© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Marine Measurements

Ships are so immense that comparisons are difficult except on certain common measurements. The principles on which the various tonnages and other standards of capacity or water displacement are based are clearly outlined in this review of the subject

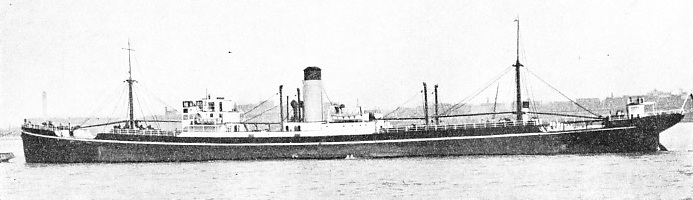

THE LOAD DRAUGHT of a ship is her depth in the water when she is fully loaded with fuel, cargo, water, stores and the like. The Trepca, above, is down to her load water-

TONNAGE forms the basis of comparison between all ships except the smallest yachts and launches. It is a term that involves a considerable amount of complication.

Gross tonnage is an artificial standard of measurement and has nothing whatever to do with the weight of a ship or her displacement of water. It is arrived at by measuring the total volume of enclosed spaces in the ship. This measurement is carried out under the regulations of the Board of Trade and the provisions of the Merchant Shipping Act.

The volume is measured, in cubic feet, and is divided by 100. The resultant figure gives the gross tonnage. The reason for making this calculation is that the enclosed spaces are deemed to be filled with a “standard” cargo weighing one ton for every 100 cubic feet of its volume. In practice, an average cargo weighs one ton for 42 cubic feet.

From the gross tonnage is deducted a proportion representing the spaces in the ship that do not earn revenue by carrying passengers or cargo but are necessary for propulsion, navigation, certain stores and the provision of living quarters for her personnel. The figure thus arrived at is known as the net tonnage and is cut into the Main Beam of the ship, with her official number in the register of British ships.

It is on the net tonnage that port and other dues are payable, and this fact has had a material influence on the design of ships. Shelter decks, for instance, are technically open to the sea by “tonnage openings” that can be closed by wooden hatch covers. The spaces below these openings may be exempt from inclusion in computing the tonnage.

Yachts are always measured by Thames Measurement Tonnage, on the same principle as. that used in computing gross tonnage, but dimensions only are taken, not volume, and the result is divided by 94.

To illustrate the vagaries of national measurement in computing tonnage, the re-

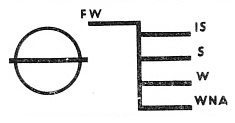

STATUTORY MARKS carried by a vessel -

This measurement principle is not ideal and is used for merchant ships only in default of something better. Warships whose weight does not vary with the cargo that they are carrying, as does that of merchant vessels, can use the more logical displacement tonnage.

Here is involved one of the oldest physical laws known to science -

The application of the principle is of immense importance to shipping. It enables the weight of certain types of ships to be calculated, and by the use of suitable markings on the hull the differences in the weight of the cargo can be determined at any stage of its loading or unloading.

Let us assume that the volume, or bulk, of a ship’s hull below the waterline, as calculated from the drawings of her builders, is 3,500 cubic feet. We know that 35 cubic feet of sea water weigh one ton. Therefore to ascertain the ship's weight, for displacement, we divide the above figure of 3,500 by 35, giving 100 as the displacement tonnage.

The method of determining the weight of cargo in a merchant vessel is particularly interesting. Above are illustrated the statutory markings, on the side of a ship’s hull, denoting the load water-

To facilitate the use of these draught marks, the staff of the shipbuilder’s drawing office prepares a displacement scale from the ship’s drawings, showing the weight of the vessel and cargo at successive levels or water-

DRAUGHT MARKS, cut into the steel at stem and stern, show, in feet, the draught of a ship at any given time. Thus the loading of a ship can be checked fore and aft and the approximate weight of cargo calculated. Here are the stern draught marks of the Berengaria, 52,101 tons gross, photographed when her rudder was being refitted at Southampton after it had been repaired at Darlington.

When a ship has been completed, and before any stores or fuel are loaded, the draught is noted by the numbered marks at bow and stern and allowances are made for the water ballast. The mean reading is then compared with the scale and the displacement, and the weight of the ship and machinery is noted. This weight is known as the lightweight, and the added weight, up to the maximum of the Plimsoll mark, is called the deadweight.

Steamers are always referred to in chartering business as being of so many tons deadweight. For instance, a 10,000-

The complication of ship measurement does not end with the tonnage. Length, beam and depth (always given in that order) are all subject to certain qualifications when used as a basis of comparison between vessels. The length of a ship between perpendiculars, is the measurement taken from a presumed vertical line where the stem cuts the load water line, to another line passing vertically to the after side of the stern post on which the rudder is hinged.

When there is no stern post and the rudder is otherwise supported, the after perpendicular is taken from the fore side of the rudder stock. The above measurement is classified as a “registered” dimension, but under another system of measuring -

water-

The moulded depth of a ship is measured from the top of a specified deck beam, at the side, at the middle of the water-

The “overall length” of a ship always exceeds the moulded or registered length, because it is measured from the foremost part of the stem (but ex-

Draught is a term that has a variety of uses in defining the dimensions of a ship. Usually draught is the maximum distance of the lowest point of the keel below the water-

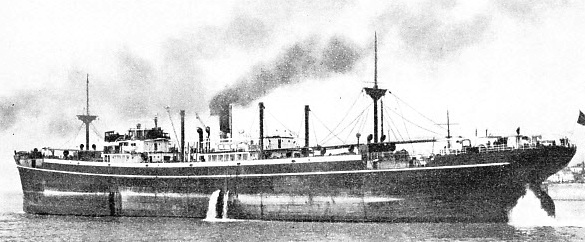

IN BALLAST. When a ship has no cargo on board her ballast tanks must be filled to enable her to be handled at sea. In this condition she is described as in ballast and the propeller is often partly visible. The Avala is shown thus, high in the water. Of 6,403 tons gross, she is a Jugoslavenski Lloyd vessel with a length of 425 feet, a beam of 58 ft 3-

You can read more on “Building a Liner”, “How the Modern Ship is Tested” and “Ship Type & Deck Arrangement” on this website.