© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Hull and Grimsby

On the banks of the River Humber are situated the ports of Hull and Grimsby, famous for their importance in commercial shipping and particularly in the fishing industry. Grimsby claims to be the world’s largest fishing port

THE PORT OF HULL has two distinct features in relation to shipping. At Hull there is an extensive cargo and passenger trade, and the port has also an important connexion with the fishing industry. As at the sister port of Grimsby, on the southern bank of the River Humber, quays and docks at Hull are crowded with steam trawlers and other fishing craft.

ON the River Humber are two remarkable ports — Hull on the Yorkshire and Grimsby on the Lincolnshire shore. They are remarkable because they are the two biggest fishing ports in the world and because Hull is one of the largest ports of Great Britain.

Apart from a vast quantity of worldwide shipping which moves upon the “yellow” Humber, there is no other waterway that offers the same spectacle of the ceaseless coming and going of steam trawlers. To and from the North Sea, the White Sea, Greenland, Iceland and high latitudes generally these unrivalled craft go in procession. Connected with them at the two ports are docks, markets and organizations which are marvels of energy and efficiency.

Hull and Grimsby offer striking contrasts. Hull, officially known as Kingston-

Hull has an atmosphere of fascination, for in the heart of its fine public buildings the visitor suddenly comes across docks and ships, and he is in touch with all the globe. There are two maritime worlds in the city — that of commercial and passenger shipping and that of the fishing industry. The two are quite separate, and, although the link with the liner and the cargo steamer is always present, the fishing quarter may be missed unless it is specially looked for. But not to see it is to fail to understand what Hull really represents.

Grimsby is a totally different place. Not even its dearest friend could call it beautiful; indeed it is depressingly ugly, but it makes up in success what it lacks in natural attraction. It would be hard to find a port which owes more to foresight, unyielding resolution and constant work than Grimsby. Well within living memory there were great and apparently hopeless areas which are now covered with docks and business places, and not only yield big revenues but also have an important place in the food supply of the nation.

Grimsby, with 92,500 inhabitants [in 1936], is the largest town in Lincolnshire and still claims to be the greatest fishing port in the world, a claim that is challenged by Hull. Such rivalry between these towns, so far from doing ill, is an incentive to either side to maintain the strife for mastery.

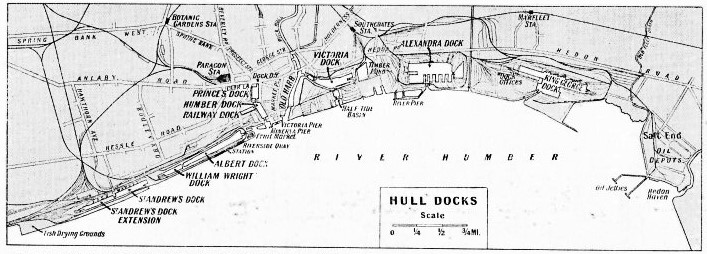

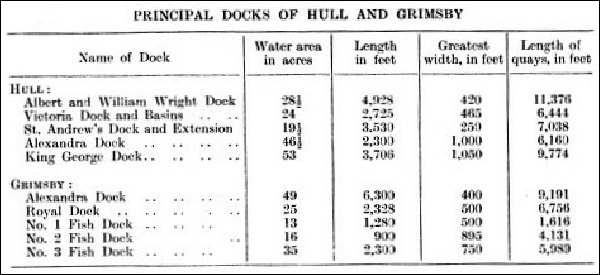

Hull docks number ten and the sole owners are the London and North Eastern Railway Company, whose immense resources have been and are still devoted to keeping the docks in the highest state of efficiency. The old North Eastern Railway Company, which is now part of the L.N.E.R. system, acquired the property of the Hull Dock Company in 1893. The docks cover a total water area of about 200 acres, with some 600 acres of open storage space. There are twelve miles of quays and a river frontage of more than seven miles. Huge warehouses for the storage of wool, grain, seed and general goods meet the eye at every turn. All the quays have rail connexion and most of them have transit sheds.

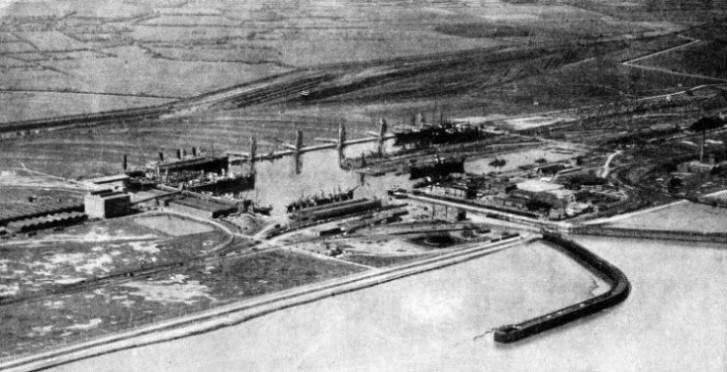

IMMINGHAM DOCK is situated a short distance upstream from Grimsby. The dock has a water area of 45 acres, and its quays extend to a length of 5,956 feet. In the basin the depth of water ranges from 23 ft. 2 in. to 47 ft. 11 in. The entrance lock is 843 feet long and 93 feet wide. On either side of the entrance a jetty has been built out into the River Humber. The Eastern Jetty is used by cruising liners, and the Western Jetty for the shipment of bunker and cargo coal.

Hull is closely linked with one of the greatest of the world’s industrial areas — the manufacturing districts of Yorkshire, Lancashire and the Midlands. Nearly 12,000,000 people live within the area which Hull claims as peculiarly its own for shipping and other business purposes. The claim is sound when we consider the exports of coal, textile goods, iron, steel, oilcloth, rubber, paints, chemicals, manures and almost numberless manufactured articles. Enormous quantities of coal are shipped from the coal-

Among the imports are wool, timber, fruit, frozen meat, grain, seeds, provisions, oil, metals, motor spirit and all kinds of wines, spirits and other dutiable goods.

Hull’s impressive trade has been built up by the dock and railway undertakings, with the zealous support of shipowners, merchants, shippers and manufacturers. Before the war of 1914-

A fleet of large ocean-

Famous for 600 Years

Famous in association with the port is the name of Thomas Wilson. The line bearing that name was at one time the largest private shipping company in the world. In 1910 the Wilson Line had a fleet of seventy-

To-

In the old days Hull was an important whaling port and many a strong ship went from, the Humber to hunt the leviathan. About 300 years ago eight whalers in Greenland went off in a shallop to hunt deer for provisions. Bad weather drove their ship to sea and, despite their efforts, they failed to rejoin her. For nine months these men endured the greatest hardships, but they managed to survive and always hoped for deliverance. For three months they lived only on the fritters or greaves — scraps of tallow — of the whale. Finally the men were found by some Hull men, who had heard of their plight.

Recently the whaling has been maintained by the factory ships. These vessels have acted as parents to smaller craft which have done extensive line fishing and transferred their catches to the big ships to be kept in refrigerators during the fishing season and then brought to England to be sold. In this way immense quantities of fish, especially halibut, have been put on the market. This particular form of fishing was one of those ventures which show the enterprising spirit of Hull. Such a system is costly and complicated and must necessarily be largely in the nature of an experiment.

Hull was the headquarters of the fleeters or “boxers” which worked the North Sea grounds throughout the year until the beginning of 1936, when the fleeting system collapsed through economic stress and all the Hullmen, in the same, way as the Grimsbymen, became single-

Hull’s antiquity as a port is shown by the fact that six centuries ago, during the Hundred Years War, Hull fitted out for service in the French wars sixteen ships, with 461 seamen. That achievement compared favourably with that of London, which supplied twenty-

The oldest docks are in the centre of the city — the “Town Docks” — and from these we advance to King George Dock, which has the largest enclosed water area on the north-

At the western extremity of the dock estate is St. Andrew’s Dock, with a water area of nearly 20 acres, including the dock extension. This dock is devoted solely to the fishing industry, and its importance is indicated by the fact that the dock supports nearly one-

Each dock has its own characteristic. Albert and William Wright Dock, for example, with a water area of 28½ acres, has double-

Near this dock is the Riverside Quay, 2,500 feet long and from 85 to 150 feet wide, which provides special facilities for passenger, fruit and provision traffic. The quay is one of the most important features of the Hull dock system, for vessels can use it at all stages of the tide. To any lover of the

estuary and the life of a great port there is endless charm in this quay and its neighbourhood. Not the least attractive feature is the ferry service which is such an important link between Hull and Grimsby.

Victoria Dock, built as long ago as in 1850, is still a fine dock, with a total water area, including basins, of 24 acres. Coal and timber are dealt with on a great scale at this dock, which is surrounded by extensive timber grounds. Hull and Grimsby are noteworthy for the extent of the timber trade. The steamer of to-

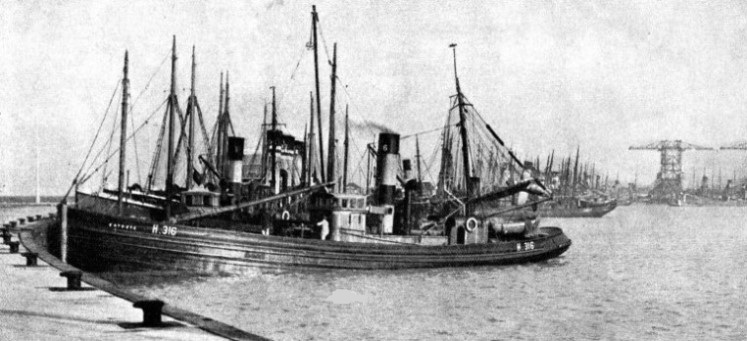

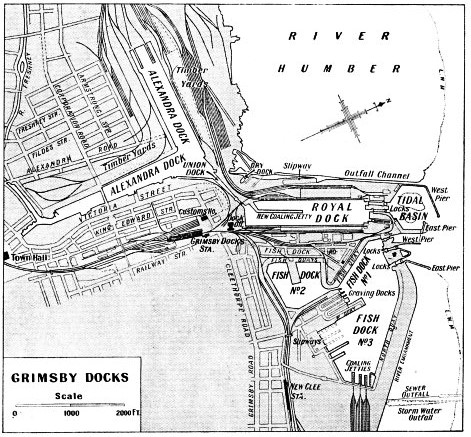

A LARGE FLEET OF DRIFTERS, steam trawlers and motor vessels supplies the requirements of the fish market at Grimsby and Hull. The development of Grimsby coincided with the growth of the fishing industry. The three fish docks at Grimsby have a combined water area of 64 acres, and the new Fish Dock was built at a cost of £1,700,000. There are two other docks, with water areas of 49 and 25 acres respectively.

Alexandra Dock, of 46½ acres, without its extension (7 acres), has 6,160 feet of quays. Its size and depth enable it to accommodate the big steamers that go to distant lands. In addition to the facilities of Alexandra Dock there is a river pier which can be used by vessels of moderate size at all stages of the tide, and it is regularly used for the handling of coal and general cargoes.

A notable feature of King George Dock is that the whole site except about 20 acres was reclaimed from the foreshore, which was formerly flooded at high water. The total area of the reclaimed land is 206 acres. The dock has a water area of nearly 53 acres and provision has been made for extension to 85 acres.

Wool and oil loom large in the trade of Hull. Extensive imports are handled at King George and Alexandra Docks and all the sheds are fitted with the most modern electric machinery to ensure quick work. The Humber is most conveniently situated in relation to the heavy woollen districts, and transit by road or by rail is rapid.

For importing oil in bulk the L.N.E.R. has made two deep-

Finally, it may be said of Hull that it is the largest centre of the vegetable oil trade in the country, and has cold storage capacity for 300,000 carcasses. The way to Grimsby lies across the broad ferry to New Holland and thence by way of the interesting port of Immingham. At Grimsby we are in another world. Reclamation has done much for Grimsby, and the indomitable spirit of her sturdy people has done more.

The chief link between the two ports is the colossal fishing industry. Fish dominates Grimsby, just as her famous hydraulic tower, 306 feet high, is the landmark of the Humber. In Grimsby you are always with the fish; in the estuary the tower cannot be missed.

Grimsby is old in foundation, young in development. Nearly ninety years ago the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (later Great Central Railway and now part of the L.N.E.R.) acquired a controlling interest in the port, and this led to the opening of the Royal Dock in 1852. Two years later No. 1 Fish Dock was built, and this was followed in 1878 by No. 2 Fish Dock. Both docks were extended as the fishing industry grew in such an astonishing manner. These docks were the forerunners of the new Fish Dock, which was begun in 1930. There are also the Alexandra Dock and the connecting Union Dock.

From small beginnings Grimsby has become the biggest of the world’s fishing ports, and a busy general port. The dock system extends to nearly 140 acres of deep water, with 450 acres of land adjoining the quay sides. The quays alone extend to more than 27,000 feet. The docks are provided with a special high-

Until recent years most of the fishing vessels working from Hull and Grimsby were sailing smacks, and these beautiful and seaworthy craft crowded the Humber. Bigger sailing ships kept them company, but now the days of sail are almost gone.

In the sailing days Grimsby’s great advantage was being nearer the sea than Hull. Moreover, the situation of Grimsby made it a desirable storing-

THE NORTH BANK OF THE RIVER HUMBER is lined at Hull with the docks and quay walls of the port. There are ten docks in the system, and they cover a total water area of about 203 acres. The river frontage extends for about seven miles. Riverside Quay has a length of 2,500 feet and varies in width Between 85 and 150 .eet. Here is handled the passenger and cargo traffic of the railway-

In the sailing days the Grimsby cod-

To-

To clear the hundreds of tons of fish that are landed each weekday — 600, 700, 800 and more tons a day are regular happenings — thorough organization and expedition are necessary. The London and North Eastern Railway is largely responsible for coping with this matter, and it does so with a system of special fish expresses.

At stated times these fish trains leave and they are as carefully scheduled as the most famous passenger expresses, for it is imperative that the London and provincial markets shall receive the fish without delay. The town’s advantageous geographical position and the service of the daily express fish trains to all parts of the kingdom make Grimsby, it is claimed, the finest distributing centre in Great Britain.

The new Fish Dock, the cost of which has been about £1,700,000, has relieved the pressure considerably and, with its water area of 35 acres, it is invaluable for the repair and coaling of fishing craft. Two coaling jetties are provided and six trawlers can be coaled at once by belt appliances fed from the shore. As trawlers must be coaled quickly these facilities are of the greatest importance. Slipways are provided which will accommodate no fewer than ten vessels at one time for repairs.

The original estimate for the new Fish Dock was £1,418,000, but additions and extensive alterations in designs, due to the difficulties which arose, increased the expenditure by nearly £300,000. As the Grimsby Corporation was tobe mainly responsible for the building of the dock the Government sanctioned a grant towards the interest payment on the loan, with the excellent object of helping unemployment in Grimsby and the depressed areas.

The new Fish Dock has been built on the foreshore, to the east of the existing docks, and by adding the water area of 35 acres brings the total area of the fish docks to 64 acres. But the new dock area is only a part of the total area of 175 acres enclosed by the new river embankment, the reclaimed land being needed for additional general and coal sidings and for industrial development.

Although the fishing dominates Grimsby there is carried on continuously the general trade which adds so much interest to the town. As that trade develops old jetties and other structures are demolished, the railway arrangements are being greatly improved, and better facilities are being provided to deal with the heavy coal exports and the important traffic in timber, wood pulp, pig iron, iron ore and so on.

The transit sheds on the east side of the Royal Dock are specially adapted to deal with import traffic, and on the west side there is a magnificent shed covering 160,200 square feet, one of the finest of its kind in England, and used solely for export traffic. Near by are splendidly fitted wool, cotton, grain, bonded and other warehouses.

The business possibilities of Hull and Grimsby were realized long ago, and the rapid growth and prosperity of these two ports are proof of the foresight and courage of individuals and the powerful help of such a corporate body as the London and North Eastern Railway Company.

Both these ports owe much to judicious reclamation. The work of reclamation indicates how clearly these who are responsible for the welfare of their respective ports have taken advantage of natural opportunities. Such a task has involved heavy expenditure, and in many instances unexpected difficulties have had to be met and overcome. In view of the enterprise constantly shown by the local authorities of the two great Humber ports, it is easy to understand the progress made by Hull and Grimsby during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

THE PORT OF GRIMSBY is largely devoted to the fishing industry. The dock system has an area of nearly 140 acres of deep water, and the quays extend for a length of more than 27,000 feet. The Royal Dock was opened in 1852, and two years later Fish Dock No. I was built. Fish Dock No. 3 was begun in 1930.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “Deep Sea Fishing”, “Fishery Protection” and “The White Pioneer” on this website.