar condition, now attracts thousands of British and foreign visitors to her berth in dock at Portsmouth Yard. Her pre-

The Victory inherited a name of magnificent tradition in the annals of the Royal Navy. The name was given to a royal ship in Tudor times, when England, by the spirit and gallantry of her seamen, was beginning to consolidate her sea-

The previous Victory, herself the finest ship of her day, had been lost with all hands. A disaster of this kind has generally debarred a name from being repeated. Happily, however, the authorities decided to override superstition and, when it was decided in 1759 to build a first-

The Victory was so big that, in the same way as several other unusually large ships, she was not built on an ordinary inclined slipway, but in dry dock at Chatham, directly under the eye of the Admiral Superintendent. This dock was roofed over for the purpose and the ship was laid down there in July, 1759.

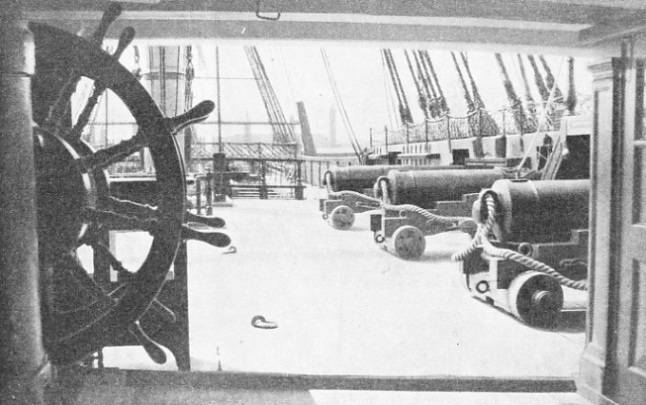

THE QUARTER DECK OF HMS VICTORY as seen from the Master’s cabin. In a modern warship the Navigating Officer holds a position similar to that of a Master in Nelson’s day. The guns on the right of this picture are three long 12-

A line-

When she was new the Victory carried thirty 42-

When the Victory was completed in the early summer of 1778, it was obvious that war with France was inevitable. She was sent round from Chatham to Portsmouth to hoist the flag of Admiral the Hon. Augustus Keppel, Commander-

The Victory underwent large repairs in 1789, but, apart from that, she was kept busy in the almost incessant fighting with France. In 1781, under Kempenfelt, she was in the partial engagement with De Guichen’s French fleet which succeeded in cutting off his convoy. But the Admiral soon afterwards transferred his flag to the Royal George and went down in her at Spithead, the Victory being close by at the time. Under Howe in 1782 she led the fleet which raised the siege of Gibraltar, and in the following year she was paid off.

The outbreak of the Revolutionary War in 1793 saw the Victory in the Mediterranean. She was first under Sir Hyde Parker and then under Lord Hood, taking part in the occupation of Toulon in collaboration with the French Royalists and in the subsequent abandon-

After many other minor actions, including Hotham’s fight off Cape Roux, she was chosen by Sir John Jervis as his flagship in 1795.

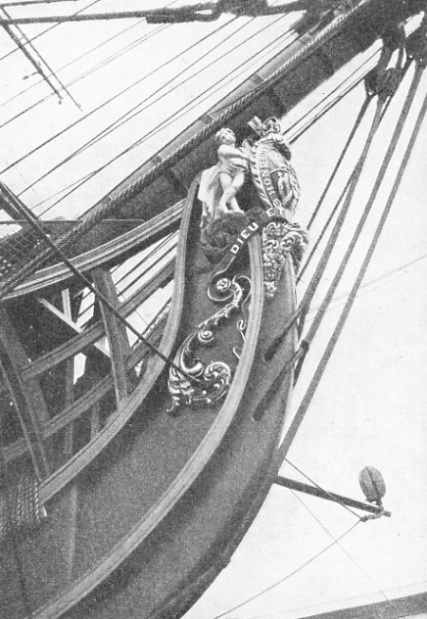

THE FIGUREHEAD on the bow of HMS Victory. This famous ship has undergone many repairs and changes, but her original dimensions were: 152¼ feet long on the keel, a beam of 52 feet, a depth of hold of 21 ft 6-

As flagship at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent her name became a household word all over England. Before the end of the year, however, she was relegated to the undignified job of prison hospital ship in the Medway, within sight of the dockyard at which she had been built. After a spell of this work, when she was undoubtedly showing the results of her hard service, she was again put into dockyard bands to undergo a refit that might be described as a reconstruction. The original stern, covered with open galleries, was replaced by a much simpler flush stern with glass windows. At the same time the elaborate figurehead with which she had been built was replaced with an unpretentious crowned shield containing the Royal Arms and supported by cupids.

This work prevented her from taking part in some of the hard-

When she was ready for sea again in 1803, in condition as good as new without having lost her remarkable sailing qualities, the Victory was chosen by Nelson to be his flagship on his appointment to be Commander-

While Nelson had the greater part of his fleet refitting as well as it could in an open anchorage between Sardinia and Corsica he heard that the Toulon fleet had slipped out and had disappeared. Concluding that Admiral Villeneuve would make for the Eastern Mediterranean, Nelson took his ships to Alexandria and back, only to find that the French had been forced to return to Toulon by stress of weather. By that time his own ships were feeling the strain and he had to draw them off again for urgent repairs.

Villeneuve took the opportunity to slip out again, making his way to the West Indies to collect every available French ship for the invasion campaign. Nelson followed him, leading the fleet in the Victory, but he was misled by false information from the Army, and the French fleet escaped contact. Nelson made his way back to Europe, the British fleet going to Spithead to refresh. When news was received that Villeneuve was in Cadiz with a fine Franco-

The allied fleet duly came out and attempted to get through the Straits of Gibraltar to Toulon, with the combined fleet of Nelson and Collingwood after it.

THE PORT HAMMOCK NETTINGS, in which the seamen stowed their hammocks. This kept their quarters clear and protected the men from shot and flying splinters.

The Battle of Trafalgar which followed on October 21, 1805, is too well known to demand a description in this chapter; but, as might have been expected, the Victory took her full part in it. She flew Nelson’s flag at the head of one line, while Collingwood led the other. The famous signal “England expects that every man will do his duty” was made as the two fleets closed, immediately followed by his favourite “Engage the enemy more closely” long before she had arrived within range. Captain Blackwood attempted to persuade Nelson to go to his ship the Euryalus, out of the line of battle, and to conduct the action from a position in which he could see the two parts of the force and at the same time be comparatively safe. But Nelson would not agree and, in a light wind, continued to lead the fleet slowly forward in the Victory. For a long time she was under the fire of the French broadsides before she could bring a gun to bear, and she suffered severely. There was a poor breeze, and the Victory’s already slow speed was slackened by her mizen topmast being brought down by French gunfire. When she was finally alongside the enemy ships she gave just as much as she received. The sixty-

To many people the Battle of Trafalgar marked the end of the Victory’s active service career, but she was to do a good deal of work after that. Given some sort of a jury rig at Gibraltar, she was sent home, and in January, 1806, was paid off. In those days this meant the discharge of the whole ship’s company, which Nelson had brought to such perfection. Thoroughly refitted, the Victory was ready for active service again in the spring of 1808, and for the next five years she was fully occupied.

“Save the ‘Victory’!”

She was prominent when Sir John Moore’s army was withdrawn from Corunna. Later she became the flagship of Admiral Sir James Saumarez, Nelson’s old companion. Under him she did much work in the Baltic, including the blockade of Cronstadt.

In 1814 she underwent a further thorough refit, even more of a reconstruction than before. The following year she was again available as a flagship, when six Admirals claimed the honour of flying their flag in her. The end of the Napoleonic wars ended this dispute. Soon afterwards it was suggested that she was past service and should be sold to scrappers on Thames-

In spite of her reconstruction and the care which was latterly given to her, she was suffering the effects of her great age, and in 1922 the public was shocked to learn that her fabric was in a bad state and that she was in danger of falling to pieces. A “Save the Victory Fund” was started and, largely because of the generosity of Sir James Caird, a patriotic shipowner, the necessary sum was raised to reconstruct her completely. The opportunity was taken to restore her appearance to that of her proudest days. She was put in an iron cradle and, encased in cement, is now carefully preserved in a dry dock in Portsmouth Dockyard.

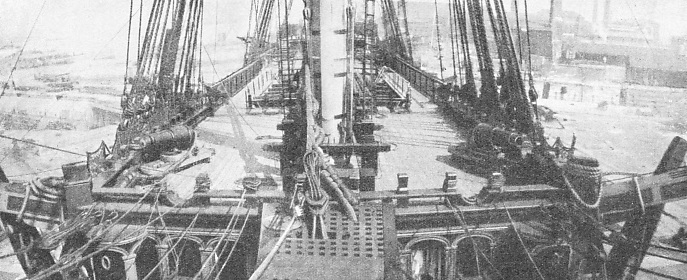

A VIEW TAKEN FROM THE BOWSPRIT HEAD showing the full width of the forecastle and the two 68-

An impression of HMS Victory by Frank H Mason. In 1922 the fabric of this famous ship was in danger of falling to pieces. An appeal was started and, largely because of the generosity of Sir James Caird, the well-

You can read more on “Battle of the Nile”, “Battle of Trafalgar” and “The Navy Goes to Work” on this website.