© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The “Araby”: the Ship That Broke Her Back

The British Navy, with 120 ships and thousands of men, blocked the harbour at Ostend. By chance, a German submarine, in attempting to sink the British cargo boat “Araby”, achieved a similar result at Boulogne

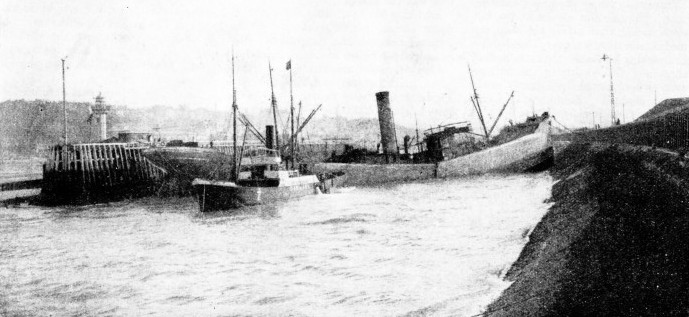

FATE PLAYS A HAND. The British steamer Araby, which in September 1916 unwittingly caused the blocking of Boulogne Harbour. Owned by D. Mclver, Son & Co., Ltd., of Liverpool, she had a gross tonnage of 3,303, was 360 feet long, and had a beam of 48 feet. In escaping from the attack of a German submarine, the vessel ran aground. While tugs were towing her into Boulogne Harbour, the hawsers broke, and the Araby, her steering-

FOR sheer malignancy it would be difficult to beat the fate of the steamer Araby, which set out in September 1916 from Liverpool, to make the long journey of 6,000 miles to Rosario, in the Argentine. Having escaped the attention of the German submarines round the English coast, she arrived safely in the River Plate, where she took on board a cargo of oats that were badly needed in the war zone. She then steamed down the river to make her way back across the South Atlantic to Europe.

After having steamed 12,000 miles to fetch and deliver that cargo of oats, she was within a mile or two of Boulogne, her destination, when her look-

The master of the Araby, seeking to escape, began to draw in nearer to the shore in the hope that the shoaling water would compel the submarine to give up the chase. The grain ship was slow; otherwise she might have gone ahead. As it was, her call for help brought one or two torpedo boats from Boulogne; but, before they could approach near enough to drive off the U-

With as little delay as possible, one or two tugs were told off to refloat the Araby, a task they began to perform as soon as the tide served.

So far as could be seen, she was little the worse for the mishap. Her steering-

Towing her slowly along the coast, the tugs came to Boulogne, where it was intended to berth the Araby in the inner harbour. This compelled them to take her between the two quays that jutted out into the Channel. It was no easy operation, for there was not room for a steamer of her size to turn between the quays. The fact that her steering-

At once the strong tide took hold of her and twisted her round until she was jammed across the harbour mouth, with her bow held fast in the bottom against one quay and her stern all but touching the other. It was about the worst possible thing that could have happened to Boulogne, for the ship completely blocked the inner harbour, making it impossible for any other ship to pass in or out.

The authorities were alarmed, for they saw looming up a disaster which would rob them of vital harbour facilities. They were still struggling with the transport problems of the long-

There were ample grounds for excitement. The tide was almost at the full, which meant that unless the ship was freed at once there was every likelihood of her breaking her back. She was heavily laden, and the bottom of the harbour along either quay shelved deeply to the central channel. So long as enough water remained in the centre to hold her up and keep her afloat she would be safe, but directly the depth of water fell, all support would be withdrawn from the centre of her keel. The keel would thus have to withstand the whole weight of her cargo -

The crews of the tugs, urged on by the excitement all round them, struggled hard to avoid the catastrophe. Making their heavy hawsers fast again, they made every effort to tow at least one end of the Araby free to give the harbour clearance. It was no good. While they worked so energetically, the tide began to ebb. Every minute it dropped lower, leaving the ship more firmly wedged than ever.

Orders, appeals and all the hauling power that the tugs could muster were alike helpless to move that inert mass. The authorities, looking with anxious eyes for the first sign of a break, saw the ship sag slowly till the strain on her keel was too much.

Breaking her back, the Araby settled down at an angle right across the channel between the two quays. She completely blocked the inner harbour.

One German submarine, operating alone, had effectively done for Boulogne Harbour what the British Navy were later to attempt at Ostend, with 120 ships and thousands of men, many of whom lost their lives. The German submarine, in attempting to sink a cargo boat, had succeeded in carrying out the major operation of blocking Boulogne Harbour.

A Drastic Proposal

So desperate a situation called for measures that would brook no delay. Somehow, anyhow, the Araby had to be cleared out of the way at the earliest moment. While the authorities were endeavouring to find a quick method of clearing the port, the gravity of their dilemma compelled them to embrace wholeheartedly a revolutionary scheme advanced by a soldier.

Lieut.-

Lieut.-

One of the first things to be done was to get rid of some of the cargo to lighten the ship. While the men were wrestling with the grain in the holds, the salvage carpenters -

By the time the frames were in place, tons of sand and cement had been carted to the spot. The concrete was well mixed and shovelled and rammed into the moulds. In a day or two it set quite hard, to form two impervious walls that made the bow and stern of the ship water-

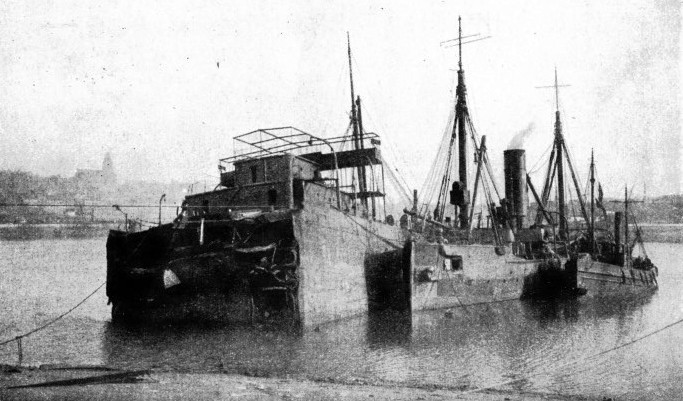

THE ARABY’S BOW beached in Boulogne Harbour. Faced with the urgent need of clearing the harbour of the obstruction caused by the Araby, the authorities adopted a proposal by Lieut.-

While the construction of these concrete bulkheads was going forward, Capt. H. Pomeroy, the able salvage officer who was co-

By dawn on January 11, 1917, the men were busy dropping their pumps into position and screening the mouths so that there was no likelihood of the cargo or anything in the ship choking them. Directly they were in place, Capt. Pomeroy started up the pumps, which were soon pouring cascades of water over the side of the ship. Lieut.-

Waiting for his moment, Capt. Pomeroy, whose towing hawsers were already in place, began carefully to manoeuvre her around until she was parallel with the quay and no longer lying athwart the channel. It took hours of delicate handling to work the ship farther into the harbour, away from the entrance, so that ships could pass in and out. The salvage officer made a strenuous effort to tow her clear of the channel, but he needed all the water he could get to float her, and the falling tide made her touch bottom in the channel again, where she unfortunately still interfered with the traffic.

He had, however, cleared the entrance, and that was a noteworthy gain. With a little luck he would be able to take her still farther in on the next tide.

Dogged by Misfortune

Then the perverse fate which seemed to shadow the Araby once more intervened, She was, as we know, a broken ship. It will be appreciated that the operation of hauling and towing a ship weighing several thousand tons subjected that ship to a vast strain. Under this strain the ominous crack across her keel began to extend and creep up either side of the hull.

The salvage officer became uneasy. Setting the salvage squad to work, he bade them do their best to strengthen her with baulks of timber. He needed only a tide or two to move the ship safely out of the narrow channel to a spot where she could be dealt with at leisure and without interference with the traffic of the busy port.

Forty-

A close examination revealed that the steel plates of her hull were being torn apart as though they were so much brown paper. Her broken keel allowed either end to move independently, and, as the ends moved under the strain of towing, the crack crept across one plate after another until it was half way up the hull.

If only the few remaining plates had held her together a little longer, all would have been well. But the next time an attempt was made to gain a few yards the strain was too much. The thick steel plates were rent asunder. The Araby broke apart and dropped to the bottom.

This calamity would have made most men throw up the sponge. Salvage men become used to hard knocks. If they were inclined to give up when things went against them they would not be able to hold their own in one of the most exacting, disappointing and hazardous professions in the world.

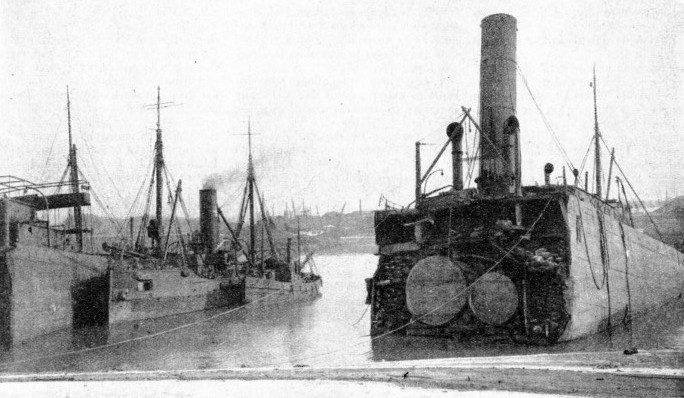

A SALVAGE TRIUMPH. To raise the halves of the Araby from the bottom of the harbour channel, into which they had sunk, large pontoons were used. Two of these were lashed to the bow, pumps were set to work, and gradually the bow was raised. Tide by tide it was slowly moved until it no longer obstructed the harbour traffic, but was beached in the inner harbour. Similar means were used in raising and moving the stern, which is seen in the photograph above. The greater weight of the stern made it more difficult to salve than the bow.

They had to consider what they were to do. Their orders were to get the Araby out of the way as quickly as possible. It might be thought that the speediest way of removing the ends was to blow them to pieces with explosives and to remove the wreckage piecemeal. Capt. Pomeroy was too skilful a salvage officer to do that.

By breaking in halves, the Araby had at any rate solved one of his problems, for he had now no need to worry about what she was going to do, nor was he compelled to handle her as though she were made of glass. The worst had happened. Instead of a whole ship, he had two halves to raise, and his experience had taught him that to lift them entire would take far less time than to cut them to pieces.

In this new emergency he made use of some huge pontoons that were each capable of lifting 800 tons. Lashing two of these pontoons to the bow, he put his pumps to work and felt the bow rising from the bottom. He then lifted the bow out of the way tide by tide until he had managed to beach it in the inner harbour. He performed the same operation with the stern. This gave him much more trouble because it was heavier; but eventually he placed it beside the bow and left the ends there while he hurried off to another job elsewhere. The French Government were so appreciative of his fine work in clearing the harbour that they awarded him the Legion of Honour.

For months the two halves of the Araby lay there on the beach. Nobody paid any attention to them. The sea washed in and out of the open ends, leaving the silt behind. The metal took on a red hue as the rust began to bite into it. If anyone could have picked up those ends and walked off with them, the authorities no doubt would have been only too pleased to look the other way and forget all about it.

The German submarines now became so active that it was absolutely necessary to organize patrols of flying boats and seaplanes. As the strip of beach occupied by the Araby was the only possible landing place that could be used for the purpose, the order went forth to remove the remains of the cargo vessel.

Half-

Once more the salvage men began to scramble about the ends of the broken ship to prepare them for towing to England. The concrete bulkheads built by Lieut.-

The holds, however, still contained large quantities of oats, which it was essential to remove to make the ends of the ship as light as possible. It is a fact well-

Looking down into the hold, one of the salvage crew saw his two comrades stagger and drop. Regardless of his own safety, he lowered himself to the rescue. The gas was so strong that no living creature could withstand it, and he dropped insensible beside the men he was trying to bring out. That was the last touch of the malignant fate which dogged the Araby, for all three men were dead by the time they were brought out.

When the work of preparation was completed towards the middle of July, 1918, the salvage officer set two or three high-

THE ARABY’S BOW AND STERN lay beached in Boulogne Harbour for many months after they had been salvaged. Finally, instructions were given for their removal, as the beach upon which they rested was required as a landing-

You can read more on “Dramas of Salvage”, “The Shipbreaking Industry” and “Ship Surgery” on this website.