© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Discovery of America

In the face of almost universal opposition Christopher Columbus and his small expedition set out across the unknown waters of the Atlantic Ocean in search of a new route to the continent of Asia

SUPREME FEATS OF NAVIGATION -

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS was the only early navigator or explorer who altered the whole course of history by the achievements of a single voyage.

CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS was the only early navigator or explorer who altered the whole course of history by the achievements of a single voyage.

Although he set out across the unknown waters of the Atlantic Ocean with the intention of opening up a new route to Asia, he discovered the New World, the great American continent. Christopher Columbus gave new life to the Old World.

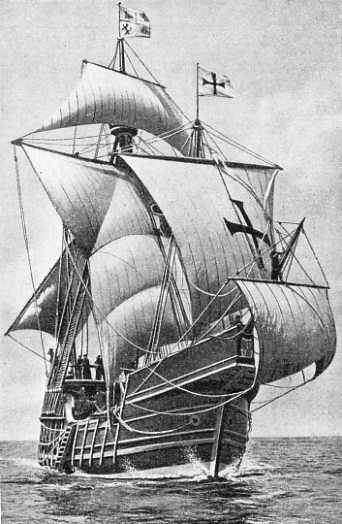

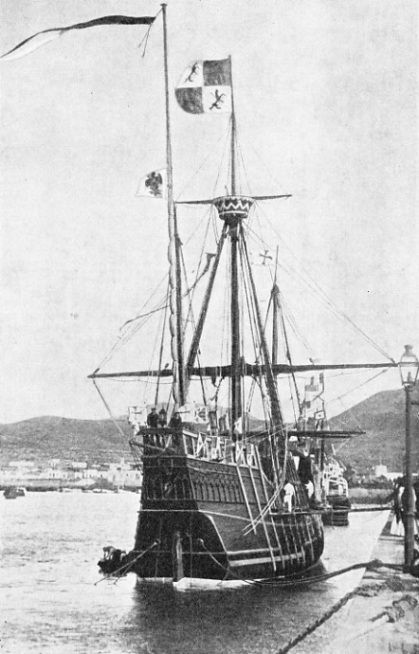

THE CARAVEL in which Columbus first sailed across the Atlantic was called the Santa Maria. This illustration shows the general design of the caravel. She was a vessel of 100 tons burden, the largest in the expedition. Her foremast and mainmast were square-

The map of the world in the middle of the fifteenth century was limited to the continents of Asia Africa and Europe.

Martin Behaim of Nurnberg, a contemporary of Columbus, converted the astrolabe, an astronomical instrument, for the use of mariners. According to Behaim, it was possible to run down to the latitude of the Canary Islands and then sail directly west as far as Cipango, as Japan was then called. The distance was unknown, the seas perilous, and it was considered more than foolhardy to make the attempt. The Portuguese navigators had discovered the comparatively safe coastwise route, and only a man with the patience and determination of Christopher Columbus would have attempted the dangerous exploration in the face of universal opposition.

From his earliest boyhood Columbus felt the sea-

The sea must have inspired him with high ambitions, for when his father gave up his trade and moved to Savona, farther along the coast, Christopher decided to go to Lisbon, the home port of the Portuguese navigators. At this time he was twenty-

He submitted his plans to King John II of Portugal. Four authorities were appointed to give them full consideration. The Bishop of Ceuta, however, suggested that a refusal should be sent to Columbus himself, but that a ship should secretly be dispatched in accordance with the suggestions of Columbus to test his theory. This vessel was forced back by storms, and news of the subterfuge reached Columbus.

Columbus realized that nothing further could be achieved in Lisbon and he decided to leave Portugal. He set out for Spain and transferred his activities to Seville. Here he soon found friends among men of learning, and on one occasion he was presented to Queen Isabella at Corboba. The Queen thought so much of his project that she appointed a committee to submit an opinion.

This committee rejected the proposals, and Columbus was downcast by the decision. He was befriended, however, by Diego de Deza, the Prior of San Estevan, and Columbus continued the discussion of his plans with monks, professors and courtiers. Ferdinand and Isabella heard of these discussions and summoned Columbus to their court. Isabella promised her personal attention, but after years had passed without result, Columbus decided to apply elsewhere for patronage.

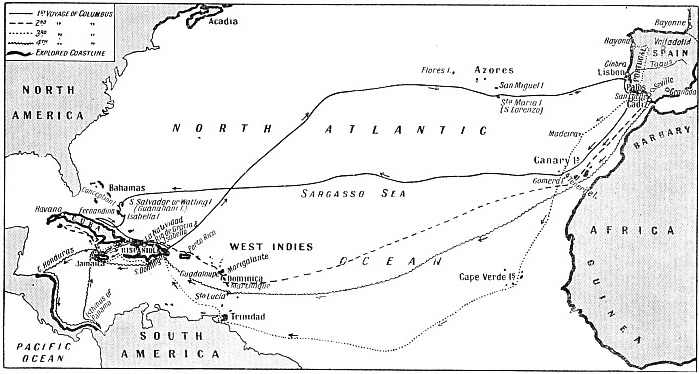

THE ATLANTIC OCEAN had never been crossed before Columbus sailed from Spain in 1492, although Vikings had crossed to Greenland. His first voyage took him through the Sargasso Sea, and he first sighted land at the island of San Salvador. He landed on Hispaniola, now known as Haiti, and established a settlement at La Natividad. On the return voyage the vessels were driven to San Lorenzo in the Azores for shelter. Three further voyages of exploration were made by Columbus, but as on each occasion he returned on a straight course for Spain, the homebound routes are not shown on this map, to facilitate the illustration of his outward voyages.

He sent his brother, Bartolome, to negotiate with Henry VII of England. Bartolome met with no success, and Christopher, his patience sorely tried, decided to join his brother and try to persuade the French court to sponsor his scheme. He had begun the journey when a message from Queen Isabella reached him. He turned back, and was given an audience with the Queen. His plans had been accepted.

After some delay, the expedition was fitted out. The Santa Maria, the biggest vessel, was about 100 tons burden, and her complement, including Columbus himself, was fifty-

Martin Alonzo Pinzon commanded the caravel Pinta, of about fifty tons. This vessel was at the time lateen-

The. third vessel, a caravel of forty tons, was the Nina. She was owned by the Nino family of Palos and carried a crew of eighteen under the command of Vicente Yanez Pinzon, brother of the Pinta’s captain. There were thus eighty-

On August 12, however, the peak of Tenerife was sighted. In the Canary Islands Columbus and the Pinzon brothers superintended the repairs of the Pinta. The repairs were completed, and square-

Discontent Among the Crews

The three vessels left the island of Gomera on September 6. They drifted in a dead calm for about two days before a breeze enabled them to steer for the unknown west. Gradually the peak of Tenerife vanished in the distance, and the three little vessels were out into the “Green Sea of Darkness”, as the Arabs called the unexplored Atlantic.

The trials of Columbus were many. He continually had to allay the fears of the crews. They became frightened at the appearance of weed as they approached what is now called the Sargasso Sea. They feared that the dense masses of weed would bring them to a standstill and that they would die of hunger and thirst. Columbus suggested reasons why this would not be so, but before long the constancy of the wind renewed the alarm of the sailors. They thought it would never change and that the ships would be unable to return to Spain. Fortunately a fresh breeze sprang up from the south-

As the days wore on and no land appeared, Columbus consulted Martin Pinzon and passed Toscanelli’s chart to him along a line stretched between their respective ships. They agreed that their position was near an island named Antilla in the middle of the ocean, and at sunset on the same day Pinzon shouted that he saw land. The crews climbed the rigging of all three ships and confirmed his statement. When day dawned they found they had been deceived by the shape of clouds on the horizon. A week went by without any sight of land and the crew began to urge Columbus to alter course to the southwest. Columbus noticed that flocks of birds were passing continually towards the south-

When the ships had sailed on the new course for four days and there was still no sign of land, the men began to grumble in earnest. They approached Columbus and told him that they had sailed far enough. He exercised his authority as the captain-

At about ten o’clock that night Columbus was watching from the high poop of the flagship and saw the flicker of a light on the horizon. The light vanished. Clouds covered the moon and the wind was fresh. The watch was being changed at 2 o’clock on the morning of October 12 when a gun flashed from the Pinta to announce that she had sighted land. The moon, emerging from the clouds, had shone on sandhills only a few miles ahead. The ships were quickly hove-

It is generally accepted that this island was San Salvador, or Watling Island, one of the Bahamas. On the morning of October 12, 1492, Columbus, who, by virtue of the discovery, was no longer a temporary captain-

Discovery of Tobacco

When the adventurers had returned to their vessels the natives swam out and bartered parrots, balls of cotton thread and javelins, for beads and hawk-

Seven natives were taken to act as interpreters as soon as they had learned Spanish. Columbus then sailed to another island, visible to the west. This island he called Conception. Later he overhauled a solitary savage paddling towards the horizon to carry to

another island the news of the white strangers’ appearance. Columbus took the native on board and soon reached an island now identified as Exuma. He called it Fernandina. The next island, now Isla Larga, he called Isabella.

The natives made him understand that to the south was a land called Cuba, and Columbus believed that this was Japan. When the three ships arrived at Cuba, Columbus sent two of his men with two natives in search of the king. The men noticed natives carrying a “burning stick” and some hitherto unknown type of dried leaves. Thus the use of tobacco became known to Europeans.

While off the coast of Cuba, Martin Pinzon, in the Pinta, the fastest of the three vessels, deserted Columbus. Jealousy of his commander made him over-

On the morning of Christmas Eve the two ships weighed anchor, but the wind failed and they were becalmed at sunset. Columbus handed over the helm to the master of the Santa Maria. The master thought that as the night was so calm he could disobey orders and get some sleep. He told a young sailor to take the helm. Before midnight the Santa Maria was aground. Columbus was on deck in a moment and ordered the master to take a boat and lay an anchor astern to haul the vessel off. The master made a second mistake by rowing to the Nina and appealing for help. Vicente Pinzon ordered him back and turned the Nina to the aid of Columbus. The opportunity of saving the Santa Maria, however, was lost. Columbus cut the mast away and heaved cannon and gear overboard in an effort to save his ship, but she drove up to the bank and he was forced to abandon her and take refuge in the Nina.

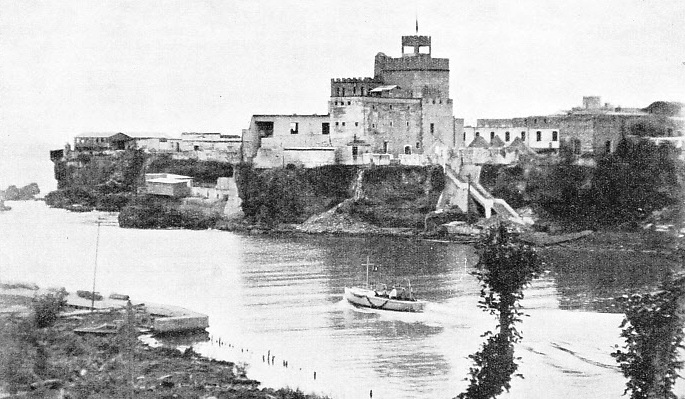

THE FORT AT SAN DOMINGO in the island of Haiti (formerly Hispaniola), was built a few years after Christopher Columbus had been arrested in the town. Columbus built a similar fort at La Natividad on the other side of the island. The settlers there had sent complaints to King Ferdinand of Spain, who had never regarded Columbus with much favour; the King sent Francisco Bobadelia to San Domingo. When Columbus landed there in 1500 he was wrongfully arrested.

Columbus transferred his flag to the Nina, whose captain was Vicente Pinzon, brother of the man who had deserted Columbus. By this quick stroke Columbus showed himself master of the situation.

Canoes besieged the ship, and the Indians offered gold in exchange for hawk-

Many of the sailors wished to remain on the island, and Columbus decided to build a fort and to leave them to discover where the gold came from while he sailed home with the news. The work was put in hand and the fort was built.

News came that the Pinta was somewhere to the east, but she did not return, and by January 4 Columbus was ready to sail. Forty-

Two days after the Nina had left La Natividad, homeward bound, the Pinta was sighted. Martin Pinzon explained that the Pinta had been blown out of sight of the other two ships; but Columbus did not believe this tale, though he concealed his feelings as best he could.

Relations between the leader and his lieutenant were by no means cordial. When they reached a river that Pinzon had previously named after himself, Columbus refused to recognize this name and called the river the Rio de Gracia, or River of Thanks. The first skirmish between the Spaniards and the natives in the New World occurred some days later at another anchorage. A boat had been sent ashore to barter, but the natives became alarmed and appeared to be about to attack. The sailors charged them and wounded two, but next day the natives seemed to have forgotten the encounter and were amicable.

Relations between the leader and his lieutenant were by no means cordial. When they reached a river that Pinzon had previously named after himself, Columbus refused to recognize this name and called the river the Rio de Gracia, or River of Thanks. The first skirmish between the Spaniards and the natives in the New World occurred some days later at another anchorage. A boat had been sent ashore to barter, but the natives became alarmed and appeared to be about to attack. The sailors charged them and wounded two, but next day the natives seemed to have forgotten the encounter and were amicable.

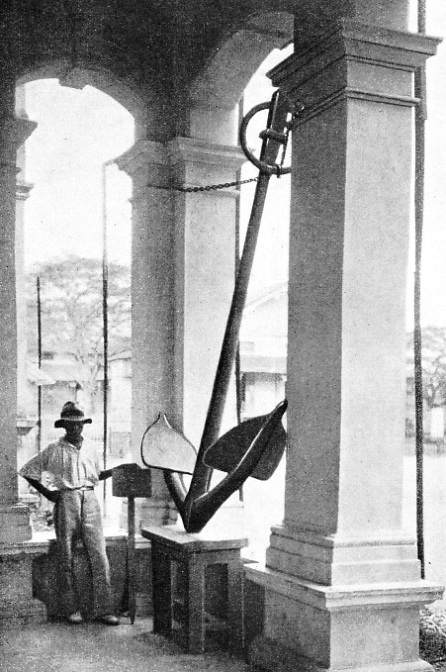

THE ANCHOR LOST BY COLUMBUS off the south coast of Trinidad in August, 1498. Columbus recorded this loss in his journal, and in 1877 the anchor was found in shallow water in the position described by him. The anchor was displayed at the Wembley (Middlesex) Exhibition in 1924, and is now at Port of Spain, a town on the northern coast of Trinidad in British West Indies.

On January 15 Columbus sailed from Hispaniola, intending to make for Porto Rico, but the wind was favourable for the voyage home and the pilots urged him to take the opportunity. The ships were leaky, stores were low, and the men were eager for Spain. Columbus, therefore, gave the order and the two vessels headed for distant Spain. Their luck with the winds held for a week when variable winds set in. The Pinta was in a worse condition than the Nina, and often Columbus had to shorten sail to wait for his lieutenant. On February 3 the wind steadied in their favour and progress improved, but all the estimates of the pilots as to their position differed.

Columbus reckoned that they were in the latitude of Flores Island, in the Azores, and the pilots accepted this as correct. Columbus had noted on the outward voyage the position where the first seaweed of the Sargasso Sea had been sighted, and he based his estimate on the fact that they had recently passed the last of the weed.

The first of many storms struck them on February 12. So bad was the cross-

Columbus retired to his cabin and wrote a brief account of his voyage on a sheet of parchment, with a request that whoever found it should send it to the King and Queen of Spain. The parchment was wrapped in a waxed cloth, placed in a cask and dropped over-

Towards nightfall the wind began to ease, and in the morning the sea had gone down considerably. To the joy of all, land was sighted. The men did not know what land it was, but Columbus surmised it was one of the Azores Islands. The next morning, however, fog enshrouded the ship, and all that day and the following night the vessel beat about while the men again searched for land. Land was sighted next morning, February 17, but it was night before they were able to get near the shore and anchor. Soon afterwards the cable parted and they had to put to sea again. In the morning Columbus sent a boat ashore, and the men were told that the island was Santa Maria, one of the Azores group, and that they would find a good harbour at San Lorenzo, not far distant. Columbus reached San Lorenzo after sunset and found that word had been sent of his arrival.

The men Columbus sent ashore were taken to the Governor, at a town some miles away. Some of the Spaniards returned to the Nina and said that three men had been invited to stay the night with the Governor, who would visit the ship on the morrow. When morning came, Columbus sent more men ashore in two parties to give thanks at the church for their deliverance. Columbus himself waited on board the Nina with the second party until the first party should return. Hours passed, however, and Columbus decided to investigate. He hailed a passing boat and was told that as he had sailed an armed vessel into a Portuguese harbour the men who had landed were under arrest. Columbus threatened to sail to Spain for reinforcements and after much argument he succeeded in rescuing his shore party. It was learnt afterwards that orders had been sent from Portugal to the effect that Columbus should be arrested.

The wind was fair for Spain, and Columbus decided to head straight for home. For the first three days the wind held, but it developed into a. gale. On March 3 a terrific blast blew all the sails to shreds. Next morning the crews found themselves off the Rock of Cintra, on the coast of Portugal. After his experiences at San Lorenzo, Columbus had no desire to seek refuge in Portugal, but there was no alternative. A scrap of sail was patched up and set, and the Nina battled her way towards the River Tagus and anchored in sheltered water off Cascaes. On the flood tide she went up river to Rastelo, near Lisbon, where all vessels had to bring up before receiving permission to proceed to the capital. This was on March 4, 1493.

A FULL-

Columbus was now in the lions’ den. He was in the hands of the nation he had for so long importuned to equip him with ships for his voyage. This voyage was now accomplished, but in the interests of a rival nation. He promptly sent a letter to the King of Portugal asking permission to take his ship to Lisbon, and stating that he had not trespassed in the countries claimed by Portugal, but had voyaged to the Indies by way of the Atlantic. He wrote this letter as an officer of the Spanish Crown.

Columbus was sent for by King John II. Although Columbus believed that he had voyaged to the Indies and the mainland of Asia, he knew that Portugal claimed the Indies as her own territory. King John, however, treated Columbus with courtesy. He offered to have the Admiral escorted to the frontier so that he could go overland to Spain, but Columbus preferred to have the Nina patched up and sail in her to Palos.

She anchored in the mouth of the River Tinto, off Palos, at noon on March 15, 1493, after a voyage of seven months and twelve days. Soon after her the Pinta arrived, to the amazement of all aboard the Nina.

A Hundred Stowaways

The Pinta had reached either Bayonne, on the coast of France, or Bayona, on the coast of Galicia, Spain. Martin Pinzon had sent a message to the King and Queen of Spain claiming the credit for the discovery of the Indies. When his vessel reached Palos and he saw the Nina, therefore, he avoided Columbus and was rowed ashore. He died a little later, without having had any further contact with his admiral.

The mistake Columbus made in believing that he was in Asiatic waters, when he was to the east of an unknown continent thousands of miles away from Asia, was due to his faith in Toscanelli’s map -

The return of Columbus to Spain created an immediate enthusiasm. Hundreds of young men in Spain wanted to ship with Columbus. The admiral was sent to Cadiz to pick his fleet for the next voyage. He chose three ships and fourteen caravels. More than 1,400 men embarked on the second voyage, and when the ships were at sea a hundred stowaways crawled out of their hiding-

Although Columbus had arrived at Palos only on March 15, 1493, he sailed from Cadiz on September 24 for his second voyage. His flagship was the Marigalante, of 400 tons. On November 3 he sighted an island which he called Dominica, now a British possession in the West Indies. He landed on a small island to the north. He called this island Marigalante, and went on to Guadaloupe, where pineapples were discovered.

He reached the settlement at La Natividad, Hispaniola, on November 27, and fired guns to announce his arrival. He waited for the answering salute, but there was only the silence of death. Not a Spaniard remained alive. A new colony was founded on Hispaniola and called Isabella.

On April 24, 1494, Columbus hoisted his flag in the little Nina, and with two other caravels sailed from Isabella, Hispaniola. He discovered the island of Jamaica and revisited Cuba. He returned to Isabella on September 29, 1494, but he was almost at the point of death. For months he was nursed by his brothers. After his recovery he returned to Spain and reached Cadiz on June 11, 1496.

His third voyage started on May 30, 1498. Trinidad was discovered on July 31, and a landing was made next day. From Trinidad Columbus saw in the distance the mainland of South America, but at first thought it was yet another island. It was not until some time later that he decided it must be the continent of Asia. He did not realize that Cuba was an island but thought it a long promontory of the mainland.

Every ship which returned to Spain brought home colonists with grumbles and complaints. These complaints were conveyed to the King and Queen, who selected Francisco Bobadilla and sent him out to take over the command. He arrived in San Domingo, part of the island of Hispaniola, in August 1500. When Columbus returned he was arrested and placed in irons.

He reached Cadiz in November 1500. The news spread through the country and aroused the utmost indignation. The captive was freed immediately, and Bobadilla, who had greatly exceeded his orders, was recalled. Full restitution was promised to Columbus.

Disaster From a Hurricane

He sailed again from Cadiz in May 1503, with four vessels and reached an island, probably St. Lucia, in June. Although he had been ordered not to touch at San Domingo, he was compelled to do so because of the condition of one vessel. Ovando, who had been sent to supersede Bobadilla, ordered him off. Columbus obeyed, but not before he had sent a warning to Ovando advising him to detain the Spanish fleet in harbour because a storm was approaching. Ovando ignored the warning, and more than twenty of his thirty-

The great sailor discovered Honduras and cruised along the isthmus of Panama. The ships became riddled with teredo worms, and at last Columbus was obliged to run his two remaining ships on a beach in Jamaica to prevent them from sinking. The sailors lived in huts on the beached ships’ decks while news of their plight was sent to Ovando.

At last help was sent to Columbus from San Domingo. He was a sick man when he reached Seville in November 1504, to find that his friend the Queen was dead.

Columbus was unable to get to court until the following May, and found that the King was indefinite about the restitution of his rights. A doomed man, Columbus survived until May 20, 1506, when he died at Valladolid in Northern Spain.

Columbus never realized that he had not sailed in Asiatic waters. He died in the knowledge that he had achieved a remarkable feat of navigation and that he had opened up rich new lands for the profit of his patrons. Not for many years could the value of his discoveries be fully appreciated. The greatest and most determined of all pioneers, Christopher Columbus did more than any other man can ever hope now to do -

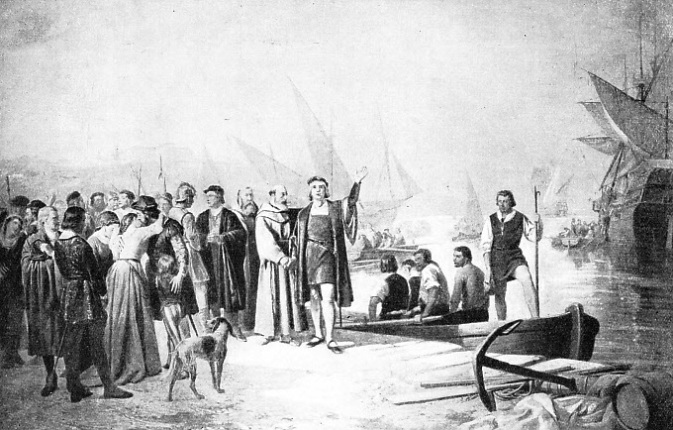

COLUMBUS LEAVING THE OLD WORLD on the famous voyage which discovered the New. This illustration is an impression by the artist Balaca of the scene at La Rabida as the expedition embarked. La Rabida is a short distance downstream from the port of Palos at the mouth of the River Tinto on the southeastern coast of Spain, from which the expedition set out for the unknown.

You can read more on “Epics of Exploration”, “Great Voyages in Little Ships” and

“Supreme Feats of Navigation” on this website.