© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

His Majesty’s Customs Service

The origin and growth of the unobtrusive but efficient Customs Service make a story full of romance. To-

THE CUSTOM HOUSE IN LONDON is situated on the north bank of the River Thames, just below London Bridge. Built in 1814, the Custom House is an imposing building set on a wide quay. The Long Room is 190 feet long, 66 feet broad and 55 feet high. In the background of the photograph, behind the left wing of the Custom House may be seen the Monument. Farther to the left is the dome of St. Paul’s. In the left foreground is the Torras y Bages, a Spanish vessel of 1,344 tons gross.

PROBABLY less is known about the Customs Service than about any other service connected with the sea. Often the Customs officials would prefer to have it that way, for it permits them to carry out their duties undisturbed.

To the layman the Customs officer is only the man who makes an apparently cursory examination of the baggage brought ashore by the passenger from the ship and who discovers, or occasionally does not discover, the bottle of scent which is to be a present for Aunt Maud or the cigars for Uncle William.

The duties of the Custom House officer are infinitely wider than this. Some of them are exceedingly interesting and often most exciting; some of them are purely routine. Exciting or not, they are all carried out with extraordinarily smooth efficiency by quiet-

The first imposition of customs is lost in the mists of history; their very name as “payment according to ancient custom” is an indication, but there is every evidence that the Romans imposed some form of import customs duty on the Britons during the occupation. It is difficult to imagine any early king or chief who would allow traders to operate within his area without special permission, and this permission would certainly have to be paid for. This applied to goods exported as well as imported. The first definite information we have goes back to the year 979 when the witenagemot (parliament) under King Ethelred laid down a schedule which covered not only cargoes but also what would now be regarded as port dues. William the Conqueror appears to have levied heavy Customs taxes, paid in kind and not in cash, but it was Henry II who put things on a more regular basis. He kept proper records for the first time and farmed out the revenue to speculators and courtiers. The farmer selected would pay the King a certain set sum every year and would then make as much profit as he could out of the merchants under the schedules laid down. The trader was generally victimized and had to pay not only the farmer but also numerous officials who had their perquisites.

The Lieutenant of the Tower took his full toll of a ship’s cargo before she was allowed to pass the fortress to the quays of London, and the King’s butler had the right to examine all wine cargoes and take away the best at a nominal price. This was legally for the King’s use only, but the butler favoured his friends, and the King himself often set up as a cut-

Customs payments in kind were known as prisage (“rightful prisage” and “evil prisage”). In cash there was often a temporary tax known as “maltolte”, and nearly all exports and certain imports were paid according to “ancient custom”.

When the receipts were farmed out for a fixed annual sum the Crown was naturally indifferent as to how the farmers collected them. Often the farming of all or part of the Customs was let out to foreigners, sometimes to the Hanseatic merchants of the Steelyard and sometimes to the Italian usurers, who so often had the King of England in their debt.

These foreign farmers were invariably unpopular and were noted as being harsh and grasping, far worse than the King’s favourites, who were apt to be easy-

The exports of the country, particularly wool, yielded most revenue for many years, but the import duty on wine was valuable from Saxon days.

“Sufferance Wharves”

Heavy duties on the spices brought from the East in large quantities yielded valuable revenue. These duties were used as an excuse to force up the price, and in 1309 Parliament suddenly ordered the abolition of all duties on wines, broadcloths and other useful commodities as an experiment. As the free entry did not result in the slightest reduction in price the duties were quickly reimposed.

The rapid expansion of English trade under the Tudors led to many developments in the Customs which were continued under the Stuarts. Queen Elizabeth, with her shrewdness in money matters, made great improvements. She took good care that the Crown got its full share of the benefits of increasing trade. In the early days of her reign the revenue was farmed to Sir T. Smith, Secretary of State, for £14,000, but before her death the price had been increased to £50,000.

To prevent goods from being slipped ashore without payment she made it a penal offence to land foreign cargo in London anywhere but at the “legal quays” on the north side of the Pool. As the trade of London grew these legal quays became inadequate and “sufferance wharves” were added, at which goods might be landed on sufferance by special payment. Legal quays and sufferance wharves still exist to-

H.M. CUSTOMS AND EXCISE CUTTER, ENTERPRISE, one of the large modern fleet, is stationed at Gravesend on the River Thames. These vessels carry parties, known as rummage crews, which board incoming vessels and search for contraband. In an amazingly brief time they can detect contraband smuggled in the most ingenious hiding-

Charles I made business easier by permitting bonds to be accepted from consignees who had difficulty in finding cash until their goods were sold, but he often had to mortgage his Customs revenues to the financiers just as he had to pawn his jewellery. Charles II was shrewd enough to get money by thoroughly reorganizing the Customs in 1671, setting up a Board of Commissioners and taking a definite step towards the abolition of the farming system.

These reforms were a move in the right direction, but they did not go far. Most of the trouble was in the appointments. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the senior revenue officers received no salary at all, but were expected to reimburse themselves from an elaborate scale of fees, the majority unauthorized by Parliament, and from arbitrary fines inflicted on merchants. These and other posts were awarded by favour, largely in return for political services, and the holders looked after themselves. In 1774 it was discovered that out of sixty revenue appointments made directly from the Crown, fifty-

Yet the receipts from the Customs were becoming more and more important to the country. A new scale was introduced at the end of the seventeenth century to pay for William III’s wars and social legislation. Duties went up and smuggling immediately became a carefully organized business. It had existed from time immemorial, at first in the form of “owling” or smuggling wool out of the country against Royal prohibition. As the scale of duties rose and more elaborate arrangements were made, so smuggling became really scientific and its golden age started. A full account of smuggling at this period is given in the chapter beginning on page 859.

The smugglers were often quite open in their operations. For most of the time the regular King’s forces were engaged fighting his enemies and the protection of the revenue was left to those for whom the Services had no further use. Many of these men accepted bribes and nearly all were influenced more by intense jealousy of their colleagues than by their duty to the King and country.

The whole system was wrong. The regulations were so complicated that nobody could possibly understand them, and they offered every chance of victimization. The price of everything subject to duty went up and the public was too poor to buy the articles legitimately imported. The law was so contradictory that keen officers had the chagrin of seeing smuggled goods, once having come to rest, openly advertised as such in the shops.

The “Starving and Burning Act”

William Pitt had more liberal ideas of the way in which trade should be encouraged. In 1787 he concluded a treaty with France and reduced the tariffs on most goods. His measure was most unpopular with the smugglers themselves, who called it the “Starving and Burning Act”, and maintained that it was intended to kill them. The Channel Islands, which had their own local government and fiscal power, ordered their forts, flying the British flag, to fire on any British cruiser which dared to chase a smuggler within British territorial limits. They even presented a petition to Parliament pointing out how much more advantageous it was to the country to have British smugglers instead of French.

Ever since the middle of the seventeenth century the Customs authorities had maintained not only a land force but also a number of boats. When William III increased the tariff schedule he secured a number of big smacks, all reputed to be fast sailers, and armed them to run down smugglers.

The smacks were generally taken up with their crews complete, only one Customs officer shipping with them when there was work to be done. Ashore, however, there were surveyors, land waiters, tide waiters, coast waiters, boatmen, riding surveyors and many other ratings. The Navy helped them to destroy such smugglers as they encountered in their duty afloat, and in return the Customs helped the Navy with the Press Gang. Small men-

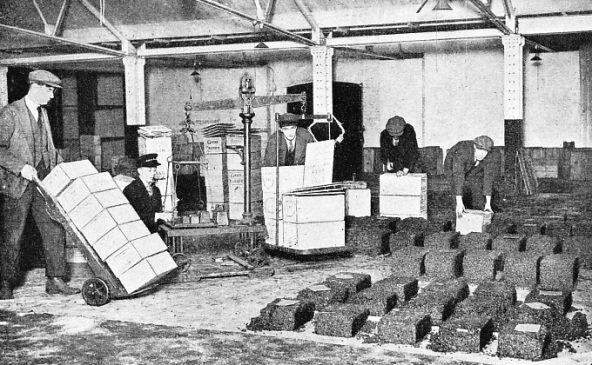

A LARGE CONSIGNMENT OF CURRANTS AND SULTANAS being weighed at the London Docks. This consignment was brought from Greece by the Livorno, 1,829 tons gross. The fruit is tipped out of the boxes and packing cases because they do not have to be weighed. This is also a precaution against goods carrying a heavy duty being concealed in goods on which a light duty is paid.

When things got worse and worse during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars the Customs service was made more elaborate. The preventive waterguard was established to work with the landguard. Generous rewards were offered for captured contraband and smugglers who could be passed into the naval service, where their seamanship was fully appreciated. Despite this, the great change was not made until after the battle of Waterloo.

As happens after the end of every important war, the Admiralty of 1815 was faced with the problem of what to do with the surplus men. Ships were being paid off as fast as they could be dismantled, but to send the crews ashore with no better provision than a permit to beg without being gaoled was cruel. Also, the Admiralty wanted to keep its hands on the best-

Captain M’Culloch had the excellent idea of offering the revenue authorities full naval help to check smuggling. The English coast which offered the smugglers the best opportunity, was to be blockaded as closely as the French coast had been during the war. The Customs should foot the bill, but the Navy would supply far better men and material than the Customs could hope for.

The plan was a success from the first and from the Coast Blockade grew the Coastguard, under which the Navy supplied the disciplined men and maintained them in stations all round the coast, co-

When the Crimean War broke out in 1854 the men were all called up and the Customs objected that they had been paying generously for all those years and just when the men were wanted most they were all drafted into the fleet and not a single man was left. So the Admiralty shouldered the cost and lent its services to the Customs.

Chaotic System of Fees

Shortly before the war of 1914-

The first half of the nineteenth century made all the difference to the Customs Service. It removed its abuses, lightened its work and, curiously enough, made it infinitely more profitable for everybody. The change began in 1831 when all Customs fees were abolished and the officers were paid compensation for what they were losing.

This system of fees had grown up in an appalling manner and nobody knew which were sanctioned by law, in substitution for a proper salary, and which had been invented by ingenious officials. They had become such a fixed institution that the officers who relied upon them for their living had to be compensated. The authorities instructed every clerk and officer to report the fees that he was receiving, and as the rumour spread that the inquiries were for taxation purposes, the majority of the returns and the consequent sums paid in compensation were low. It was proved that officers rated at £60 a year were receiving £1,000 a year in fees, and clerks at £100 salary were getting £2,400 and more.

Then, in the ‘forties, Sir Robert Peel carried out a great reduction in the list of dutiable articles, starting a policy which went on for some years afterwards. As smuggling was no longer worth while, it died a natural death except for the smuggling of the few articles which were kept on the schedule. In 1787 there were as many as 1,425 articles scheduled and they produced about £6,000,000 in revenue. In 1882 there were only twelve items but they realized £19,000,000. These items were beer, cards, chicory, coffee, cocoa, dried fruit, malt, lace, spirits, tea, tobacco and wine.

AT TILBURY the baggage of passengers from incoming liners is examined in a spacious new building. Disembarking passengers enter the Customs Hall, where their baggage, waiting under the initial letter of their name, is carefully scrutinized. From this hall they enter the adjoining railway station.

A certain amount of smuggling still went on, but it was mostly by passengers who wanted the excitement of the game, and it was not on sufficiently large a scale to worry the revenue. The Customs and their allies the Coastguards could keep the trouble within easy proportions with little difficulty, so that it was only natural that many other jobs, in addition to those for which they had been responsible all the time, were piled on to their shoulders. Then came the war in 1914 and everything was changed. Some of the smartest Custom House officers were transferred to the Immigration Department of the Home Office, guarding the country against the entry of undesirable aliens of all kinds. The watch on the ports, and on the exposed parts of the coast, had to be made much closer to prevent enemies from smuggling in communications or articles dangerous to the country. The force was short-

In the latter part of the war, and the years which immediately followed it, a number of fresh articles were made subject to duty to raise revenue. The old Admiralty Coastguard Force had gone, and the Board of Trade force which replaced it had too much of its own work to do to be of any help.

After the war came the slump, with its terrible unemployment, and gradually a new schedule was built up which was not designed to raise revenue nearly as much as to provide employment for the workers. The heavy duty on silk, for instance, was primarily intended to encourage the artificial silk industry in Great Britain, and many other duties were imposed for the same purpose. These duties were more strictly applied than those for revenue purposes only, where a certain amount of good-

The schedule of goods liable to Customs duty became as long as it had been in the eighteenth century, but the administration was different. Everything was correctly regulated and above-

It is a fine compliment to the Custom House of to-

Smartness and Discretion

The average citizen sees little of the work of the department. To most a Customs officer is only a man in an unpretentious uniform who seems to take a casual interest in his baggage and to have extraordinary luck in dropping on any contraband. There is really little luck about the matter. The Customs officer is chosen for his smartness, and retains his job by maintaining his standard. Above everything, he is a practical psychologist with the knack of putting himself in the place of the traveller who wants to bring ashore a few smuggled goods, not so much to defraud the revenue as to have the excitement and to express the age-

As a rule, the officer generally sees far more than he betrays. He is allowed to use much discretion, and where the capture does not really matter, except for his own credit, he will occasionally turn a blind eye rather than delay a boat train. At the same time, he hates it to be thought that he has been bluffed, and a bewildered passenger will often find himself dropped on with surprising weight for this reason.

In addition to his own powers of detection, which are considerable, and the too obvious unconcern of the amateur smuggler, the Custom House officer has the help of many informants who are attracted by the reward paid in the event of detection. Unfortunately, there are no informers about the contraband which is loathed most -

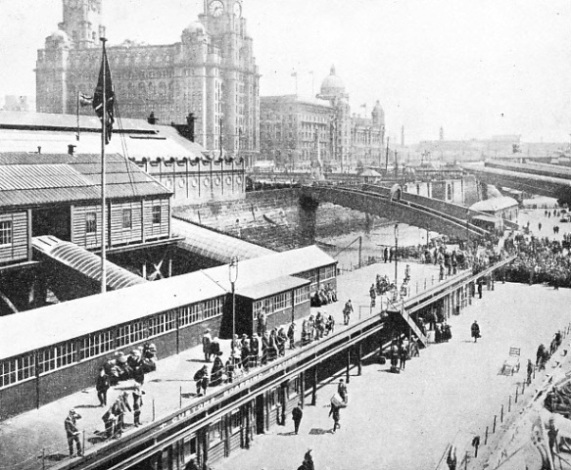

LIVERPOOL LANDING STAGE is one of the most interesting river fronts in Great Britain. Many ocean liners and river craft berth at the floating stage. Passengers ascend to the Customs Department over a bridge, and behind the Customs building is the Riverside Station, for boat-

Smuggling by the passengers of cross-

Akin to the officers who examine the passengers’ baggage at the ports and the railway termini are the boarding and rummage crews of the waterguard. These two branches join almost every ship coming from overseas. The boarding crew examines the ship’s stores, puts any surplus under seal so that it can be used as soon as she leaves British waters, and also does a dozen jobs connected with the legal entry of the ship.

The rummage crew has the more picturesque job -

At every dock or wharf which deals with overseas shipping there are officers who examine every pound of cargo which comes out of the ship’s holds, and who assess the amount of duty payable. This may not be as picturesque a job as, the examination of baggage or the work of the rummage crews, but it has its interesting side. Not only is it difficult to make an exact assessment without delaying the consignment for an unnecessary minute, but also it is an old trick to smuggle heavily dutiable articles concealed in those on which the duty is light.

Plain-

With the small force now at their disposal, and the long line of coast which is left unprotected by the withdrawal of the Coastguard, it is physically impossible to prevent a good deal of contraband coming over the coast-

The detection of smuggling is by far the most romantic and interesting part of the duties of the Customs House officers. The service maintains a number of launches in the various ports and rivers which are seldom used in the prevention of smuggling, although they form a cog in the big machine. The Service has to cover the granting of pratique to ships which might bring in plague or other infectious disease.

It secures the material and prepares the statistics which are necessary for the promotion of trade. It keeps a careful check on the movement of ships, incidentally preventing piracy, by the issue of clearances. It assesses and collects the light dues which permit Trinity House to maintain the lighthouses and navigation marks round the coast. It grants registration, secures masters in their commands, and does a thousand and one jobs which are undreamed-

The Customs Service is now one of the finest under the Crown though, unfortunately, one to which the least credit is given by the general public which benefits so much by its activities.

CUSTOMS OFFICERS EXAMINING MOTOR CARS at Southampton. In certain circumstances a triptyque is issued for visitors’ cars entering or leaving the country. A deposit is paid in lieu of Customs duty, and is refunded if and when the car is returned. Officials examine the cars to check engine numbers and other details on the triptyque, and to see that for the outward voyage the petrol tanks are emptied

You can read more on “Fishery Protection”, “Pilots and Their Work” and

“Smugglers and Revenue Cutters” on this website.