© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

R.M.M.V. “Stirling Castle”

A new record in the history of the South African mail service was established on September 4, 1936, when the motorship “Stirling Castle” broke the existing Southampton to Capetown speed record by more than thirty-

A TWIN-

THE world’s largest ships have a significance far beyond that due to their mighty engines and impressive bulk. Thousands of tons, driven hundreds of miles a day, to destinations on the other side of the world -

A great liner is the largest self-

Consider for example the Stirling Castle. At 4 pm on a Friday afternoon she lies alongside the quay at Southampton. As the clock strikes the hour the last gangway is withdrawn, the last hawser is let go, the water churns beneath the stern as the screws revolve -

A fortnight later the beautiful great vessel enters the harbour at Capetown, 6,000 miles away. Throughout that long voyage her little world of inhabitants has been housed and fed in the utmost comfort. They have been sheltered, warmed against the cold or fanned in the heat; they have been entertained and provided with all the amenities of a well-

While sleeping in comfortable beds, walking on broad and sheltered decks, or lounging in luxurious rooms, they have been carried thousands of miles with such speed and efficiency that many of them will not realize that their punctual arrival in South Africa represents a modern miracle of transport.

The great liner lies alongside in Capetown for about a day and then heads out to sea again to complete her voyage. A few days later, after calls at Port Elizabeth and East London, she noses past the Bluff at Durban, having rounded Africa’s southernmost extremity and traversed 800 miles or so of the Indian Ocean.

Nine days later she will slip quietly out to sea again, bound for England with passengers, mail and cargo. One of the world’s great ships, she moves without fuss on her lawful occasions; and later only a line in the newspapers -

Not many will pause to consider what manifold applications of science have contributed to the feat so tersely recorded. Fewer still will reflect on the unremitting effort required to run a regular service of mail vessels, forming a continuous bond between the countries concerned.

The Stirling Castle is but one link in the endless chain of communications joining Great Britain with South Africa. As the one vessel arrives at Southampton a sister ship will be arriving at Capetown, and other vessels on the service will ply between British and South African ports, “swift shuttles of an Empire’s loom, that weave us main to main”. We can appreciate the significance of the one vessel’s performance only if we visualize her as a unit in such a service.

The Stirling Castle is a fast new twin-

Launched at Belfast in 1935 by Harland and Wolff, the Stirling Castle has a gross tonnage of 25,550. She measures 680 feet between perpendiculars, 725 feet overall, and has a breadth of 82 feet. Her curved stem and cruiser stern, her two masts and streamlined red funnel with a black top, and her attractive lavender-

Structurally she has the fundamental simplicity of a great work of art. There are four complete steel decks, and spacious Promenade and Boat Decks, as well as Orlop and Lower Orlop Decks. There are three cargo holds forward and four cargo holds aft, with corresponding cargo ’tween decks.

Ordinary cargo is carried in Nos. 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7 Lower Holds. The remaining holds and ’tween decks are insulated and arranged for the carriage of deciduous and citrous fruits, in which there is a large trade from South Africa.

Some of the compartments are arranged for chilled and frozen produce. Altogether a total insulated capacity of about 330,000 cubic feet is provided.

The Stirling Castle is divided into twelve watertight compartments by eleven massive bulkheads, all of which extend to C Deck. Under the holds is the continuous double bottom -

The deep fresh-

The arrangements for cargo are interesting. Considerable loads are carried, and must be handled with all the expedition demanded of a vessel which flies the pendant showing that she carries the Royal Mails. The cargo hatches to the seven holds are served by fifteen tubular steel derricks, including two of the 12-

The derricks are worked by sixteen electric winches, those at No. 2 Hatch being of special heavy-

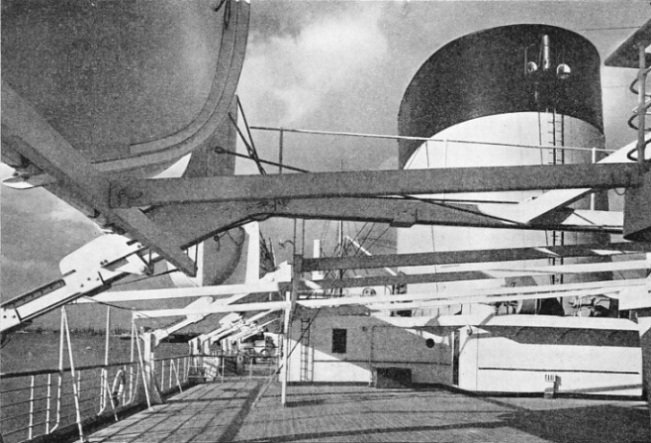

THE SPACIOUS BOAT DECK of the Stirling Castle is dominated by the brightly-

For protection against fire the cargo spaces are equipped with a fire detection and extinguishing system; and throughout the accommodation there are a sprinkler extinguishing system and “firefoam” extinguishers. Fire-

The heart of the ship, beating rhythmically and powerfully from port to port, is the engine-

Some idea of the importance and complexity of the work in the main and auxiliary engine-

To supply the continual heavy demands for electricity a generous reserve of power is provided by an installation of five diesel generator sets. Each set is capable of delivering 700 kilowatts at an easy rating.

Perfectly Controlled Power

The complete power station thus compressed into the engine-

At the starting-

In sharp contrast to the dark-

In the cabin-

Throughout the public rooms and in all passengers’ and crews’ quarters electric heating is installed. The powerful ventilation system ensures that in the hottest weather every part of the vessel is kept comfortably cool. In the cabins the electrically-

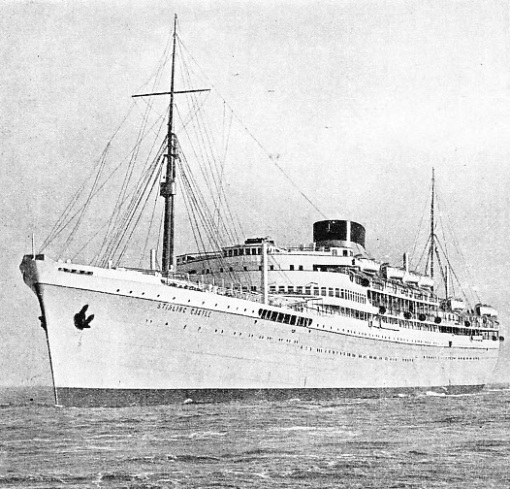

THE ATTRACTIVE COLOURING of the Union Castle liner Stirling Castle, 25,550 tons gross, adds much to her striking modern appearance. Her hull is painted lavender-

The Stirling Castle was the first ocean liner in which the Harlandic clock control system was installed. This system keeps correct ship’s time during the whole voyage, thus obviating the necessity for putting the clocks forward or back at a certain time daily to conform with the ship’s movements east or west of the Greenwich meridian. The hands of the clocks move continuously instead of in half-

Another interesting instance of the elimination of noise is provided by the luminous system of communication with the stewards’ department. Outside the door of each stateroom are two small electric lamps, one red for summoning a steward and the other green for summoning a stewardess.

Inside the room are installed pushes of corresponding colours. The operation of a push lights the appropriate lamp outside the cabin and in various parts of the vessel to show that the services of a steward or stewardess are required. The lamp remains burning until the attendant reaches the door of the cabin and operates another control push there. Silent and efficient service is thus ensured.

The public rooms of the Stirling Castle have dignity and spaciousness. Choice South African woods are appropriately used, and the latest forms of electric lighting have been embodied with pronounced success. In the public rooms all the lighting is indirect, the Stirling Castle having been one of the first British vessels to adopt, this feature.

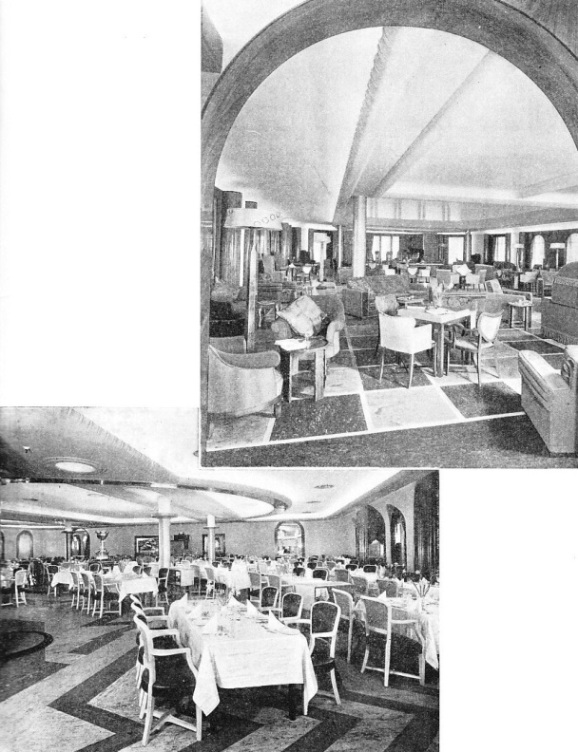

INDIRECT LIGHTING is one of the main features of the public accommodation in the Stirling Castle. One effect is to enhance spaciousness, as shown by this photograph of a portion of the first-

ELEGANCE AND COMFORT are keynotes of the interior decoration of the Stirling Castle. The first-

Of the public rooms in the Stirling Castle, pride of place goes to the first-

Other public rooms in the first-

Cabin-

While the passengers, in these attractive surroundings, engage in the varied activities of a long voyage, the work of the ship must go on almost unnoticed.

Below, the engineering department continually watches all the multifarious machinery in its charge. On the bridge the navigating officers keep their control and ceaseless check on the vessel’s course. In the wireless room messages are continually coming and going, for the ship is never out of touch with other vessels or the land.

A hive of specialized and co-

In the previous year the founder of the Castle Line -

The first of these vessels were the Stirling Castle, Tantallon Castle, Carnarvon Castle and Kenilworth Castle. The leading dimensions of the Stirling Castle, which was of 1,165 tons, were length 200 ft 7-

After about ten years experience in the Calcutta trade, Mr. Currie decided to substitute steamers for the sailing vessels. He built the steamers Edinburgh Castle, Windsor Castle, Walmer Castle and Dover Castle.

Half a Century of Progress

While these steamers were under consideration Mr. Currie altered his intentions as to their future employment and decided to run them in the South African trade. Until the Castle packets were completed and equipped he placed the steamers Iceland and Gothland in the service between Southampton and the Cape. Starting her first voyage on January 23, 1872, the Iceland was the pioneer steamer of the Castle Line.

The Castle Line received an allowance from the Cape Parliament tor the carriage of letters, and when the postal contract was renewed in 1876 the mail service was equally divided between the Union and the Castle Lines.

The Union Line was the elder, having been formed in 1853 under the title Union Steam Collier Company. Thus the two important fleets which in 1900 became the Union-

The Union Steam Collier Company began modestly with a fleet of small steamers -

Leaving Southampton on August 21, and arriving at Capetown on September 4, she made a record passage of 13 days 6 hours 30 minutes, including a stop of three hours at Madeira, at an average speed of 18.9 knots.

The Stirling Castle, thus taking her honourable place in the history of the maritime mail service to South Africa, represents not finality, but the spirit of progress which ever urges man forward.

H er speed, her size, her power and every detail of her design make it impossible to compare her with the Stirling Castle of 1863. Every detail is different, save two. On her bows she bears the same proud name, Stirling Castle. And she is driven by the same force -

er speed, her size, her power and every detail of her design make it impossible to compare her with the Stirling Castle of 1863. Every detail is different, save two. On her bows she bears the same proud name, Stirling Castle. And she is driven by the same force -

ONE OF THE LARGEST MOTOR. SHIPS IN THE WORLD, and at the time of her building, the largest vessel in the South African service, the Union-

You can read more on “British Shipping”, “Durban: South Africa’s Eastern Port” and “RMS Orion” on this website.