© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Record-Breaker “Lightning”

Designed and built in the United States of America for English owners, the Lightning was one of the most famous of the racing clippers

FOR a variety of reasons particular interest centres round the four big extreme clipper ships which Donald Mackay, the great Scottish-

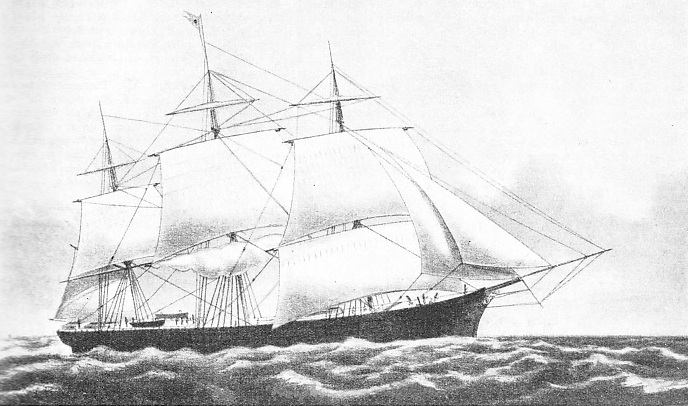

GRACEFULLY RIDING THE SEAS. For may years the Lightning’s career, after her maiden voyage from Liverpool to Melbourne in 1854, was a record of fast passages. The Lightning had two complete decks and a poop. The ‘tween deck, designed for the transport of emigrants, was unusually spacious. She had four big state rooms, whose furnishing and comfort were then unparalleled, and accommodation for second-

The discovery of gold in California in 1849 gave the first great chance to the extreme American clippers. They carried the adventurous gold-

The British builders soon learned to turn out ships as good as the Americans, but there had been no time for this influence to be felt when gold was discovered in Australia in 1850. News travelled slowly in those days, and first reports were always suspect. It was not until the following year that the adventurous Briton learned that he had just the same chance of immense profit under the Union Jack as he had under the Stars and Stripes. Passenger accommodation to Australia, no matter how rough and uncomfort-

James Baines was one of the first shipowners to take advantage of the rush. He was a young man, the son of a widow who was content to keep a small sweet-

The profits of Baines’s enterprise and the reputation that he made with his early ships soon put him into a position to order new tonnage of the finest type on the market. By then the China clipper had been developed into a magnificent little vessel; but she was designed entirely for the tea trade and possessed many features which, in Baines’s shrewd opinion, did not fit her too well for the Australian trade as it then existed. He wanted something more resembling the extreme clippers that the shipyards of New England were building for the Californian trade.

Eclipsing China Clippers

These were bigger ships than the China clippers, and had fine hulls that were still sufficiently spacious -

The Lightning was the first vessel to be designed and built in the United States for English owners since the War of Independence. It may be taken for granted that a man with as much pride in his work as Donald Mackay would be spurred to his greatest efforts by this fact. The Lightning’s dimensions were 244 feet overall by a beam of 44 by 23 feet depth of hold, giving her a registered tonnage of 1,468 by what was then called the “new British measurement”. This is still in force.

The New England States were then producing magnificent shipbuilding timber, and Mackay chose the best. All the knees in the hold, hooks and pointers were of selected white oak, well seasoned, the knees in the ’tween decks were hackmatack (American larch). Hard pine was used for the scantlings and for the lower deck; the upper deck was of white pine. Iron and copper bolts were used for the fastenings, of 1-

The fore lowermast was 86 ft long by 37-

The Lightning had two complete decks and a poop, the poop being later extended forward to give better accommodation by linking up with the big midship house and the topgallant forecastle. The ’tween decks, designed principally for the carriage of emigrants, had a head-

On the Australian run a fast ship could always reckon on doubling her crew for the outward journey by permitting men to work their passage to the goldfields. The crew was housed in a big topgallant forecastle extending to the fore rigging. An innovation was the provision of three gangways connecting this forecastle with the midship house and with the poop, so that the men could pass from end to end of the ship at their work without having to go down into the waist. This was constantly under water, because of the ship’s lines and the way she was driven.

Over the wheel a relatively big house was built, partly to give protection to the helmsman when she was running her easting down, partly to provide a smoke room -

On either side of the ’tween decks, which were fitted for the steerage passengers, there were ten plate-

When the Lightning arrived at Liverpool her lines were greatly admired. She was declared to be one of the smartest ships known, with the most daringly hollow bow ever conceived. James Baines carried out a number of improvements in the accommodation and, after a short experience, the rig was slightly altered. Instead of being a three-

Day’s Run of 436 Miles

Captain “Bully” Forbes, who had made such a name in the Marco Polo, was appointed to the command of the Lightning. He superintended the final touches in Mackay’s yard at East Boston; and when she was ready for sea she was loaded for Enoch Train’s clipper line to Liverpool. Captain Lauchlan McKay, the younger brother of her builder and himself a clipper ship master with a high reputation, accompanied Forbes on the run across the Atlantic. As the Red Jacket, built for Pilkington and Wilson’s rival White Star Line to Australia, was booked to sail from New York on the day after the Lightning was due to leave Boston, everybody was anxious that the Lightning should do her best. She certainly did, for the run from Boston Light to Liverpool was made in thirteen days nineteen and a half hours, her best day’s run being 436 miles -

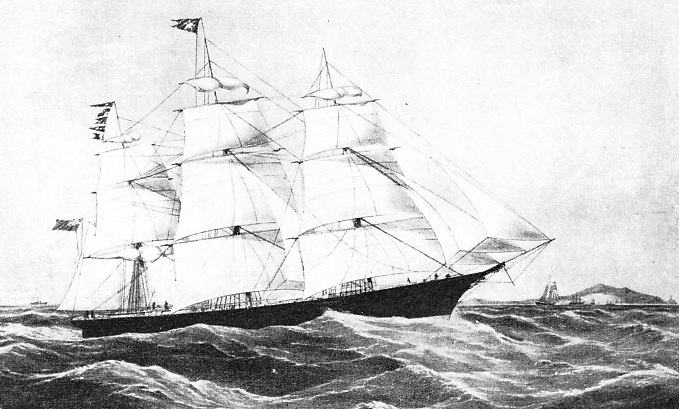

The Red Jacket did the run from Sandy Hook to Liverpool in thirteen days one hour, with a best day’s run of 413 miles, so that both ships started with a preliminary advertisement that was worth much on the Australian trade. But even James Baines lost his nerve when he saw the Lightning’s hollow bow lines. He had them filled in to a certain extent with slabs of oak, much to the disgust of the Americans. Mackay was right, however, for when one of these slabs washed away, the other was removed, and she was certainly the better ship for their loss.

In May, 1854, the Lightning left Liverpool on her maiden voyage to Melbourne with a good crowd of passengers. “Bully” Forbes had as mate “Bully” Bragg, who was nearly as notorious as his captain. The voyage out was made in seventy-

THE LIGHTNING was ordered in 1853 by James Baines for the Black Ball Line from Donald Mackay, the great Scottish-

The Lightning made the homeward run in sixty-

“Bully” Forbes then left her for the Schomberg, which he was to wreck on her maiden voyage with his own career. He was succeeded by Captain Enright, one of the finest master mariners on the Australian trade. A Scandinavian by extraction, he was in many ways the direct opposite of Forbes. He had no belief in bad language or manhandling a crew. Boasting was foreign to his nature. He conducted Divine Service, to which he welcomed his forecastle hands as well as the passengers; he ran his ship with strict decorum and encouraged such amusements as the publication of a really excellent little ship’s paper, copies of which are now rare and keenly sought by collectors. Under Captain Enright the Lightning sailed from Liverpool in January, 1855, with over 700 passengers. Another good passage, with a best day’s run of 390 miles, increased her reputation in Australia, and she left for Liverpool with a few passengers and over 69,000 ounces of gold. Her passage to Queenstown wras sixty-

After that the Lightning’s career for some years was almost a catalogue of fast passages. Outward-

To India in Eighty-

In 1857 there was a break in the career of the Lightning; for the position in India was critical and troops were being hurried out by any means to hand to suppress the Mutiny. Steamers that could carry sufficient coal to cover the long steaming distance were not common. It was necessary to fall back on the auxiliaries which had been built for certain long-

stores and ammunition in the Thames, where she was thrown open to public inspection. She was greatly admired.

Captain Byrne now took over the Lightning. The new captain probably did as well as his distinguished predecessor could have done, for the Lightning made the passage from Portsmouth to the Sand Heads -

This famous ship then returned to the regular Liverpool-

In 1866 the Lightning, with the Champion of the Seas, was sold to Thomas Harrison of Liverpool. In October, 1869, while the Lightning was loading wool at Geelong (Victoria), her cargo caught fire and she had to be sunk.

A RIVAL IN SPEED to the famous Lightning was the Red Jacket. This ship -

You can read more on “Handling the Sailing Ship”, “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle” and “Romance of the Racing Clippers” on this website.